Pana was settled by people of European origin, coming from Pennsylvania, Ohio and Kentucky. Some had been born abroad and some were Americans by birth. The town grew and by 1857 was chartered. By 1880 it had 3,000 residents and it grew yet more in the following decade because of the coal mining industry that arose to take advantage of a rich seam.

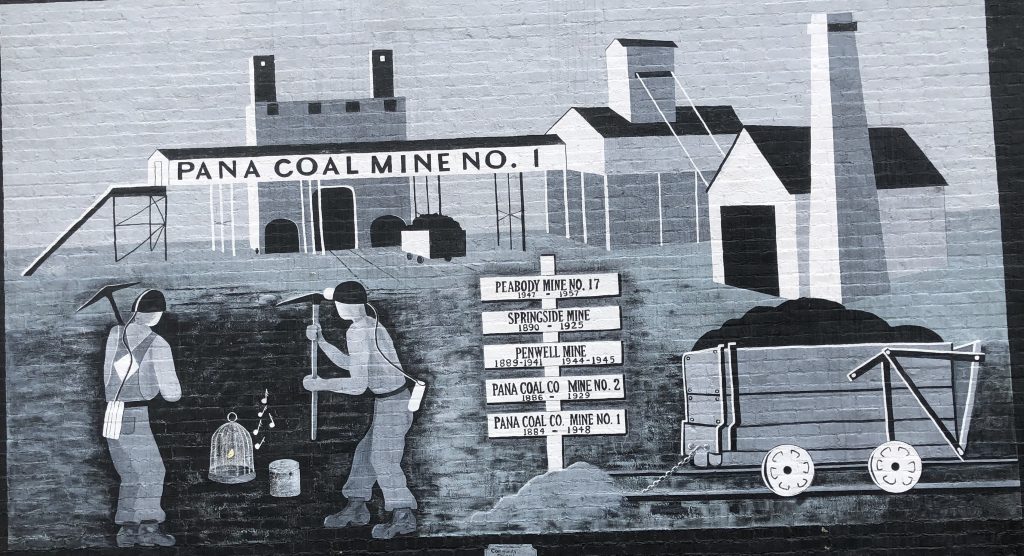

Pana Coal Company Mine No. 1 was, as its name suggests, the first to exploit coal. The need for labor was such that Pana saw a wave of immigration: Irish, Poles, Slavs, French, Germans, and Italians.

More mines were opened and yielded good results. Indeed, mining was booming and it created a need for more housing and for more labor. Miners’ pay was variable but low and, moreover, paid in money and scrip, redeemable at stores. Needless to say, conditions in the mine were poor.

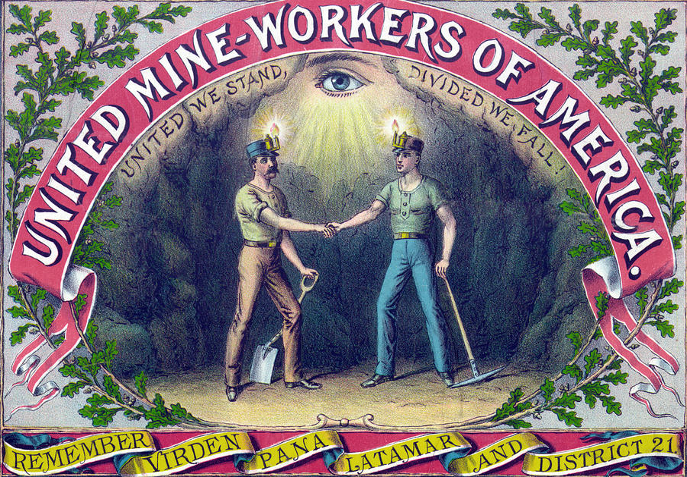

In 1898 Pana miners presented a list of grievances to mine operators, most of which were common in the entire industry. Although the United Mine Workers had been formed in 1890, the Pana miners did not become interested in the union until 1897 when the UMW called a nationwide strike. Coal operators acceded to the UMW demands, particularly wage, at their own choice but Pana and Virden were notable holdouts. Therefore, a second strike began in Pana on April 1, 1898.

Mine operators in Pana did what their fellow capitalists were doing in Virden: seeking cheaper African American labor from Alabama as scabs. Two hundred of them arrived by train on August 24, 1898. As at Virden, the coal operators built a stockade to protect the scabs. And, as at Virden, the scabs claimed to have no knowledge that they were being recruited to break a strike. By October 4, 1898 at least seven hundred African Americans were in Pana, along with their families in many cases. Racial animosity ran high with prejudice furthered by in-group African American behavior regarded as unacceptable by the white population, such as excessive drinking, brawling, and liberal conduct among the black women. Had the scabs been white, they also would not have been welcome by the white striking miners of Pana.

Notwithstanding their poor pay and miserable working conditions, most of the African American miners remained. The white non-mining population was hostile to them as well. Racist language was rife on the street and in newspapers and city meetings.

Striking miners began to capture coal operators. Appeals for state troops were made to Springfield, but without success. As the strike simmered some coal operators mobilized their own armed force, to which the striking miners objected. The mayor closed the saloons. Tensions continued to rise as the UMW sought to legally close the non-compliant mines and African American miners continued to work. Mass encounters began to take place on the street between white and African American miners. Finally, on September 28, 1898 an actual armed battle took place. State troops arrived to try to maintain order. Meanwhile, the “Battle of Virden” was happening on October 12, 1898. In Pana there were more shootings between African Americans and white miners.

Martial law was declared between November 7-21, 1898 but violence on both sides continued in the armed populace, and insults were hurled at the troops. The governor decreed that no weapons could be carried by civilians but this was largely unsuccessful.

The strike continued into 1899 with street violence and legal suits back and forth. The state troops began to be removed in mid-January. Well into March there were fights and deaths, including black on black.

On April 10, 1899 the event known as the Pana Riot broke out, having been boiling into existence for many months. There was general shooting on both sides but the number of dead remains uncertain. The figure is not believed to be large. In addition to African American versus white striking miner violence, businesses were attacked. Many Pana residents are reported to have fled. White union miners organized in squads to look for African Americans fleeing the scene.

READ PROFESSOR’S SUMMARY ARTICLE IN ILLINOIS HERITAGE MAGAZINE:

https://uofi.box.com/s/vaj9a7yo4rhois8o8kxk6tgshnrfxljb

In the end we might conclude that ultimate blame lay with the coal operators who refused to abide by the UMW national wage scale and refused any compromise, seeking instead to use cheaper non-union labor. All sides engaged in violence in those months: the militia of the coal operators, the African American scabs, the white unionized miners.

With the riot over, a scheduled ordinary municipal election occurred in which African American men voted (this was before the Nineteenth Amendment of 1920). The pro-union candidate won. And the last soldiers again left Pana, on June 26, 1899. On October 10, 1899 a settlement between union mines and the coal operators was definitively resolved in favor of the miners.

The reputation of Pana, as a town, was severely damaged by the strike, which was widely reported. People in neighboring towns stopped coming to Pana in fear of violence, whether as individuals or as school members. Moreover, African Americans were driven from Pana, by threat, coercion and inducement. Pana retained a strong feeling against African Americans for decades and it became a classic sundown town in which African Americans were unwelcome to reside. Pana is still a white town (more than 95%).