BACKGROUND

The French (from Canada) first entered the Illinois Indian tribal lands in the mid-17thcentury as traders and trappers. They were followed by Jesuit missionaries (such as Marquette) and explorers (such as Joliet), beginning in 1673. The Jesuits established missions, for instance at the Grand Village of the Kaskaskia (1673-1675) and the French began to build a series of forts, such as Crevecoeur in 1680 (near today’s Peoria), St. Louis in 1682 (at today’s Starved Rock), and Pimitéoui in 1691(also near today’s Peoria).

Who actually built these forts? Before 1719 when the Illinois Country became an official French-governed territory, the manual labor was that of men who accompanied the explorers, who were acting on behalf of the French king. Afterwards, it was soldiers who were building the forts, following orders.

FORT DE CHARTRES

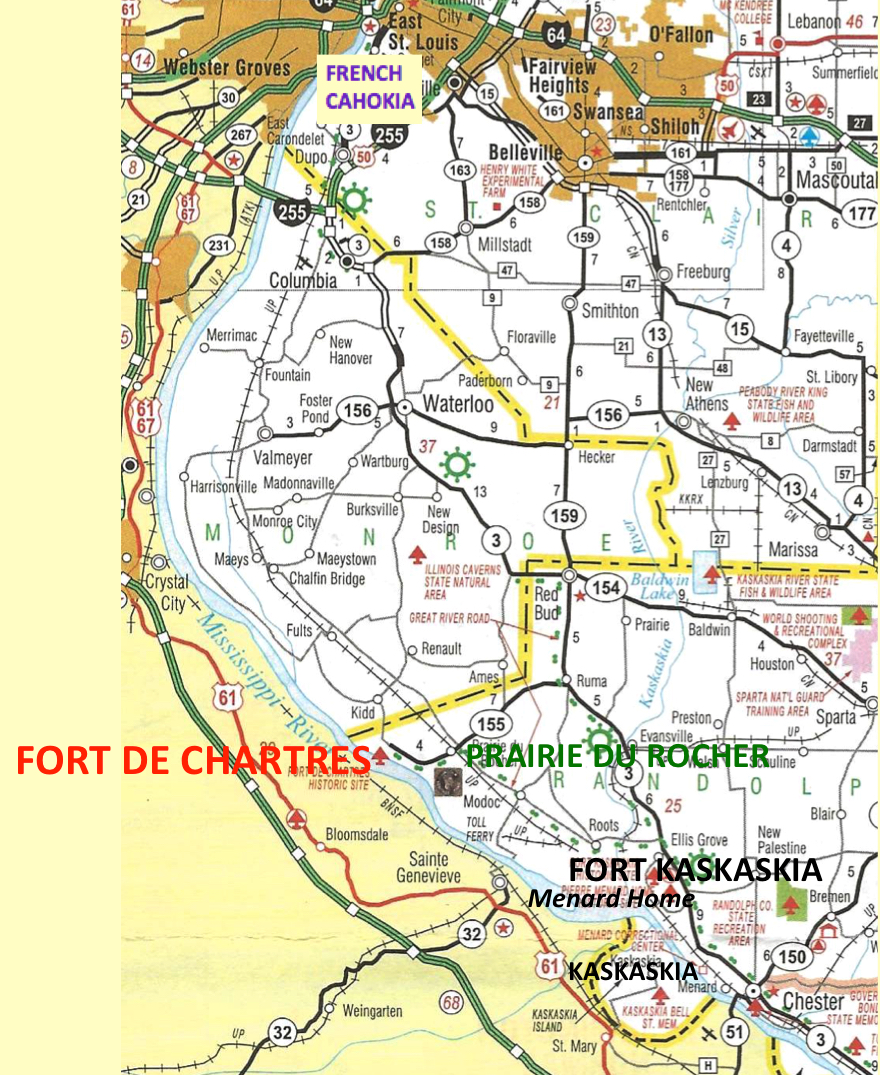

Fort de Chartres was created by order of the new provincial government that took over the Illinois Country which, until then (1719), had been a vast area of independently operating missions, traders, rare settlers, and Indians. The purpose in establishing the fort was protection against hostile Indians who were threatening trade, the delivery of provisions down river to the French colony in the lower Mississippi Valley, and the growing number of French arrivals seeking to make the Illinois territory their home.

There is no known plan of the first Fort de Chartres, which was built of wood in 1720. Historical documents indicate that there also was a second and third wood fort, but we lack drawings for them, too. Historical documents indicate that the earlier wood forts didn’t last long because of collapsing walls and inability to survive floods. By 1749 the third fort was in such disrepair that its military personnel were transferred to Kaskaskia.

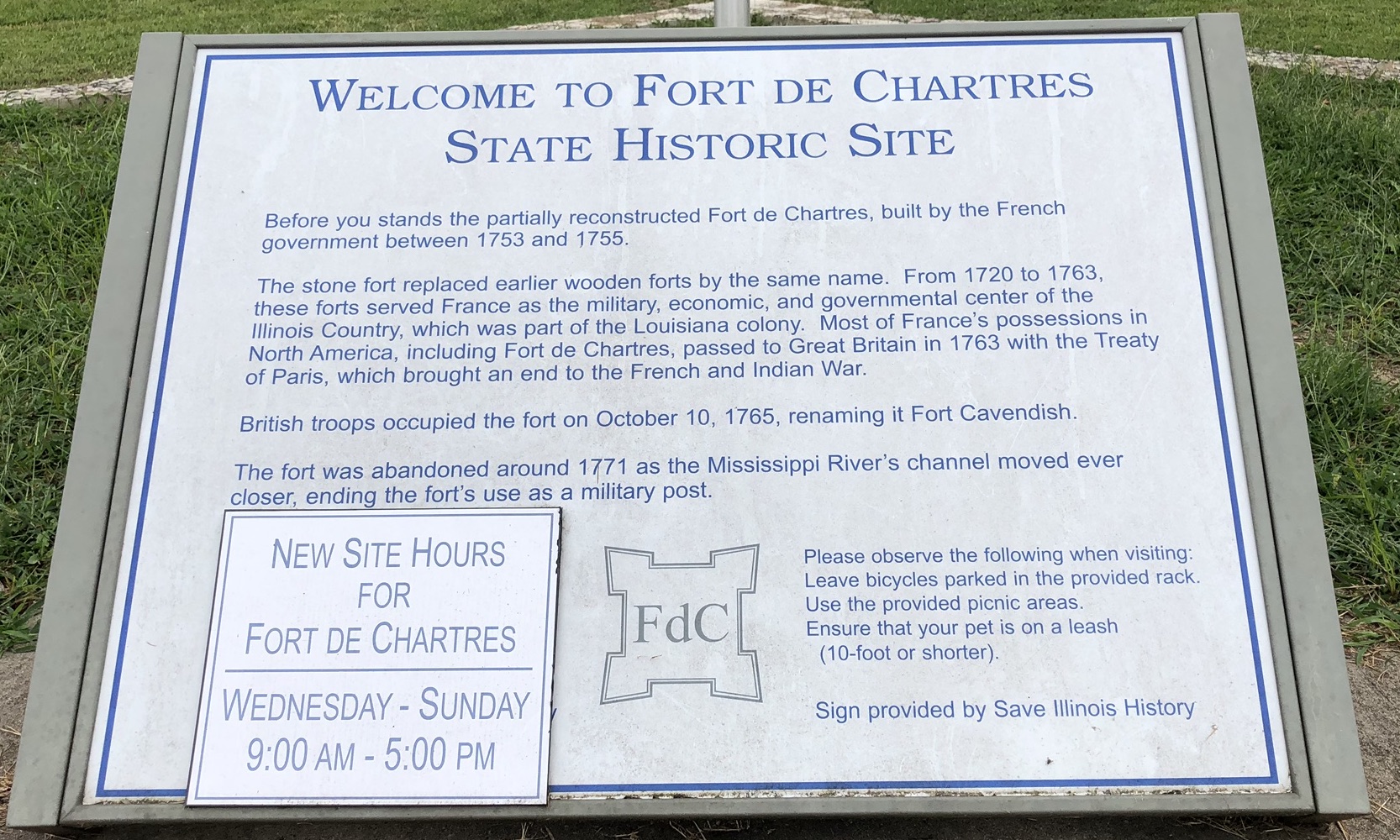

The massive stone fort we see today was built in 1753 and was fully operational in 1754. Construction of this new, strong fort became imperative when Indian hostility increased and French settlers were being attacked and French soldiers responded.

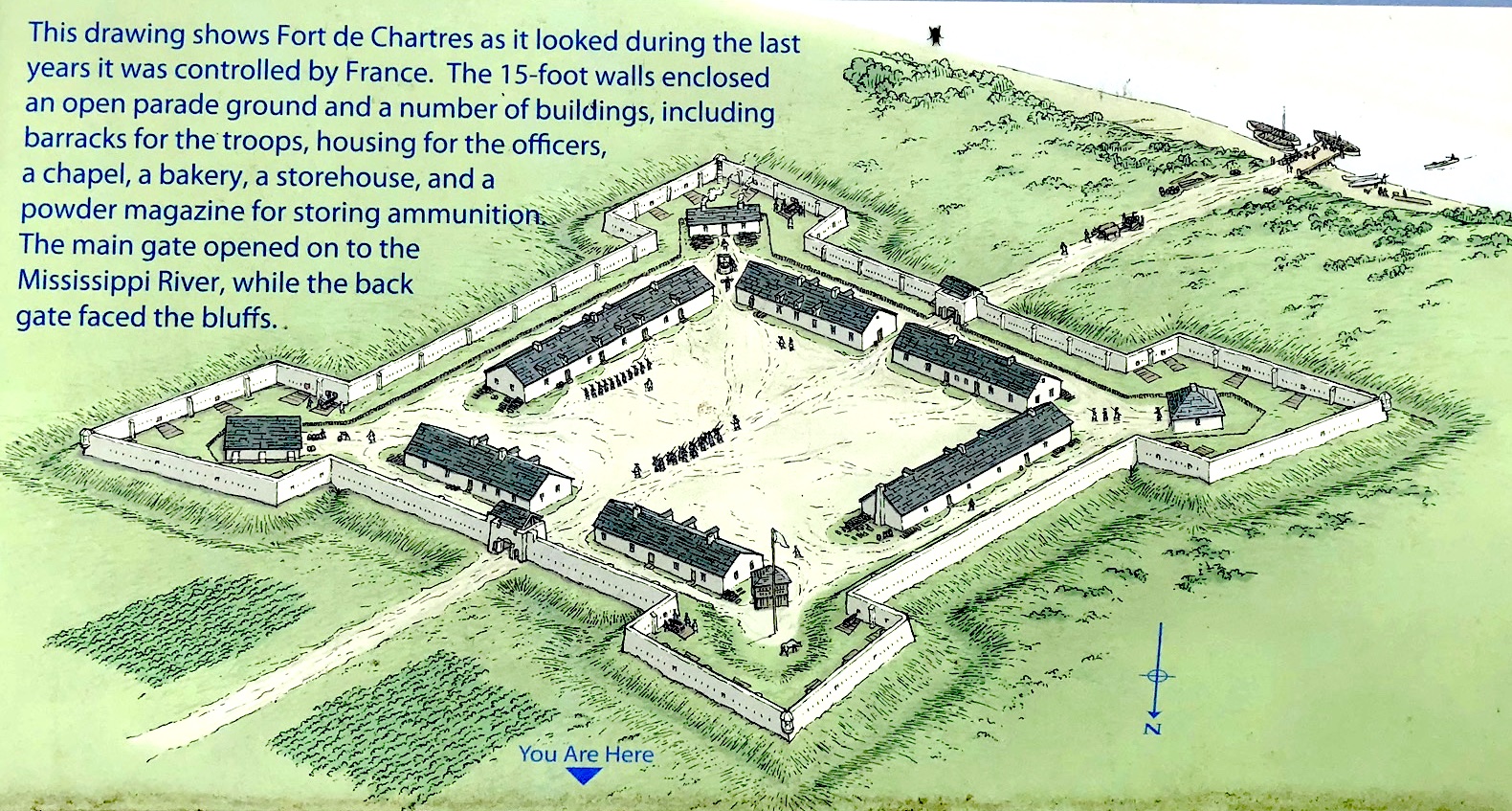

This Fort de Chartres became one of the strongest forts in North America and the key to the French defenses. In addition to its stone construction and four bastions, earthen embankments were constructed all the way around the fort.

This Fort de Chartres became one of the strongest forts in North America and the key to the French defenses. In addition to its stone construction and four bastions, earthen embankments were constructed all the way around the fort.

part of earthen embankment going around fort

part of earthen embankment going around fort

France’s North American territory (New France) passed to Great Britain at the end of the French and Indian War (1754-1763), during which the French, along with their Indian allies (such as the Illinois), fought the British with their Indian allies (such as the Iroquois). The war was ended in 1763 with the Treaty of Paris. Fort de Chartres was the last French post to be surrendered: it was occupied by a French garrison until 1765. British troops entered Fort de Chartres on October 10, 1765 and renamed it Fort Cavendish. Fort Cavendish was the seat of British government in the Illinois Country until 1772 when it was gravely damaged by the Mississippi River, which caused a collapse of the south wall of the fort. The fort was abandoned. Subsequently, the remaining walls and buildings fell into ruin.

On December 4, 1803, William Clark and several recruits passed by Fort de Chartres, which by then was a stone ruin. The party continued, picked up supplies, and then met Meriwether Lewis in Cahokia.

TODAY

The State of Illinois purchased the site of Fort de Chartres and made it a state park in 1916. In 1966 it was designated a National Historic Landmark. In 1974 it was inscribed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. The photo below was taken by Frank Melliere with an ultra-light airplane (courtesy of Brenda Owens):

One enters the fort through a massive wood door under the imposing stone gate. On the stone walls are two plaques (in French, in English) that explain the significance of the site.

The Guard House (LEFT below) was reconstructed in 1936. It contains a Catholic chapel furnished in the style of the 1750s, a priest’s room, a gunner’s room, an officer-of-the-day room, and a guard’s room. There is a combination museum and office building (RIGHT below), built in 1928 on the foundation of an original fort building. It houses exhibits depicting the history of Fort de Chartres and the Illinois Country.

The Powder Magazine (steep gabled building on left, below) is largely original. It is the oldest military structure in Illinois.

Above we have provided a basic summary of the tangible site and its role in North American history. It is a “cultural heritage site” — a tangible site. We also must consider the recent creation of an intangible cultural heritage at Fort de Chartres. Since 1970 an event called the “Rendezvous” has been held there, presented/hosted by Les Coureurs des Bois de Fort de Chartres [referring to the French traders and fur trappers of old] and sponsored by Les Amis du Fort de Chartres. As can be seen by the names, it is French heritage that is being recalled and celebrated, albeit with an admixture of fact and fiction: “The Fort de Chartres Annual Rendezvous features 1700s military units, traditional craft demonstrations, period music and dancing – all from the time when France controlled what is now Illinois. Visitors can watch muskets and cannons being fired, throw a tomahawk, buy hand-made crafts, learn about French kitchen gardens, taste delicious food and much more. This year’s event [2020 – it was cancelled because of the outbreak of Covid-19] also recognizes the 300th anniversary of the first of the four Fort de Chartres structures built and located in the strategic Mississippi River bottomland of Le Pays des Illinois.” Here is a youtube from a previous Rendezvous: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PXpG0biNVME

REFERENCES

Brown, Margaret Kimball. History as They Lived It. A Social History of Prairie du Rocher, Illinois. Southern Illinois University Press, 2005.

Encyclopedia of French Cultural Heritage in North America. On-line resource. http://www.ameriquefrancaise.org/en/article-675/Fort_de_Chartres_in_Illinois.html

Gale, Neil. “Fort de Chartres/Fort Cavendish and the Village of Nouvelle Chartres.” Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal. On-line resource. https://drloihjournal.blogspot.com/2017/10/fort-de-chartres-prairie-du-rocher.html

History Channel. “The French and Indian War Explained” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9n-gsgqaUo0

Mazrim, Robert F. At Home in the Illinois Country. French Colonial Domestic Site Archaeology in the Midwest 1730-1800. Studies in Archaeology No. 9, Illinois State Archaeological Survey, 2011.