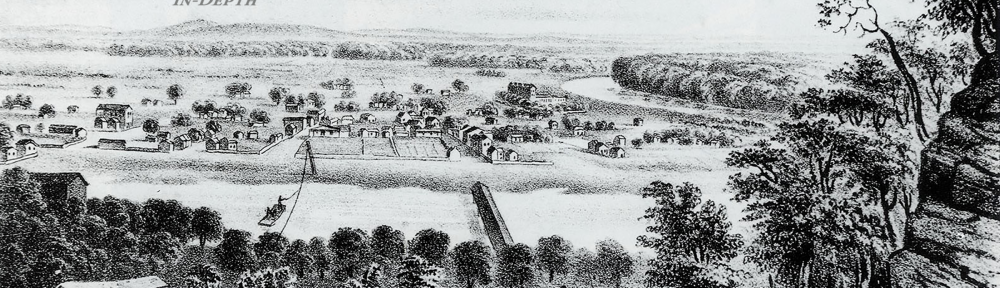

The image in the banner above is “View of Kaskaskia, 1841“, a lithograph by J.C. Wild and L. F. Thomas in their The Valley of the Mississippi Illustrated in a Series of Views (Chambers and Knapp, St Louis). It’s an important image because we see a raft being pulled with the aid of a wire to cross into Illinois from Missouri. We know this because still in 1841 Kaskaskia was a mainland settlement in Illinois. So the view must be from the Missouri side of the river looking east at Kaskaskia.

_________________________________________________________________________

In 1680 Iroquois Indians from the east invaded the lands of the Illinois Indians and destroyed the Great Village of the Kaskaskia (near today’s Starved Rock) that Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet had seen in 1673 and where Marquette had established a Mission of the Immaculate Conception in 1675. The Kaskaskia moved west to the area of today’s Peoria in 1691. But the Iroquois were still a threat, compounded by the Fox in the north and Sioux to the west. So they didn’t stay long. Still worried, they set up at Des Peres (on the south side of today’s St. Louis) but less than three years later moved again.

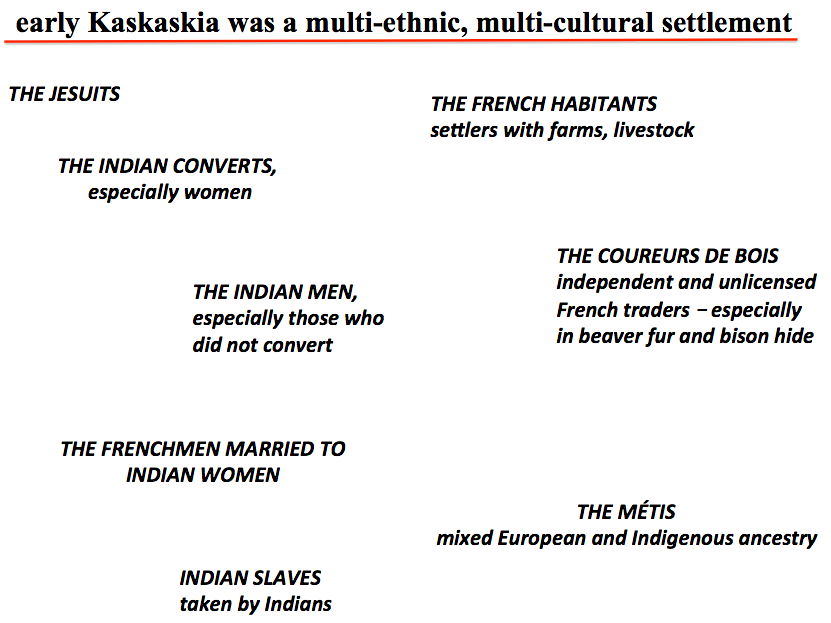

Thus, in 1703 perhaps one thousand members of the Kaskaskia tribe arrived at the peninsula of land between the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers. They were accompanied by Jesuit priests who had converted them and by French Canadian fur traders who had married Kaskaskia women. In European terms, this area was a kind of no-mans land. It was not administratively part of the French colony of Louisiana nor of New France (French Canada). It was the “pays de Illinois” – Illinois Country.

Thus, in 1703 perhaps one thousand members of the Kaskaskia tribe arrived at the peninsula of land between the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers. They were accompanied by Jesuit priests who had converted them and by French Canadian fur traders who had married Kaskaskia women. In European terms, this area was a kind of no-mans land. It was not administratively part of the French colony of Louisiana nor of New France (French Canada). It was the “pays de Illinois” – Illinois Country.

The Jesuits established a new Mission of the Immaculate Conception at Kaskaskia (named thus after the native tribe). And in the first twenty years the French/French Canadians and the Kaskaskia Indians lived close to each other and in constant interaction. In those years Kaskaskia developed into the most important French town in the middle/central Mississippi Valley based on the fur trade and related business and aided by the excellent location of the settlement.

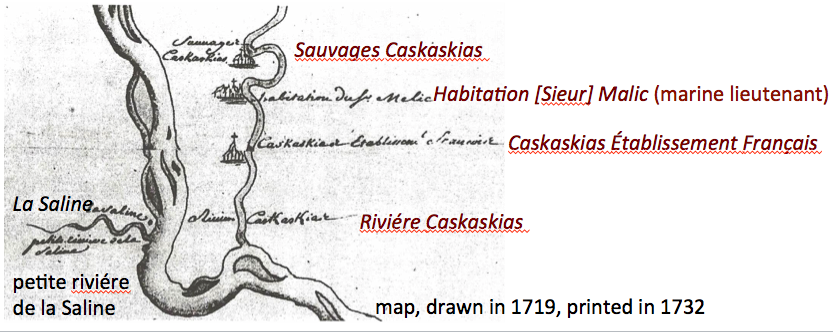

In 1717 France annexed the Illinois Country to Louisiana. And in 1719 France put order in the Illinois Country, and notably at Kaskaskia, by means of Boisbriant, the Lieutenant/Commandant. He enacted big changes on the ground at Kaskaskia. Importantly, in 1719 Boisbriant separated the French and Indians into two villages, each with a Catholic Church (a Jesuit mission for the Indians, a parish for the French).

As a major commercial hub, Kaskaskia was a bawdy town. Indeed, one reason given by the French administration for removing the Kaskaskia Indians from town to land 3 miles north, was to protect the Indian women from being debauched by rough boat men, traders and trappers and to stop the Indian men from excessive drinking. Another reason given was that the Indians were killing the settlers’ pigs. Yet another reason was the new French administration’s race policy, which sought to stop mixed-race marriage. But that was not successful in Kaskaskia.

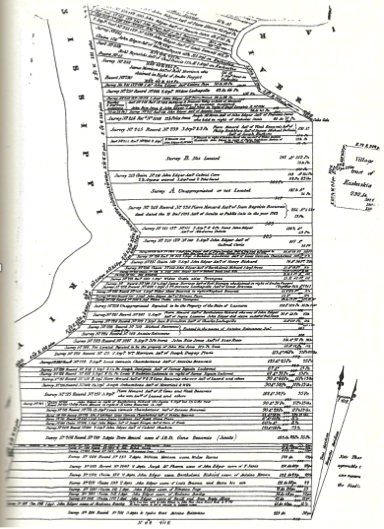

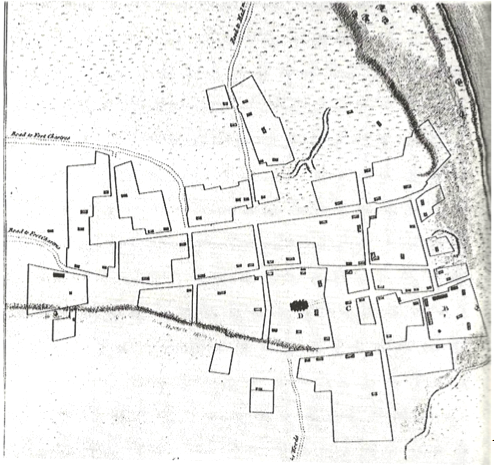

In addition to the missionary compound with church and arable land, the Jesuits owned other buildings in town. They were important in Kaskaskia but they did not control the town. Habitants (French agricultural settlers) started arriving and created houses on an enclosed lot of land having a garden and a stable for horses. Maps of the time indicate that the habitants laid out their land in an ancestral French pattern of long plowing strips or “longlots.” They also had access to common pasturage land for their livestock on which there also was wood for fuel. Kaskaskia developed – as did the other French settlements – a pattern of compact village, agricultural land in the form of strips, and common pasture lands.

source: French Roots in the Illinois Country by Carl J. Ekberg (2000) L: longlots;

R: compact Kaskaskia village

In 1722 this French town had almost as many residents as New Orleans. Kaskaskia became a cosmopolitan settlement in the Illinois Country. Its population encompassed Frenchmen from France, French Creoles, métis (what in Latin America are called mestizos) and African slaves. The Kaskaskia Indians moved freely in town, coming in from their now separated village – one observer estimated 200 Indian men. A 1732 census gave the population of Kaskaskia as 352, of whom half were French, of French descent, and Indian women who had married in. The other half were Black and Indian slaves.

Kaskaskia and the Illinois Country were unique in colonial North America because this cultural and racial mixture generated a particular behavior and way of life. However, amidst agricultural and trading prosperity there was insecurity and danger. The French were few in number in what still was Indian country. The Fox kept attacking and were eliminated only in 1730 by a combined French and Illinois tribal force. In the mid-1730s the Chickasaw – allied with the British – closed the Mississippi River almost for two years.

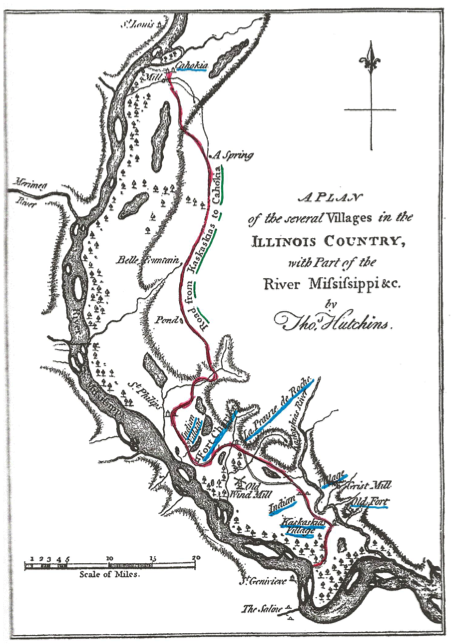

Kaskaskia’s farmers shipped tons of wheat downriver to feed southern Louisiana as well as vegetables and pork. Salt was an important industrial product whose source appears on the 1719/1732 map as La Saline, just across the Mississippi from Kaskaskia (see above).

Also contributing to the prosperity and excitement of the town, there were voyageurs doing business up and down the big river and stopping at Kaskaskia. And a lot of movement by land. Traders bartered native goods for European goods. Fur of almost any animal remained valuable.

In 1741 King Louis XV gave a large cast bell to the Mission of the Immaculate Conception Church in Kaskaskia. The bell is inscribed: Pour l’église des Illinois par les soins du roid’outrel’eau. (For the Church of the Illinois, by gift of the King across the water). On one side of the bell are the Royal lilies of France. A cross and a pedestal with the fleur de lis appear on the other side. The 650-pound bell was shipped from France to New Orleans and then pulled up the Mississippi River by ropes on a bateau, arriving in 1743. Today the bell is housed in a red brick building called Kaskaskia Bell State Memorial, which was built by the State of Illinois in 1948.

source: https://www.greatriverroad.com/fcc-attraction-pages/kaskaskia-bell

source: https://www.greatriverroad.com/fcc-attraction-pages/kaskaskia-bell

The strategic location of Kaskaskia and the success of the town in the intertwined French Colonial and Native American landscape is manifested over sixty miles of this territory by the Kaskaskia-Cahokia Trail with Kaskaskia as the origin of the trail and Cahokia. The two French villages (Kaskaskia and Cahokia) were named after local Indian tribes and Indians had walked this route long before the French made use of it. This is Thomas Hutchinson’s 1771 map on which he marks the Kaskaskia-Cahokia Trail (red) and indicates the villages (blue) of Kaskaskia, Indians, Prairie de Rocher, and Cahokia as well as Fort de Chartres.

The short-lived and unfinished Fort Kaskaskia was supposed to protect the nearby town of Kaskaskia from hostile Indians and enemy Europeans. It did not do a good job. The French were ousted by the British from their North American holdings in 1763. British forces entered what had been the Illinois Country.

The short-lived and unfinished Fort Kaskaskia was supposed to protect the nearby town of Kaskaskia from hostile Indians and enemy Europeans. It did not do a good job. The French were ousted by the British from their North American holdings in 1763. British forces entered what had been the Illinois Country.

Moreover, the dismal fate of Kaskaskia was already being written by the Mississippi River. In 1765 a visiting British captain observed that the river was dangerous with banks collapsing and logs and debris being carried by the downstream current with tremendous force.

In 1778 the Americans laid claim to Kaskaskia, led by George Rogers Clark (older brother of William Clark who subsequently would be eponymous in the Lewis and Clark expedition). George Rogers Clark was commissioned by Patrick Henry to fight the British and their Indian allies for the strategic area at the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, including the towns of Kaskaskia and Cahokia. George Rogers Clark and his men left Kaskaskia in 1780, leaving Kaskaskia without a government in a region that was lawless. It’s been written that gangs of thugs made corrupt alliances with merchants and land speculators and intimidated the still French population of town. Over the next ten years the formerly prosperous town descended into chaos. Leading citizens left. Population declined.

In 1785 the Mississippi River flooded drastically, damaging every building in Kaskaskia – a portent of worse to come.

In 1809 the U.S. federal government created the Illinois Territory and soon began selling land there – regardless of what Indians may have been occupying parts of it. This represented a boon for Kaskaskia for as a large settled town it became a first port of call for many would-be settlers.

In 1818 Kaskaskia was named the capital of the new State of Illinois. It had a population of about 7,000. But a year later the capital was transferred to Vandalia and then to Springfield. Meanwhile, the fur trade, which had been responsible for so much of Kaskaskia’s prosperity, declined.

The definitive start of Kaskaskia’s ill fate happened in 1844 when the Mississippi River dramatically flooded and inundated the town. Many houses collapsed. Many residents left.

The definitive start of Kaskaskia’s ill fate happened in 1844 when the Mississippi River dramatically flooded and inundated the town. Many houses collapsed. Many residents left.

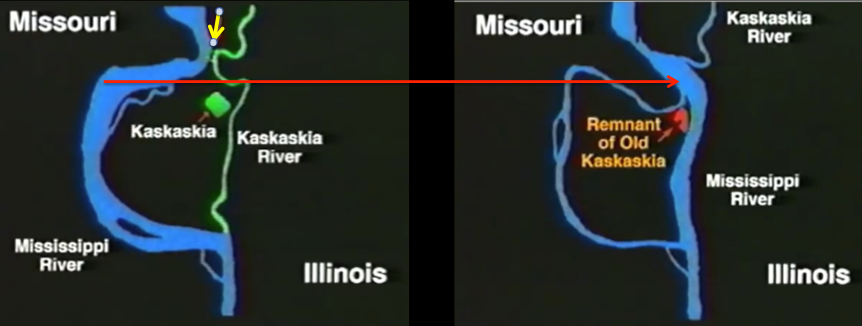

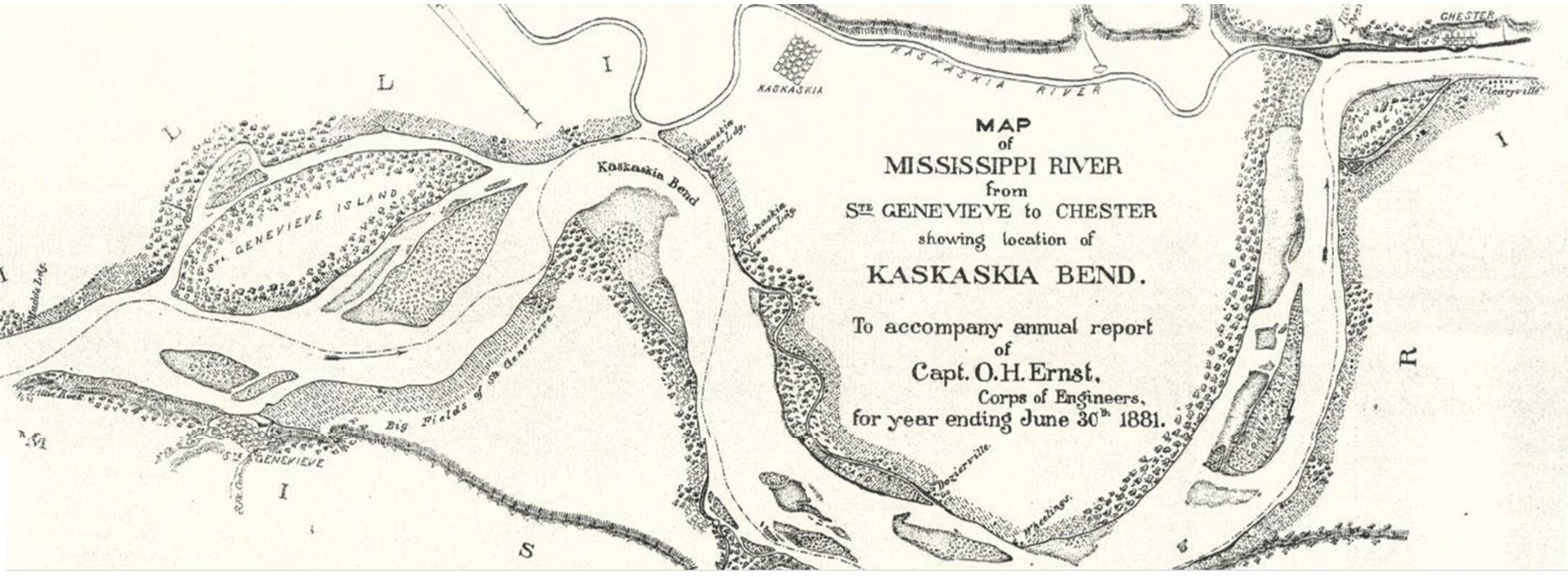

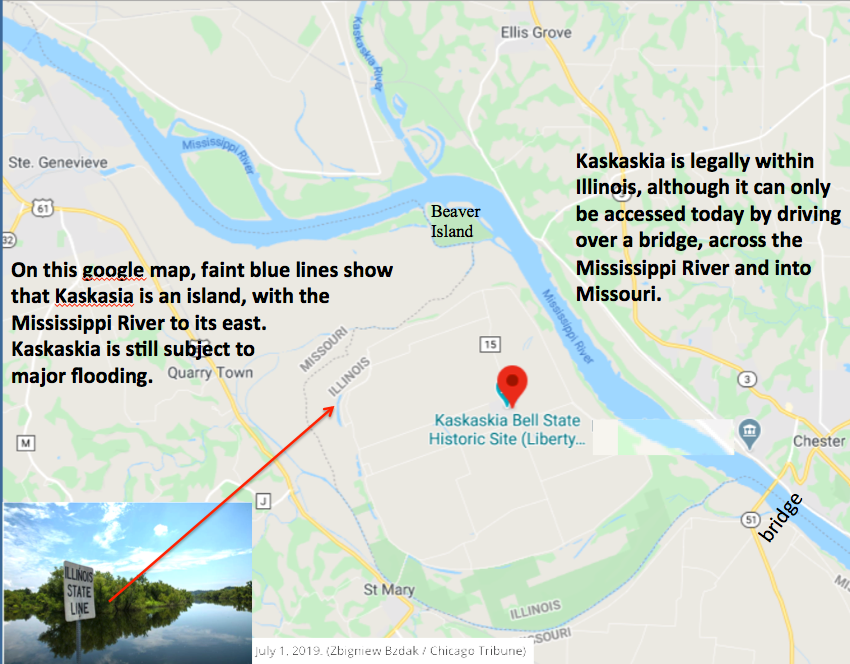

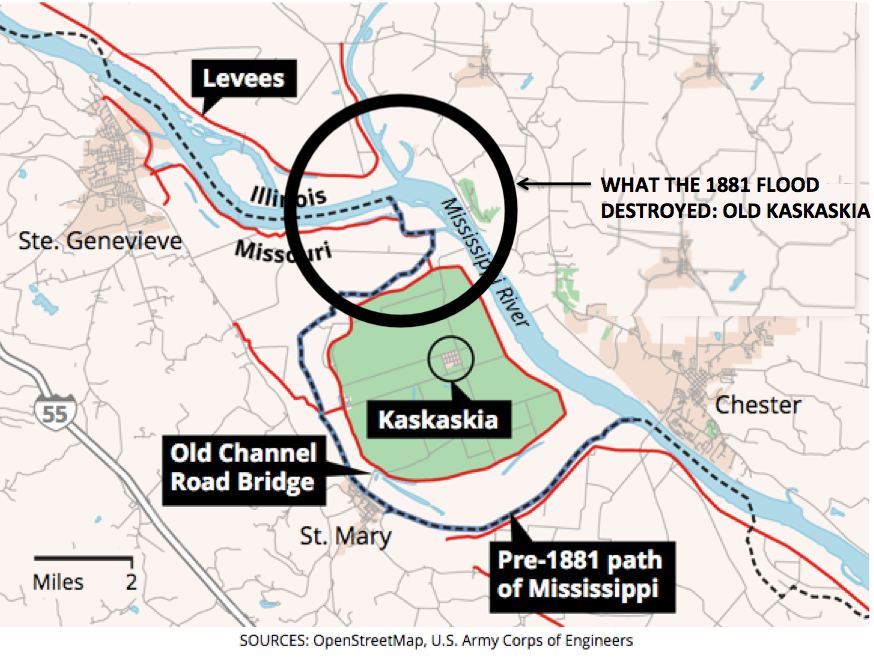

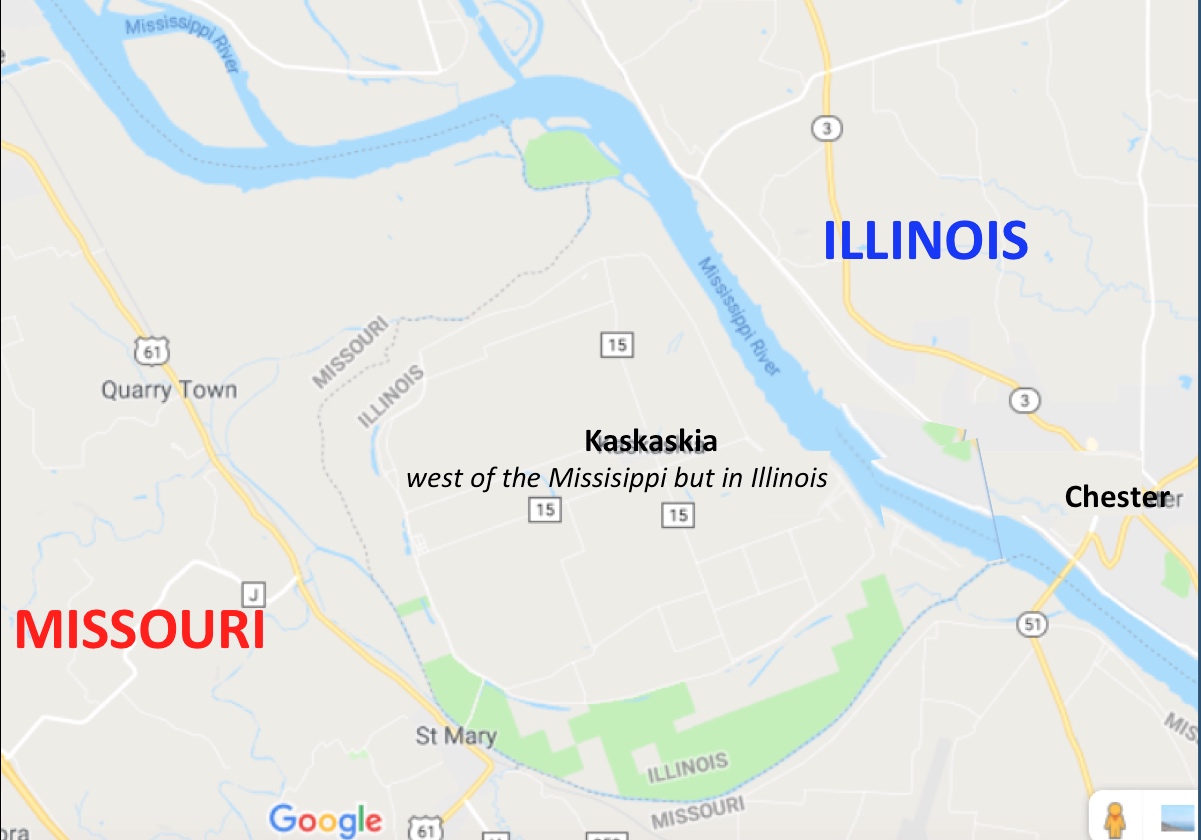

In 1881 disaster struck again. This time the Mississippi River shifted its course eastward by breaking through a narrow strip of land (yellow arrow). The Mississippi flooded into the Kaskaskia River to the east.

There was massive loss of land and over the following decade buildings crumbled into the river. Written accounts as well as historical photographs show the massive destruction.

There was massive loss of land and over the following decade buildings crumbled into the river. Written accounts as well as historical photographs show the massive destruction.

Kaskaskia became an island in the new channel cut by the Mississippi River.

Kaskaskia did not recover. A brave few moved to higher ground to create New Kaskaskia. But they were now living on an island and their descendants still do.

In 1892 graves from Kaskaskia’s cemetery were moved to Garrison Hill and reburied. Many are the graves of French families.

The Mississippi River has continued to flood with two devastating events in 1993 and 2019. The 2019 event (below) may resemble what the Kaskaskia residents saw in 1881.

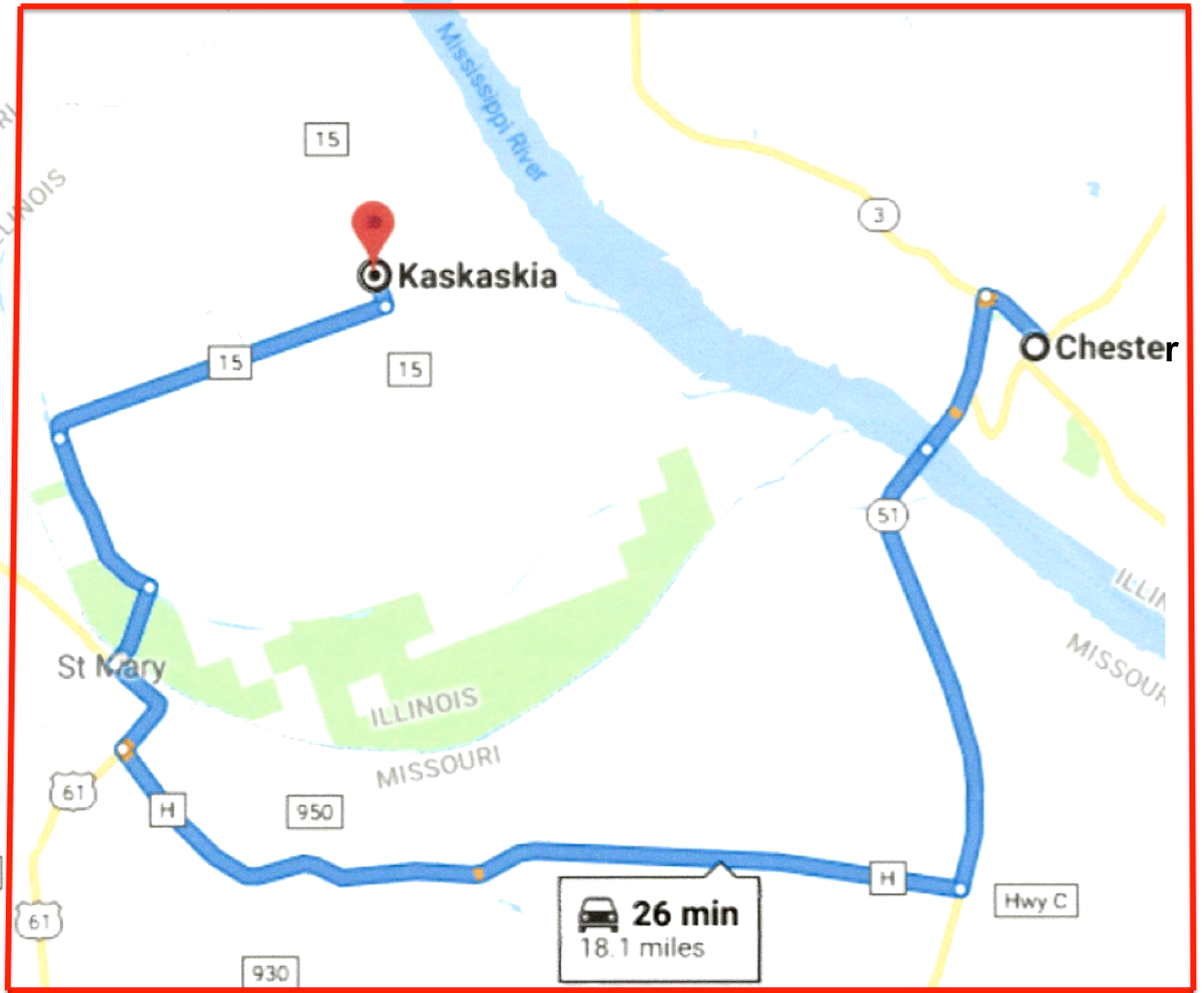

It is tremendously interesting to visit the island and to contemplate the history summarized on this web page. If one uses one’s imagination while looking at the Mississippi River, and if one looks at the images on this webpage, then on a summer day it is almost possible to imagine the early French and Indian settlers and the notable history that was made at this place.

Here is how to get there!

REFERENCES

Belting, Natalia Maree. Kaskaskia Under the French Regime. Originally 1984. Southern Illinois University Press, 2003. available on line: https://archive.org/stream/kaskaskiaunderfr00belt/kaskaskiaunderfr00belt_djvu.txt

Brown, Stuart. Old Kaskaskia days and way. Transactions of the Illinois State Historical Society ,1905 http://www.museum.state.il.us/RiverWeb/landings/Ambot/Archives/transactions/1905/Old_20Kaskaskia.html

Butler, W. M. 1912. Historical sites and scenes in Randolph County, Illinois. Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 4 (4): 459-468.

Dewar, David P. 2009. Migration to acculturation. Ohio Valley History 9 (3): 3-24. Ekberg, Carl J. French Roots in the Illinois Country. The Mississippi Frontier in Colonial Times. (University of Illinois Press, 2000)

Hauser, Raymond E. 1976. The Illinois tribe: from autonomy and self-sufficiency to dependency and depopulation. Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 69(2): 127-138.

Keene, David J. War and the colonial frontier. IN: The Archaeology of French and Indian War Frontier Forts, edited by Lawrence E. Babits and Stephanie Gandulla, pp. 229-239. University Press of Florida, 2013.

Leavelle, Tracy Neal. The Catholic Calumet: Colonial Conversions in French and Indian North America. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011.

MacDonald, David and Raine Waters. Kaskaskia. Lost Capital of Illinois (Shawnee Books, 2019). (and listen to the audio summary: https://will.illinois.edu/news/story/illinois-issues-kaskaskia–the-lost-capital-of-illinois

Mazrim, Robert F. At Home in the Illinois Country. Illinois State Archaeological Survey, Studies in Archaeology, 9. University of Illnois Press, 2011.

Momo Momo. Kaskaskia shot with a drone: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y0QaixYTZcM

Morrissey, Robert Michael. Empire by Collaboration. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015. (see summary: https://blogs.illinois.edu/view/6367/237921)

Morrissey, Robert Michael. The terms of encounter. French and Indians in the Heart and North America, 1630-1815, edited by Robert Englebert and Guillaume Teasdale, pp. 43-75. Michigan State University Press and University of Manitoba Press, 2013.

Reda, John. From subjects to citizens. French and Indians in the Heart and North

America, 1630-1815, edited by Robert Englebert and Guillaume Teasdale, pp. 159-181. Michigan State University Press and University of Manitoba Press, 2013.

Stelle, Lenville J. Inoca Ethnohistory Project. Parkland Coilege, Champaign, 2005.

Temple, Wayne. Indian Villages of the Illinois Country. Historic Tribes. Illinois State Museum, Scientific Papers, Volume II, Part 2, 1958.

Walthall, John A. (ed.) French Colonial Archaeology: The Illinois Country and the Western Great Lakes. University of Illinois Press, 1991.

For a comparison today about the meandering and flooding of the Mississippi River and how it contrasts with state boundaries previously drawn along the river, see: https://scitechdaily.com/meandering-mississippi-river-photo-taken-by-astronaut-on-space-station-shows-divergence-from-state-boundaries/