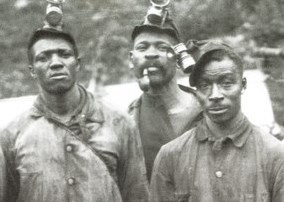

There were Black coal miners in Illinois and other states. They suffered not just the usual hardships of their job but also less pay, even worse working conditions and the racism of the European immigrant coal miners and their descendants. They were pawns of the bosses in various strikes where they were brought in to scab and therefore faced the fury of union/unionizing white miners. Four cases stand out in the Illinois mine wars. A fifth, however, shows peaceful racial co-existence.

U.S. National Park Service photo

U.S. National Park Service photo

1877 Braidwood Strike This strike adumbrated others that would happen two decades later in southern Illinois. At Braidwood (60 miles SW of Chicago) the mine company brought in African Americans from the south with the assumption that not only could the Black miners break the strike, they also would not be inclined to join the nascent union because the union’s racism would prevent recruitment. The Braidwood bosses deployed their militias against the strikers and the Black strikebreakers fled in fear of the white miners; some were moved to other parts of the country to break new strikes. A small number stayed and after the strike worked in the mine alongside white miners, without further incident. In 1883 the Diamond Coal Mine suffered a major disaster, killing 74 miners. There is a memorial monument in town. We do not know if any of the victims were Black.

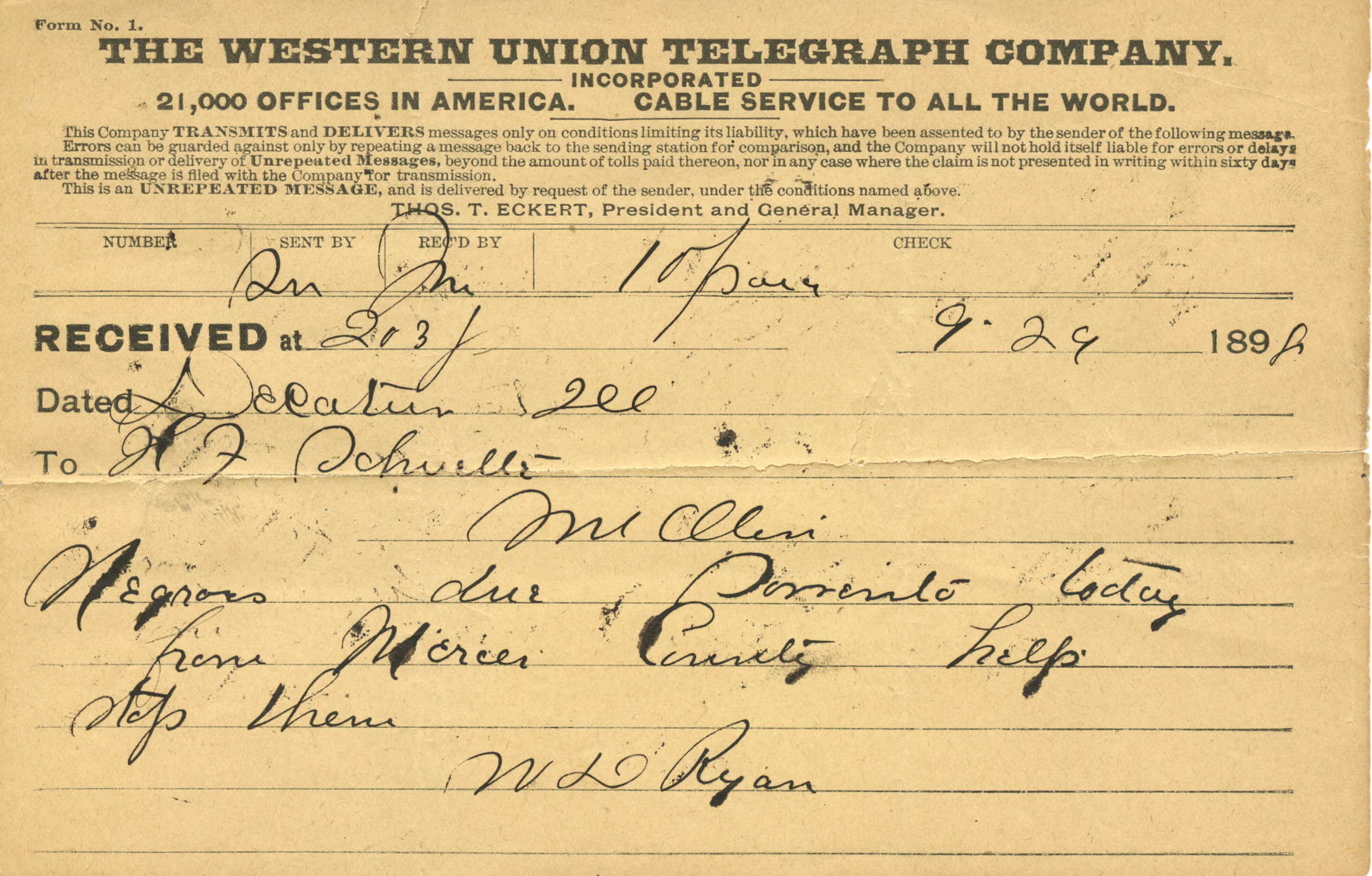

Battle of Virden The labor strife at Virden in 1898 was ignited when the mine company refused to pay the going rate and instead imported African American miners from Alabama as strikebreakers or scabs. In the ensuing violence between miners and the mining company, the African Americans were able to avoid injury and returned home or moved elsewhere. The image below is from the John Keiser Collection that was gifted by his family to the Mother Jones Museum in Mt Olive. It is one of several priceless telegrams bemoaning the arrival of African American miners.

“Negroes due … today … help stop them.”

“Negroes due … today … help stop them.”

Original telegram in the collection of the Mother Jones Museum in Mt Olive.

This and other Virden telegrams were gifted to the Mother Jones Museum in Mt Olive by the Estate of historian John Keiser. The image above is used with the Museum’s permission. This image may not be copied, reproduced on another website or reproduced in a publication without the explicit permission of the Board of the Mother Jones Museum in Mt Olive.

Pana Riot In 1899 the mining company at Pana (40 miles SE of Springfield) tried the same script as in Virden by importing African American miners, again from Alabama, with the Governor siding against the white miners who tried to convince the Blacks to desist. Indeed, several organized groups made contact with the African American miners in Alabama to inform them of the exploitative labor situation in Pana. Researcher Noah Lenstra writes, “the Alabama Miners’ Union and the Afro-American Labor and Protective Association worked with the United Mine Workers of America to prevent more blacks from moving north” (p. 21). Racist hostility in Pana (and Illinois) also deterred some Blacks from arriving. But many persisted claiming a right to work and live in Pana. The strike was accompanied by violence on both sides: the miners and the mine owners with their collaborators. After several weeks and five Black deaths the National Guard was called in. “Afro-phobia” (as it was called by one source at the time cited by Dr. Lenstra) spread widely out of Pana into the state. Pana’s Black population moved back to Alabama or set out west.

Carterville Riot In 1899 The Big Muddy Coal Company was trying to run its mine with non-union miners while the miners were trying to gain recognition of their union. The mining company repeated the Braidwood strategy: bringing in African American miners to scab. The train carrying them was assaulted by Union miners and armed violence broke out. Governor Tanner sent in troops to restore order. The racial strife intensified when the union miners objected to the Black presence not just in the company mine but also in town itself after the troops were withdrawn. The white miners fired upon the African Americans coming into town, in what Governor Tanner condemned as premeditated murder. Seven died. Troops were again sent in so that the mine could continue to work but the union miners declared that they would drive out the Black men. This Carterville riot followed Pana by only a few months.

Du Quoin Du Quoin (20 miles north of Carbondale) was an early center of mining. Before and after the Civil War it had a minority population of African Americans. They continued to live in Du Quoin. In other words, the African Americans were not imported strikebreakers. They were part of the community, notwithstanding various aspects of segregation. The Black community of Du Quoin was at the very forefront of the process of unionization in the dynamic period between the late 1800s-early 1900s. As Dr. Lenstra reveals, the black community here enjoyed “a measure of respect often withheld from black miners elsewhere in the state, where indeed the word black was often synonymous with scab at this time.” Black miners worked underground alongside White miners and they were union men. This proximity seems to have resulted in a non-volatile situation above ground where the racial hierarchy, nevertheless, played out.

Aftermath In the early 1920s the United Mine Workers of America became an integrated union.

KEY REFERENCE

Lenstra, Noah. The African American Mining Experience in Illilnois from 1800-1920. https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/bitstream/handle/2142/9578/BlackMinersIllinois.pdf?sequence=2

COMING SOON! The Illinois State Historical Society has approved (in Fall 2022) a proposal for a historical marker in Springfield that will commemorate that city’s African American miners. This announcement will be updated as soon as the marker is created.

banner image of Black coal miner: wikimedia.commons