The Conduct of Life by Ralph Waldo Emerson (1860) III: Wealth. “The price of coal shows the narrowness of the coal-field, and a compulsory confinement of the miners to a certain district. All salaries are reckoned on contingent, as well as on actual services. …

In 1916 Carl Sandburg, American poet and Illinois native son wrote these words: Do you know that all the great work of the world is done through me? I am the workingman… — We think Sandburg’s words are a fitting introduction to this part of the project that studies coal mining communities in downstate Illinois, many of which have seen great labor struggles and various of which have memorials to the men who lost their lives by working in the mines or to labor violence. The plight of exploited miners and the labor battles that resulted are well presented in PBS’ “American Experience” Season 28, Episode 2: https://www.pbs.org/video/american-experience-coal-towns-mine-wars/

Sixteen Tons, composed in 1946 by Merle Travis, a miner, and most famously rendered by Tennessee Ernie Ford in 1956. Listen to its description of the exploitation of the miners by the mine owners:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jIfu2A0ezq0

“You load sixteen tons, what do you get?

Another day older and deeper in debt

… I owe my soul to the company store

… I picked up my shovel and I walked to the mine

I loaded sixteen tons of number nine coal”

And listen to Jimmy Dean’s similarly popular 1961 song, Big Bad John, which imagines a mining disaster:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KnnHprUGKF0

… “Then came the day at the bottom of the mine when a timber cracked and men started cryin.’ Miners were prayin’ and hearts beat fast and everybody thought that they had breathed their last … Then a miner yelled out ‘there’s a light up above’ and twenty men scrambled from a would-be grave. … Then came that rumble way down in the ground. Then smoke and gas belched out of that mine. Everybody knew it was the end of the line for Big John…”

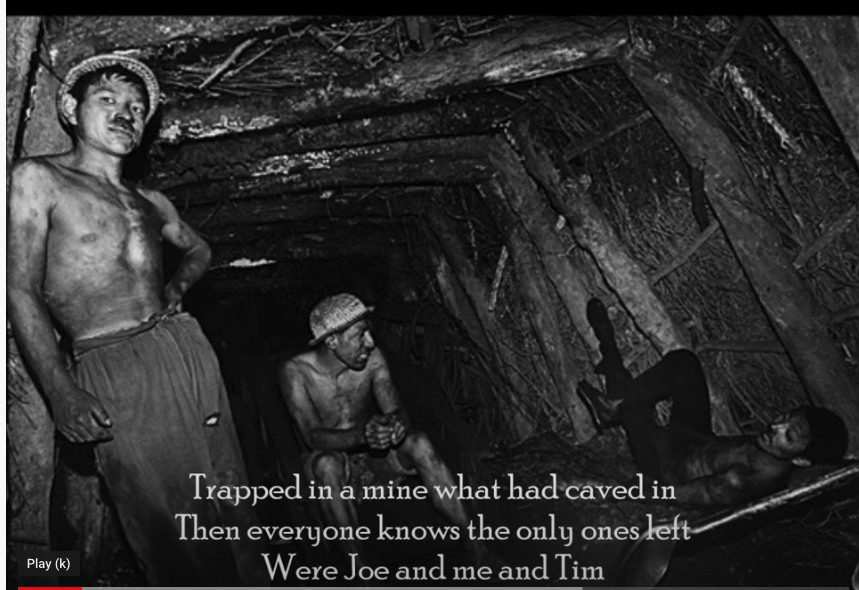

The image above is from the 1970 song, “Timothy“, by The Buoys, also about a mine collapse.

And yet miners did not abandon this profession, notwithstanding its physical danger, damage to their health, and abusive terms of employment. Roger Kratchovil of Mt. Olive, in an essay called “The Pride of Being a Coal Miner”, writes: “The coal miners loved working in the mines … [it] was part family tradition and part having a job. Danger lurked everywhere, lung diseases … could be your destiny … and there was always the dreaded threat of injuries … I have always found miners to be tough, brave, strong, and most importantly they always seem to stick together… they view dangers as just a part of the job and it serves as a bonding feature.” This pride is obvious in the pins sold at the Gillespie Coal Museum, which say: “If you ain’t a coal miner, you ain’t shit”.

EXCITING NEWS! (August 10, 2023): explore the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) digital archive collection, now accessible at https://umwa.org/umwa-collection-archive/

AND WATCH THIS UMWA DOCUMENTARY!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K5nzONL68Rs&t=220s

Coal mining played an especially significant role in the labor movement in the United States because of the miners’ heroic struggles against their heartless exploitation by rapacious mine owners. That history also includes the bloody battles waged by the United Mineworkers of America and the Progressive Miners of America against each other, which fractured their common purpose. And coal mining was rife with mine disasters, claiming lives. Throughout, the miners persevered.

Coal mining played an especially significant role in the labor movement in the United States because of the miners’ heroic struggles against their heartless exploitation by rapacious mine owners. That history also includes the bloody battles waged by the United Mineworkers of America and the Progressive Miners of America against each other, which fractured their common purpose. And coal mining was rife with mine disasters, claiming lives. Throughout, the miners persevered.

Travel through southern Illinois can be a trip through the visible landscape of American labor history. Each town we have chosen is an important reference point in that story. Whether you explore the “coal triangle route” immediately south of Springfield or extend your trip to the coal towns in far southern Illinois (see the memorials in Marissa, West Frankfort, Herrin), learning about labor heritage in towns where it is recalled will cause you to think deeply about social justice, economic equity and the racial and ethnic dimensions of labor.

THE FIRST NATIONAL LABOR UNION

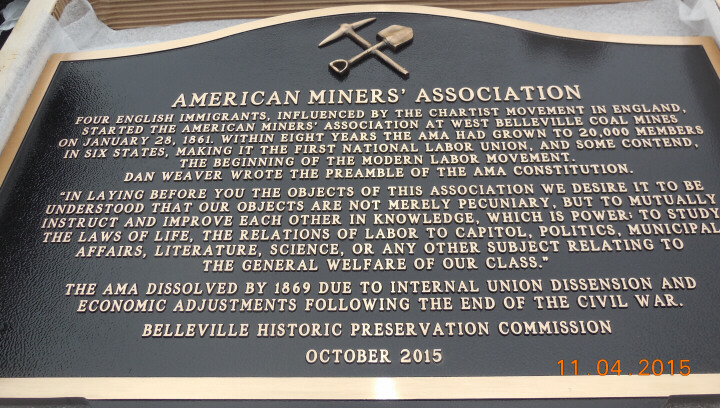

Remarkably, miners in Illinois started an early labor union before the Civil War. As explained on a bronze plaque erected by the Belleville Historic Preservation Commission in October 2015:

Four English immigrants, influenced by the Chartist movement in England, started the American Miners’ Association at West Belleville Coal Mines on January 28, 1861. Within eight years the AMA had grown to 20,000 members in six states, making it the first national labor union, and some contend, the beginning of the modern labor movement. / Dan Weaver wrote the Preamble of the AMA Constitution. / “In laying before you the objects of this association we desire it to be understood that our objects are not merely pecuniary, but to mutually instruct and improve each other in knowledge, which is power. To study the laws of life, the relations of labor to capitol [sic], politics, municipal affairs, literature, science, or any other subject relating to the general welfare of our class.” The AMA dissolved by 1869 due to internal union dissension and economic adjustments following the end of the Civil War.

Karl Marx’s Das Capital was published in 1867, six years after these English coal miners wrote their own manifesto. They also enunciated a relationship between knowledge and power more than a century before Michel Foucault published his Knowledge and Power (1980).

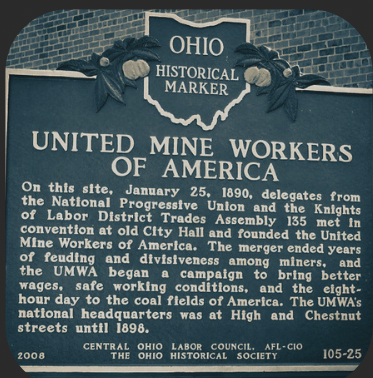

BIRTH OF THE UMW The United Mine Workers (later United Mine Workers of America) was founded in Columbus, Ohio in 1890. Its goal was to address and redress the horrific working conditions of miners including miserable pay, extreme lack of safety in the hazardous mines, the company town economic system that kept them indebted and trapped, and irregularity of work. Sources differ on the important point of whether the UMW was founded as a racially integrated union or subsequently became so.

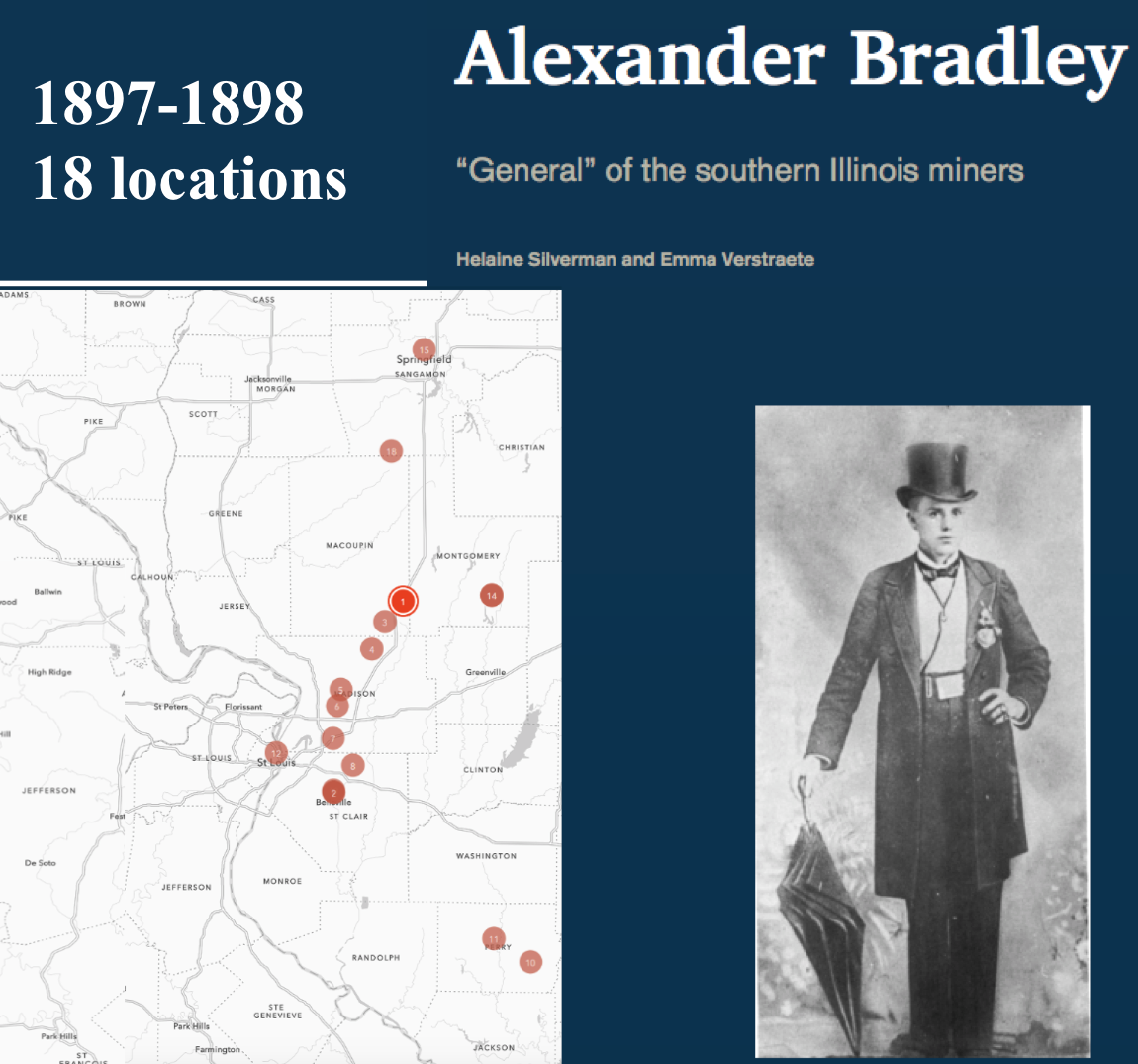

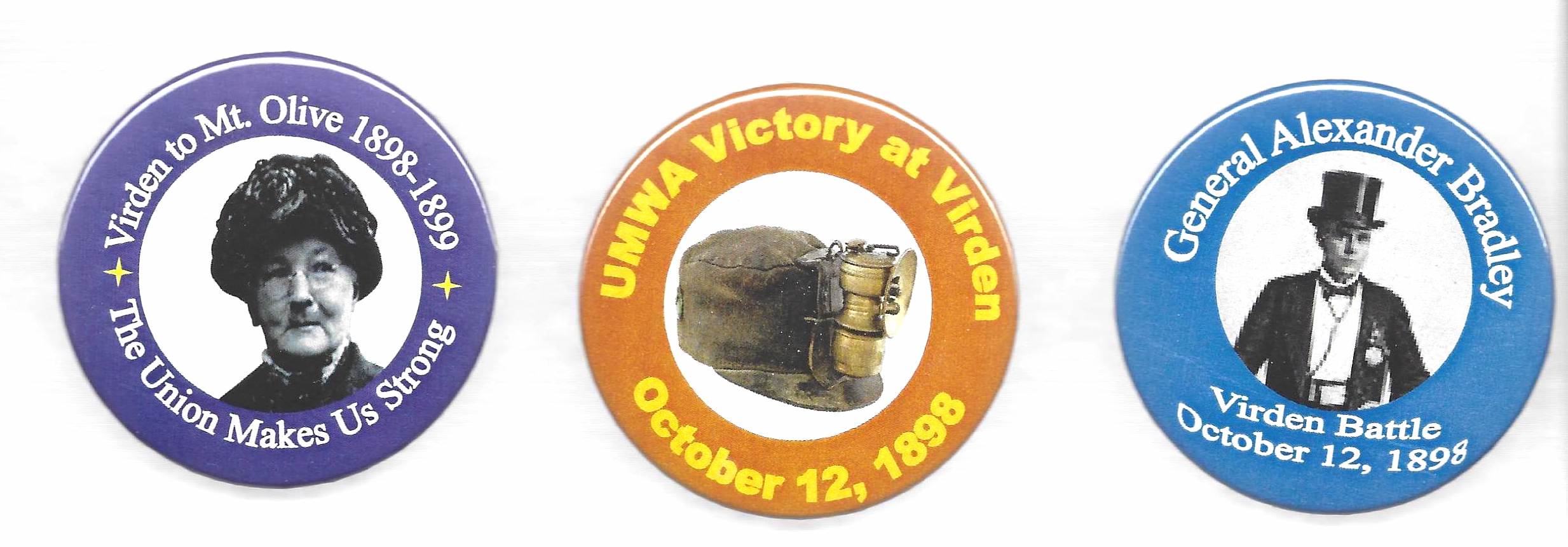

THE EARLY UMW IN ILLINOIS The UMW called for a general strike across the nation in 1897. There were fewer than four hundred members in Illinois at that time. Everything changed when Alexander Bradley began to unionize the mines in southern Illinois. Declaring himself “General” Bradley and sporting a Prince Albert top coat and a silk top hat Bradley became the immediately recognizable figure of labor in southern Illinois. He was an exceptional orator and charismatic person to judge by the tremendous growth in union membership under him. Click on the hyperlink to explore our General Bradley story map: https://arcg.is/0KajSW

Bradley’s role in the UMW was significant for he brought the numerous and militant southern Illinois miners into the union, supporting the UMW’s platform which achieved an 8-hour shift, a 6-day week, major concessions on working conditions, and a 30% wage increase. Moreover, Bradley and the UMW were able to create a space in which the numerous European immigrant miners = many of whom did not speak English or barely so – were welcomed alongside the “native” miners. Seeing this united front and notwithstanding the deal with the UMW, in some Illinois coal towns the mine owners sought to break the strikes with cheaper labor and the sowing of a new line of division amongst the ethnically diverse miners by recruiting southern African American miners.

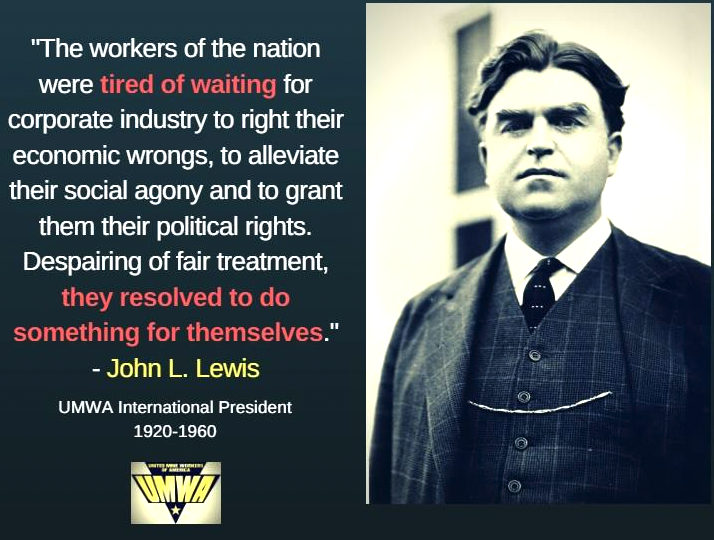

Only eight years after its founding the UMW won a contract for an 8-hour working day. The schedule was implemented on April 1, 1898, a year after the great strike of 1897.

Only eight years after its founding the UMW won a contract for an 8-hour working day. The schedule was implemented on April 1, 1898, a year after the great strike of 1897.

THE PROGRESSIVE SPLIT

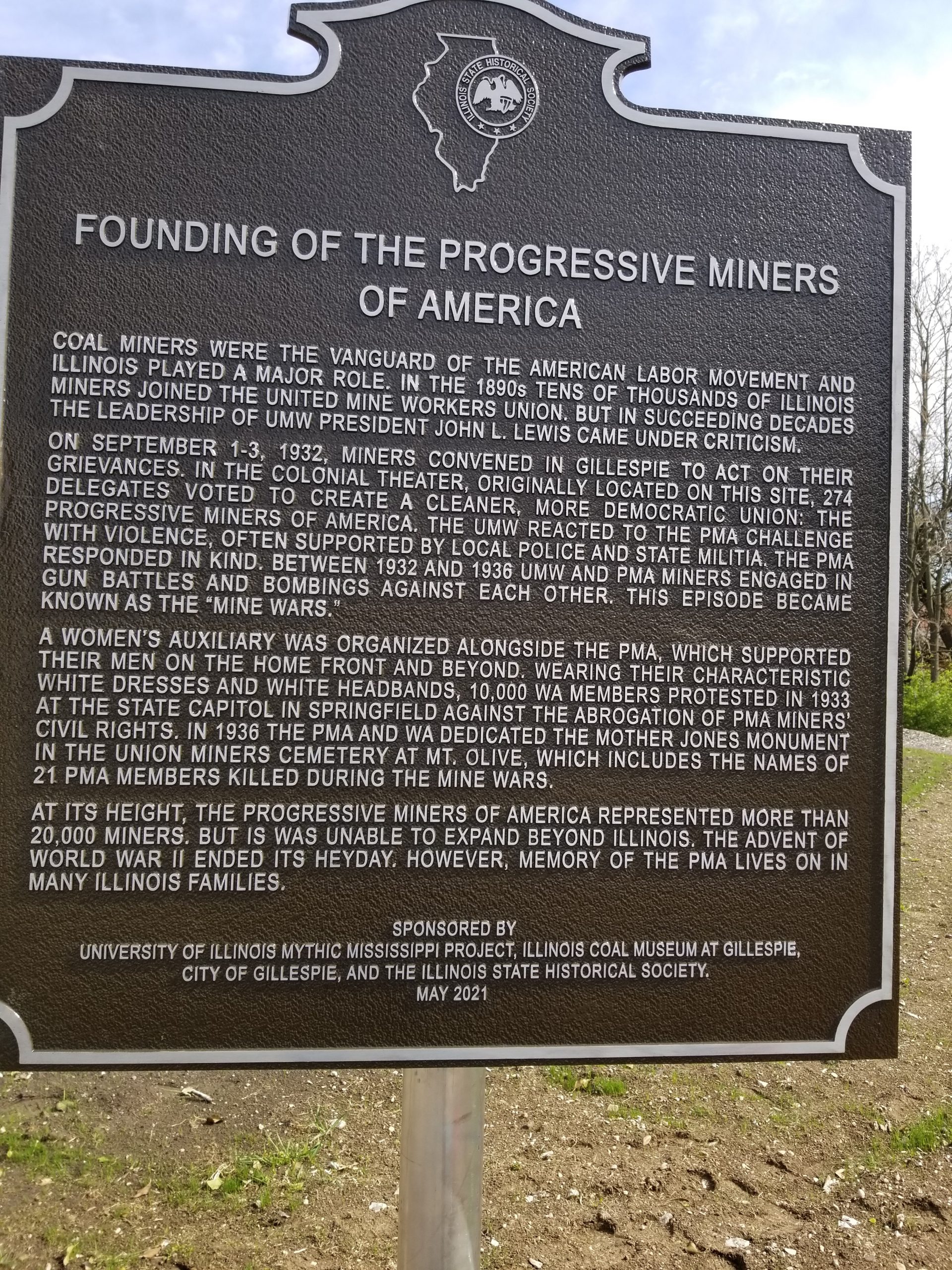

The Progressives were formed on September 3, 1932 following a convention (see image below) held in the old Theatre Colonial in Gillespie (see image here: http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/22625)  photo: IllinoisLaborHistory.org

photo: IllinoisLaborHistory.org

marker erected by the Mythic Mississippi Project in Gillespie, IL, honoring the PMA founding.

It is important to remember that Mother Jones died in 1930, before the Progressive Miners of America (PMA, also called Progressive Mine Workers of America, PMWA) split from the UMW. Elliott Gorn, author of the definitive biography of Mother Jones (Mother Jones. The Most Dangerous Woman in America, 2001) argues that she “still nurtured rebellion even after her death” (p. 297). She certainly was not enamored of John Lewis, President of the UMW. But she also had demonstrated a driving concern to keep the miners together in a united front rather than fragment as was happening in the Rocky Mountain area in 1916. In contrast and as speculation, we think that had General Bradley been alive he would have actively fomented the schism.

The split occurred because the southern Illinois miners were aggrieved that John Lewis had agreed to a 20% pay cut in his negotiation with mine owners and they were unhappy with his leadership style. Already the most radical coal miners in the nation, many southern Illinois miners joined the breakaway group. The convention’s 273 delegates claimed to represent 40,000 miners. They certainly spoke for some 15,000 miners who came to Gillespie and who, en route, faced off against the police (the long-term enemy of union men seeking redress) as well as members of the UMW.

A Women’s Auxiliary was created at the formation of the Progressives’ new union. The role of the WA was extraordinary in the PMA. For example, on January 26, 1933 over ten thousand women congregated in front of the Capitol in Springfield to protest violence against miners and demand an end to civil rights violations. Led by Agnes Burns Wieck (President of the Women’s Auxiliary of the PMA) the women wore white dresses and white headbands, except for the 54 widows of the miners lost in the recent (Christmas Eve, 1932) disaster at Moweaqua, who wore black. Descendants and adherents to the Women’s Auxiliary honor the PMA and Mother Jones every year at the Union Miners Cemetery in Mt Olive.  Another key figure in the Women’s Auxiliary was Katie DeRorre, an Italian immigrant who initiated exceptional social action by organizing soup kitchens for striking miners and their families as well as pioneering the integration of African American and White mining families. Joann Condellone, who you see above carrying the WA banner, relates the history of Katie DeRorre in this video: https://mediaspace.illinois.edu/media/t/1_j5ligw4f

Another key figure in the Women’s Auxiliary was Katie DeRorre, an Italian immigrant who initiated exceptional social action by organizing soup kitchens for striking miners and their families as well as pioneering the integration of African American and White mining families. Joann Condellone, who you see above carrying the WA banner, relates the history of Katie DeRorre in this video: https://mediaspace.illinois.edu/media/t/1_j5ligw4f

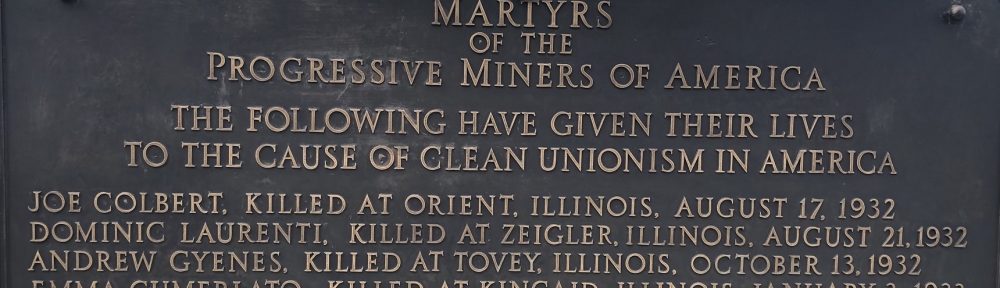

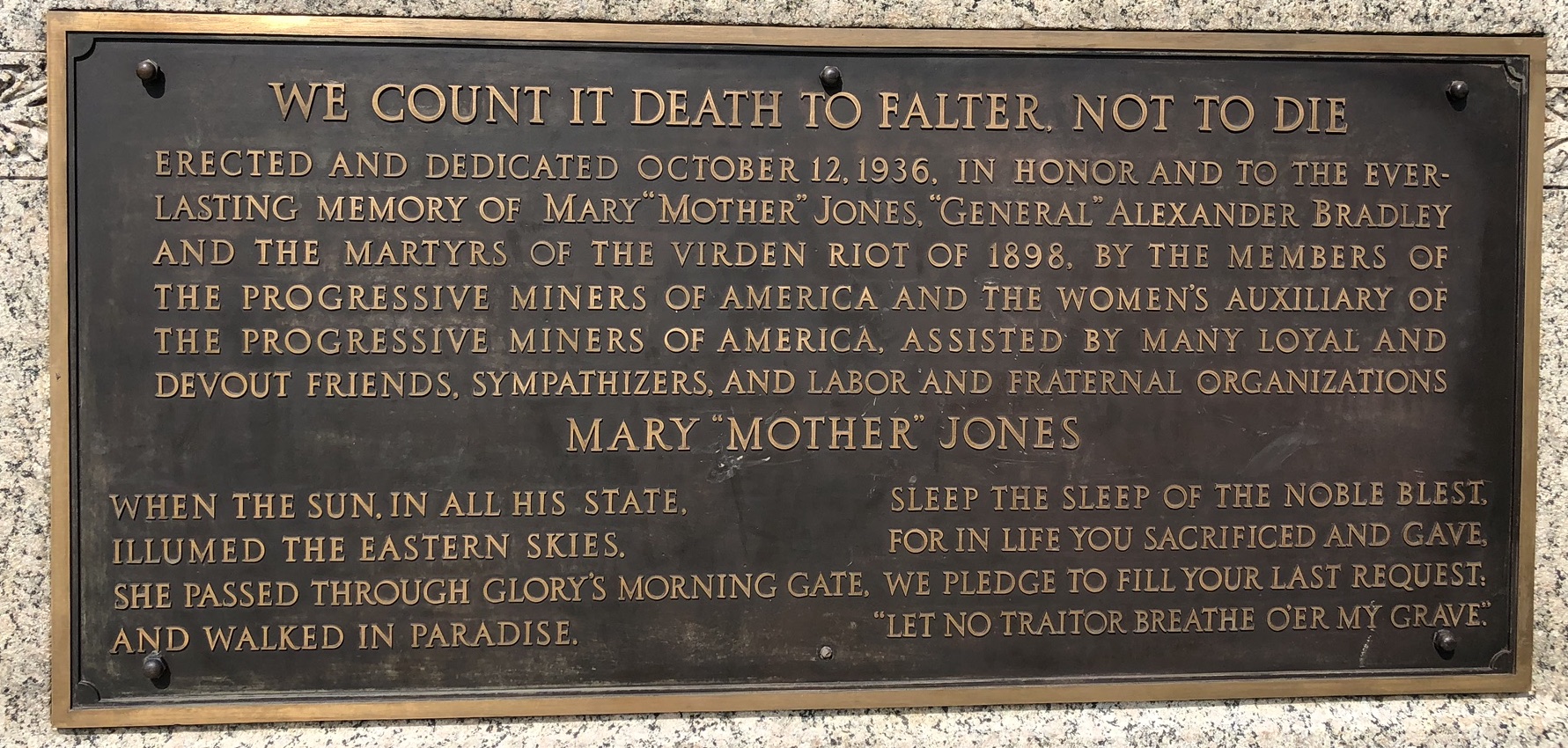

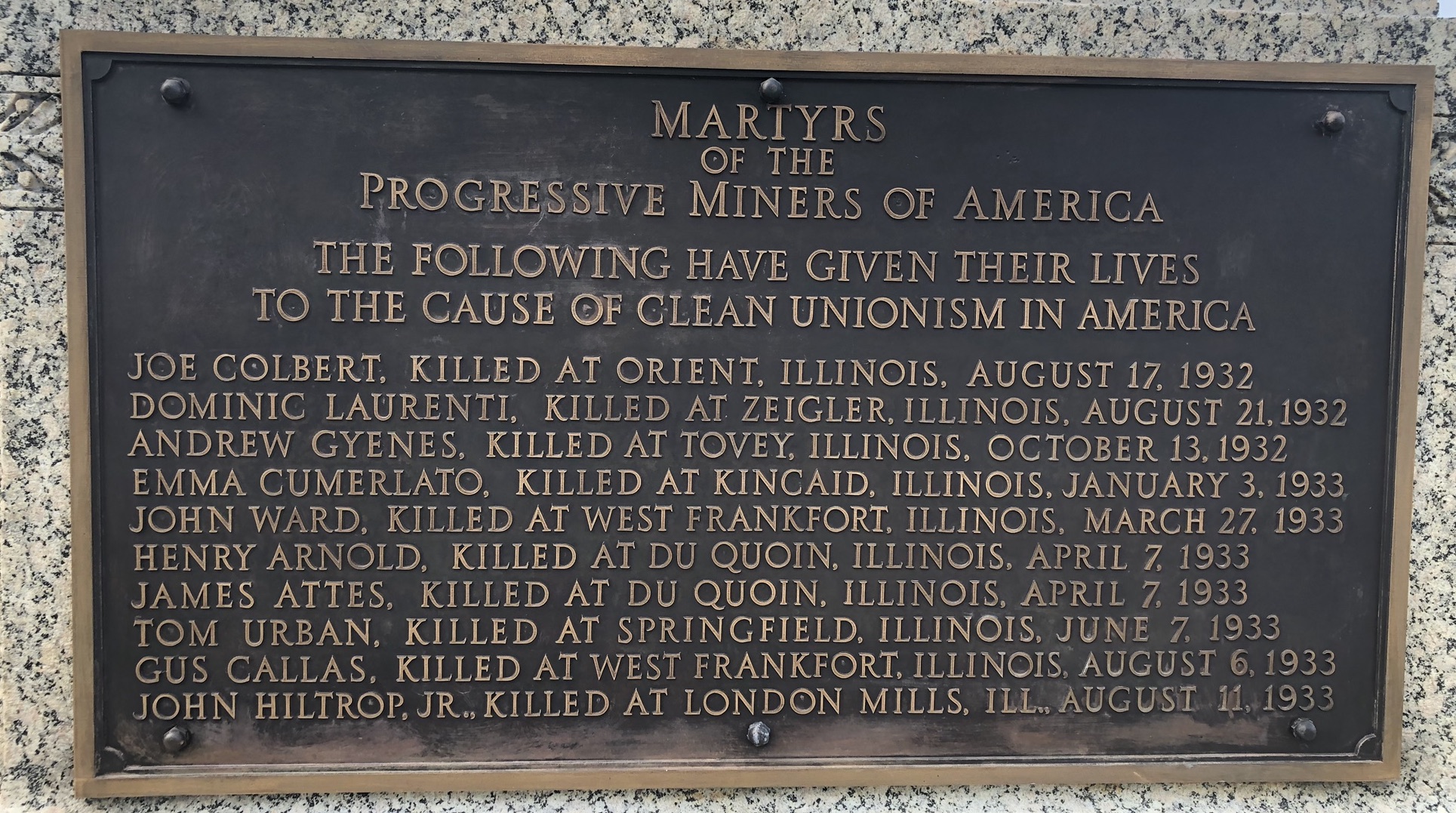

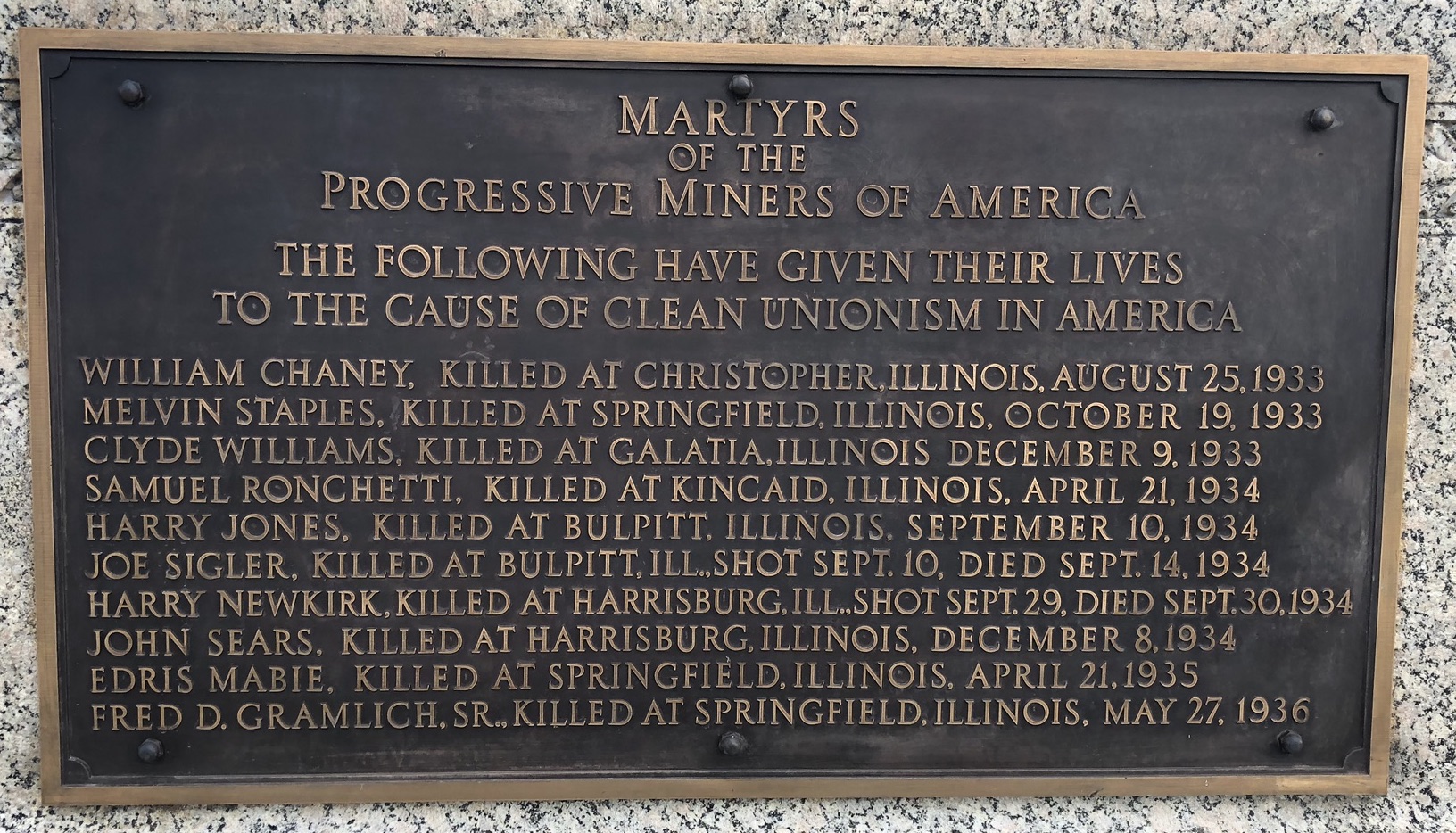

In 1936, soon after the formation of the PMA, the Progressives raised the money to build the grand memorial to Mother Jones in Mt Olive’s Union Miners Cemetery that also recognizes General Bradley and three miners who fell in the Battle of Virden. Importantly, that monument also honors the PMW’s martyrs to “clean unionism” as we see on the plaques below. For these are some of the PMA members who fell in the extreme violence across the southern Illinois coalfields from 1932 to 1936, known as the Illinois Coal Wars or Illinois Mine Wars. Kevin Corley, a history teacher in Christian County, has written a novel of historical fiction about the mine wars using his first-hand experience with the descendants of the events as well as material in the archives of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. The book is called Throw Out the Water (Hardball Press, 2016). We especially refer the reader to SangamonLink’s “coal miner union war, 1932-1937” which has an excellent summary as well as important references: https://sangamoncountyhistory.org/wp/?p=3316

Fifty thousand people attended the inauguration of the memorial which was a rousing tribute to Mother Jones and a vociferous condemnation of the UMW under John Lewis.

We have been told that the Northern Italians of Benld were very prominent in the leadership of the Progressives. We note that the premise of Kevin Corley’s Throw Out the Water (see above) is that two Italian-American brothers align with the two different unions: the UMW and the PMA.

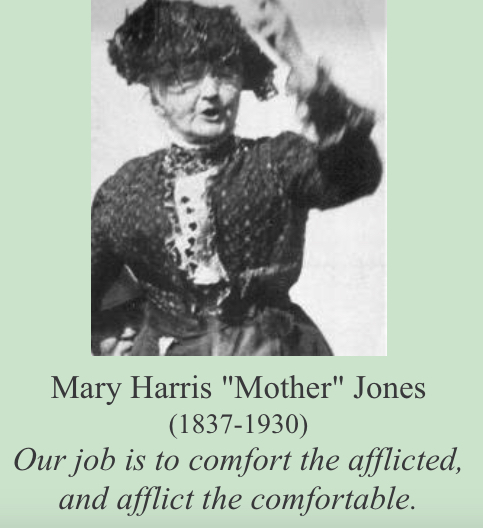

MOTHER JONES

We referred to Mother Jones above and we feature her on the Mt Olive web page because of her burial in the Union Miners Cemetery. Here we want to emphasize that in addition to her passionate advocacy for coal miners, she was devoted to the cause of labor and unionization in all professions/industries. An excellent biography by Elliott J. Gorn called Mother Jones. The Most Dangerous Woman in America (Hill and Wang, 2001) and, admirably, a book written for young readers called Mother Jones. Fierce Fighter for Workers’ Rights by Judith Pinkerton Josephson (Lerner, 1997) provide excellent summaries of the full extent of her activism. (credit: Friday’s Labor Folklore)

(credit: Friday’s Labor Folklore)

MEMORY IN OAK RIDGE CEMETERY, SPRINGFIELD Union Miners Cemetery in Mt Olive is the most obvious landscape of the labor movement in Illinois having been born of the Battle of Virden. Not all victims were buried in Mt. Olive, however. And, most notably, an unexpected hero of the Battle of Virden, was Governor John Riley Tanner (1897-1901). Riley was esteemed by the miners at Virden and in other battles in the state because he reined in or attempted to restrict the mine owners’ use of private armed militias against the miners and he played with an even hand, also encouraging peaceful actions by the miners. He died young and was buried in Oak Ridge Cemetery where Abraham Lincoln already lay. Labor unions made donations to help build his grand mausoleum. The location, between the cemetery’s main entrance and the Lincoln Tomb, makes the Tanner monument one of the most visible memorials at Oak Ridge. Moreover, it was designed by Tiffany of New York and built by Culver Construction of Springfield. It was dedicated on May 30, 1908. At the ceremony was W. D. Ryan, the Secretary-Treasurer of the United Mine Workers.

source: Sangamon Link, https://sangamoncountyhistory.org/wp/?p=9094 (used with permission)

source: Sangamon Link, https://sangamoncountyhistory.org/wp/?p=9094 (used with permission)

WHAT DO FORMER COAL TOWNS REMEMBER AND HONOR? While memorials to miners lost in an underground disaster are expectable in a country like ours that has a culture of physical remembrance and civic action, the more interesting issue is when towns deliberately forget or consciously omit a past that is difficult, disturbing, dissonant. It’s a different matter in Benld, which does not deploy its gangster and raucous history for tourism because of some residual embarrassment amongst the older population, leaving the opportunity to a clever entrepreneur. But what about events of fundamental national significance, such as the coal mine wars that revealed and exploited the vast race problem in our country and whose representation on a town landscape today would continue to remind us of it? Thus, it is fascinating that Pana and Carterville do not have memorials to their fraught labor history whereas Virden prominently displays the Battle of Virden on a memorial in the town square. And in Virden there is a wall mural in whose middle is the black-and-white image of the infrastructure buildings of the Chicago-Virden Coal Company and the wood stockade they built during the Battle of Viden.  portion of Virden wall mural

portion of Virden wall mural

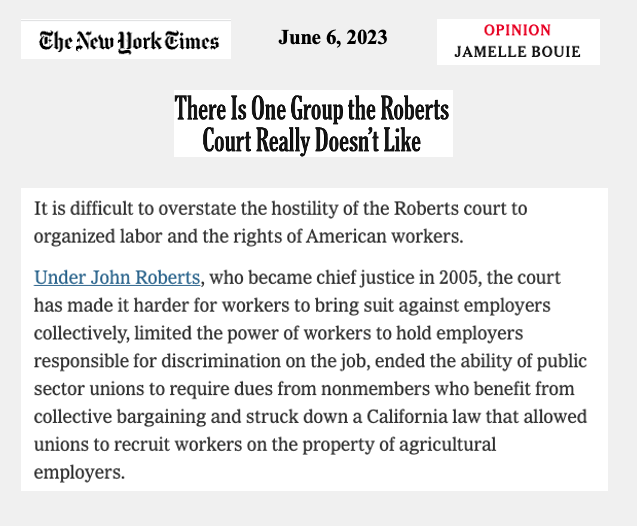

UNIONISM WITHOUT THE COAL MINES

Most of Illinois’ coal mines are closed. Yet former coal miners in towns whose livelihoods once was coal remain passionate about their life experience as miners and devoted to the United Mine Workers of America union that still fights for promised pension benefits and health care. We gain insight into UMW in this rousing speech in defense of all unions by the UMW’s president, Cecil Roberts, in this speech given in Mt Olive in 2018. CLICK ON THE LINK: https://mediaspace.illinois.edu/media/t/1_snvhz7ik

Also in support of labor unions – which was the driving passion of Mother Jones – watch this national explanation of why all unions matter today: http://www.ibew.org/media-center/Video/Sen-Kamala-Harris-on-Why-Unions-Matter

We thank Nick Krumwiede of Mt Olive for sharing with us the beautiful lyrics of his original song, “Price of Coal”, which is about the Battle of Virden: (sound is coming soon)

(sound is coming soon)

As the train whistle blows, the shots they ring out

The echo hits me with fear, dread and doubt

Five hundred shots, with forty-five men down

Tell me how did you come to mine in this town?

D’ya have family here, or are you simply just mad

To align with those dirty and traitorous scabs?

I work my whole life, yet here I lay on the ground

Tell me how did you come to mine in this town?

Sheriff Davenport wired 100 were killed

To the governor: send troops, lest more blood be spilled

My deputies will stand with the miners for now

Tell me how did you come to mine in this town?

With 11 lives lost and 34 more hurt

And Davenport’s men being led off from work

Sheriff cried to convict these criminals of coal

Who ordered these men to mine for their souls

A day of riot and bloodshed, did we expect any less?

When the rich must get richer, they push us to test

Our pain and our suffering on deaf ears they fall

Then they send in the scabs to end the cash-stall

I will miss my brothers and sisters of war

But my love and my family I will miss most of all

For money and greed, my life shall end now

Tell me how did you come to mine in this town?

REFERENCES

Collinsville Historical Museum: original union meetings notes of the Progressives in Collinsville.

Oblinger, Carl D. Divided Kingdom. Work, Community and the Mining Wars in the Central Illinois Coal Fields During the Great Depression. Second Edition, Illinois State Historical Society, 2004).

Sangamon Link. “Coal miner union war, 1932-37”. November 26, 2013. https://sangamoncountyhistory.org/wp/?p=3316