Virden is quiet town only 35 minutes south of Springfield. It has a very pretty town square surrounded by a lovely late 19th-early 20th century streetscape. The center of the square is occupied by a large memorial honoring the soldiers and sailors who fought in World War I.

Virden is quiet town only 35 minutes south of Springfield. It has a very pretty town square surrounded by a lovely late 19th-early 20th century streetscape. The center of the square is occupied by a large memorial honoring the soldiers and sailors who fought in World War I.

And a smaller marker honors those who fought in wars after WWII.

And a smaller marker honors those who fought in wars after WWII.

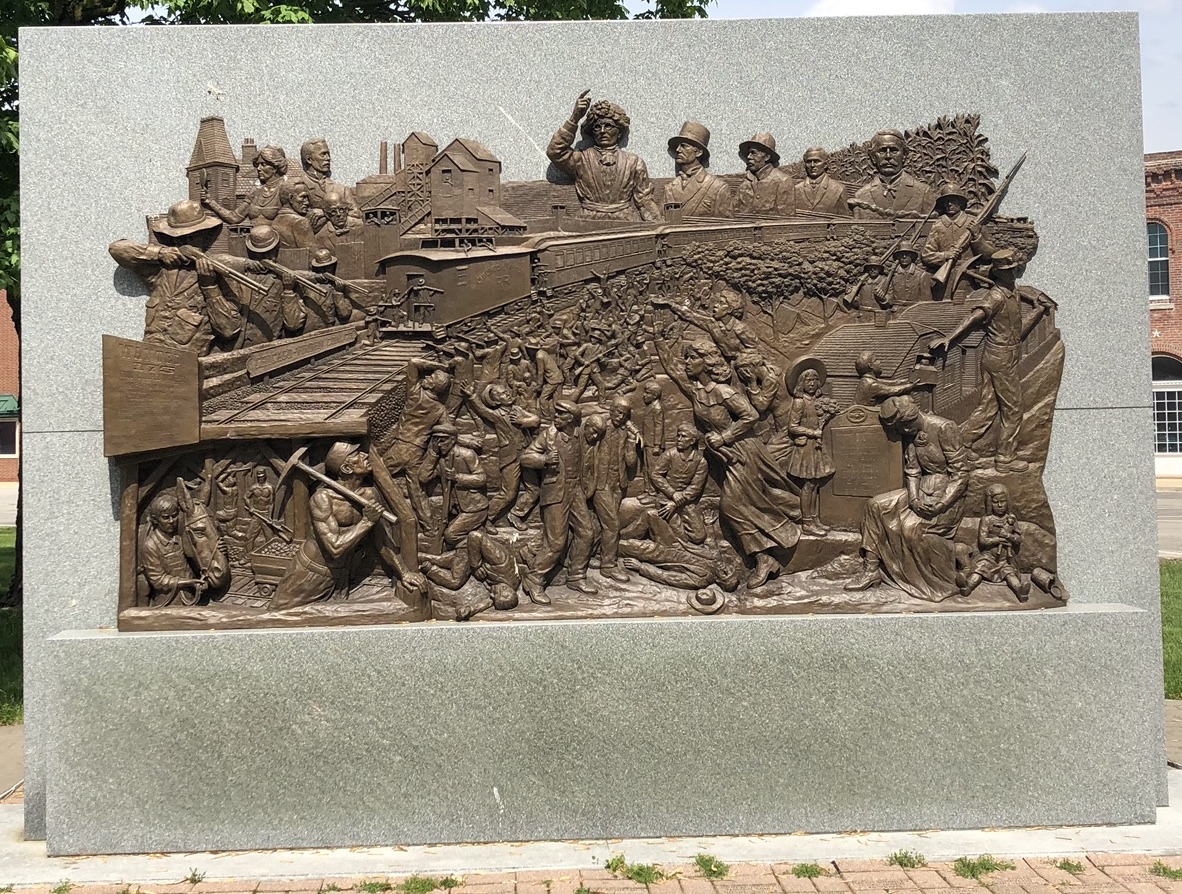

On another side of the square (below) is the memorial for a different conflict — one that was not international but local, although within a larger national context. That memorial honors the coal miners killed in the Battle of Virden in 1898, for. today’s sleepy Virden was once the epicenter of a violent labor struggle.

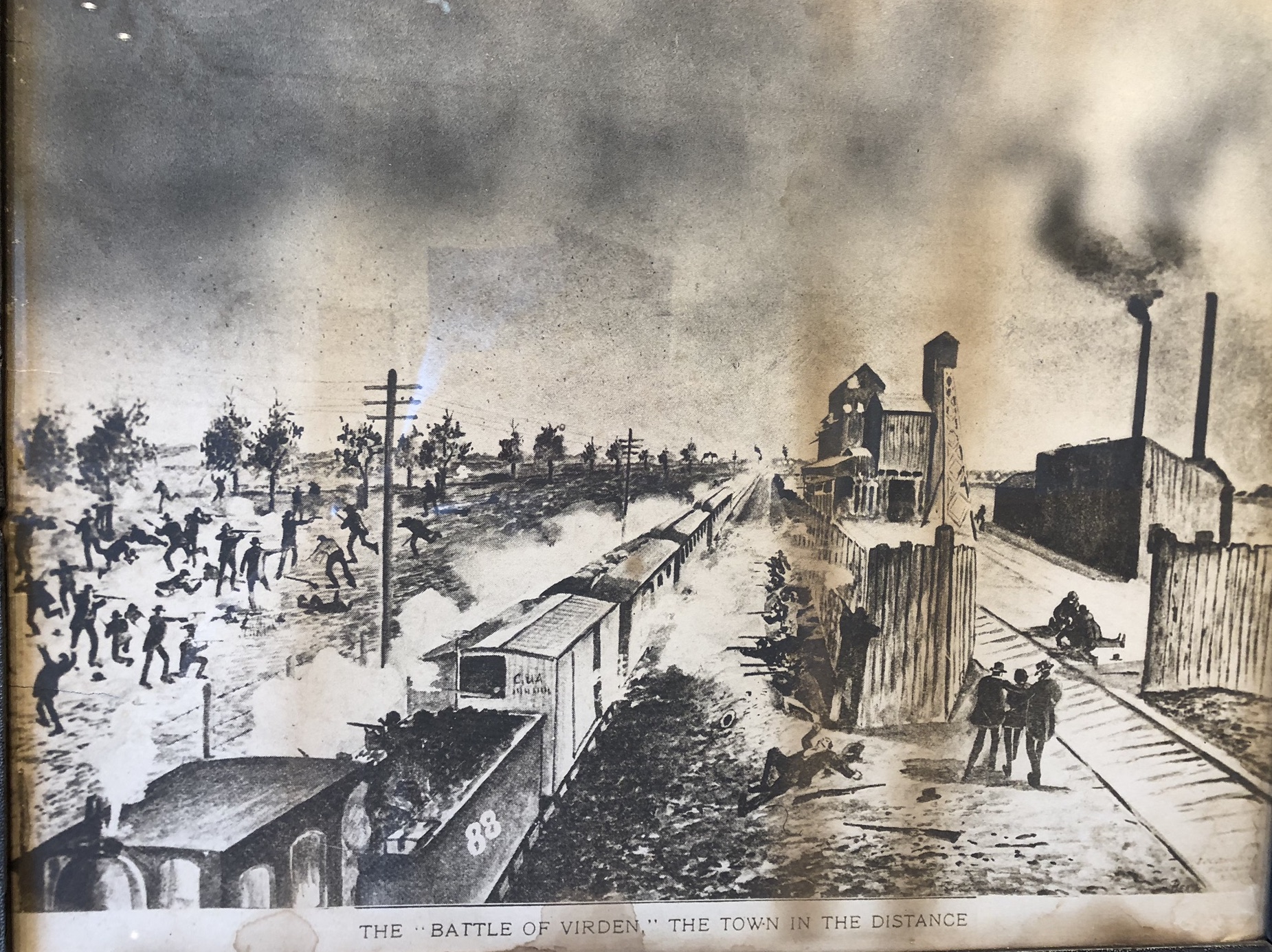

The memorial is a vivid portrayal of the action on that dramatic day: October 12, 1898.

Above: Interestingly, it features Mother Jones in the center at the top, even though she was not involved in this battle.

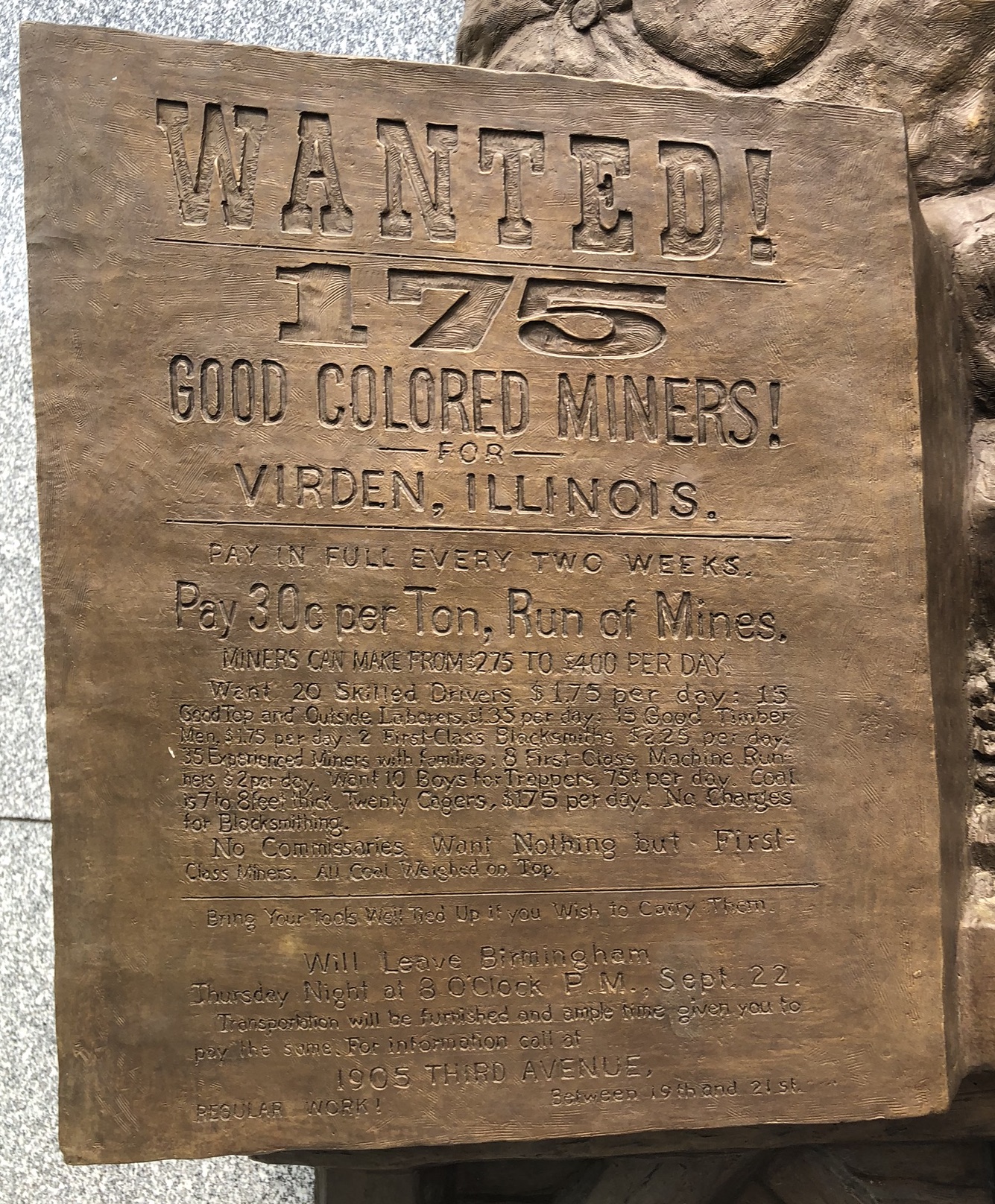

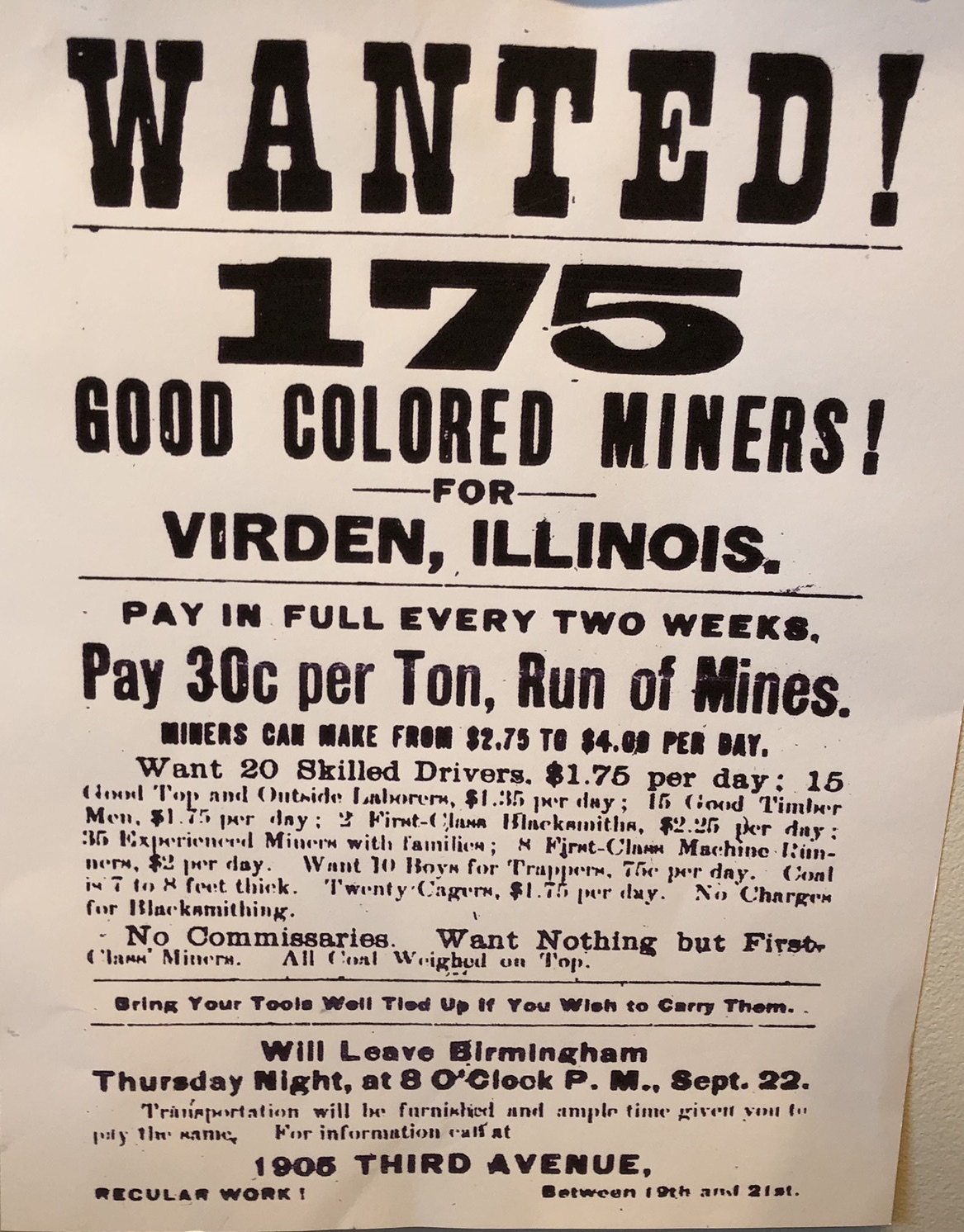

Below: And it clearly represents the poster that circulated in Alabama to recruit “175 good colored miners” (far left side of image).

THE BATTLE OF VIRDEN  Virden sits atop a rich deposit of coal and that coal became economically viable with the creation of efficient rail transportation here and throughout the state. The railroad owners and the coal mine owners operated “hand in glove” to exploit labor.

Virden sits atop a rich deposit of coal and that coal became economically viable with the creation of efficient rail transportation here and throughout the state. The railroad owners and the coal mine owners operated “hand in glove” to exploit labor.

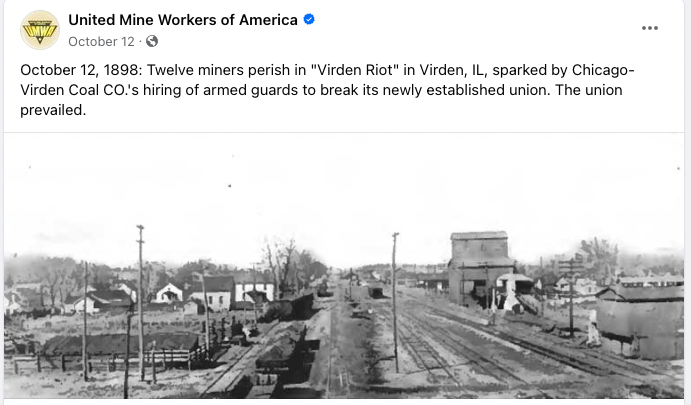

The “Battle of Virden” resulted in the deaths of 7 miners (and 40 wounded miners) and 5 guards as well as a company railroad employee; 4 others were wounded. The event had lasting significance for Illinois coal mining, its labor organization and the history of the labor movement in the United States – see https://mythicmississippi.illinois.edu/coal/labor-heritage

WATCH THE RECORDING OF OUR WEBINAR (DECEMBER 7, 2023): “VICTORY AT VIRDEN”

WATCH VIRDEN NATIVE, JOHN ALEXANDER, EXPLAIN THE BATTLE OF VIRDEN

(our thanks to James Goltz/JASE Media Service for permission to use this video):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8qcBLQL2beg

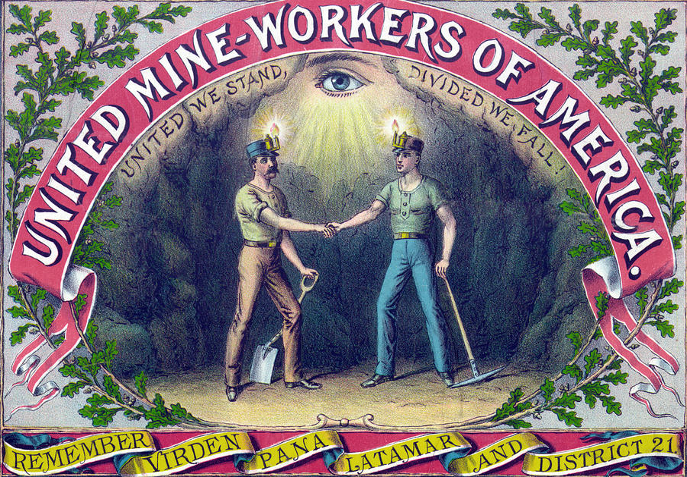

Briefly, the conflict started because the mine owners’ of the Chicago-Virden Coal Company refused to let the Virden miners unionize whereas a nationwide agreement between bituminous coal operators and the United Mine Workers had recently been reached and its wage scale should have applied everywhere. In response to the Virden miners’ strike the company brought in African American miners from Alabama to scab. Not only were the miners aggrieved at the mine owners, they were infuriated by the African Americans. Those poor Blacks were recruited unaware of the lesser wage they would be paid and the labor conflict awaiting them up north (see poster below – on display in the Mother Jones Museum, Mt. Olive).

The company’s first attempt to import black strikebreakers failed in September, when union miners commandeered the train bringing the Alabamans to Virden and then convinced their would-be replacements to return home.

Next the company had a stockade built around the mine and hired fifty guards, many of them former Chicago police officers, to defend the train, the mine and the strikebreaking workers.

The dastardly company also appealed to Gov. John Tanner to call in state militia to escort the strikebreakers into the stockade. But Tanner, with midterm elections a month away and public sentiment on the miners’ side, refused.

As explained by historian David Markwell, “The hired guards took their positions along the [stockade] walls. The strking miners stood watch along the tracks awaiting the arrival of the Alabamans. Everyone except the Alabama miners was fully aware of the situation.” Also in place, awaiting the anticipated confrontation, were newspaper reporters from all over the country. Nonetheless, many details of the brief battle remain unclear, including who fired the first shot in anger.

The first exchange of gunfire happened at 12:40 p.m. as a new train carrying Black miners appeared. But seeing danger, the trains sped past the station. One of the armed guards fired in the air and that started a volley of shots, one of which (aimed from inside the stockade) killed a guard for the Chicago & Alton Railroad who was assigned to guard the C&A’s switches.

The leaders of the miners had hoped that the Alabaman strikebreakers would leave the train at the depot, where the union miners planned to try to persuade them to return home. Instead, the train continued toward the mine and the stockade. But when the company’s armed forces saw the large number of strikers, they opened fire. Several men lay dead in the open field and others were so badly injured they soon died.

Photo of framed engraving in the Mother Jones Museum in Mt Olive

Photo of framed engraving in the Mother Jones Museum in Mt Olive

After the battle, Governor Tanner dispatched several militia companies to Virden to disarm both sides. Tanner also ordered the militia not to allow strikebreakers to enter the stockade. The Governor and mine owner blamed each other for the bloodshed.

The significance of the event is huge and was huge right after the massacre (as it is often called) occurred. Unable to employ strikebreakers and unsupported by state officials, the Chicago-Virden Coal Co. capitulated. The mine reopened a month after the battle, paying the new rate. Dr. Markwell concludes that the miners’ success in obtaining the previously negotiated national rate at Virden had implications beyond improving living conditions for miners and their families (such as they were). The outcame gave Illinois a labor-friendly reputation just as demand for coal was expanding, along with opportunities for mine jobs. For Dr. Markwell, the Battle of Virden “marks the beginning of the end of the feudalism that characterized the Illinois coalfields and late nineteenth-century industrialism in general.”

The African American miners, who had come with their wives and children, were redirected to Springfield. The coal company refused to protect or provide for them. That created what the Illinois State Register called “a pitiable and shameful spectacle.” Historian David Markwell concluded that there were 57 men, 15 women and five children in the African American group. The nascent union seems to have persuaded some of them to return home at the union’s expense. The remainder finally embarked on October 14 on a special train for St. Louis. Springfield businesses raised $100 to hire the train, and leftover funds were given to its passengers – 50 cents to each man and $1 to each woman. At the order of the mayor, Police Chief H.S. Castles provided coffee and 300 sandwiches for the trip. Dr. Markwell says that some found employment in St. Louis while others made it back to Birmingham.

BUT WHAT ABOUT THE DEAD MINERS?

Notwithstanding the labor victory for the miners, Virden was still a “company town” and feelings against the miners ran high – so high that the deceased coal miners were denied burial in Virden. Four of those miners were from Mt. Olive.

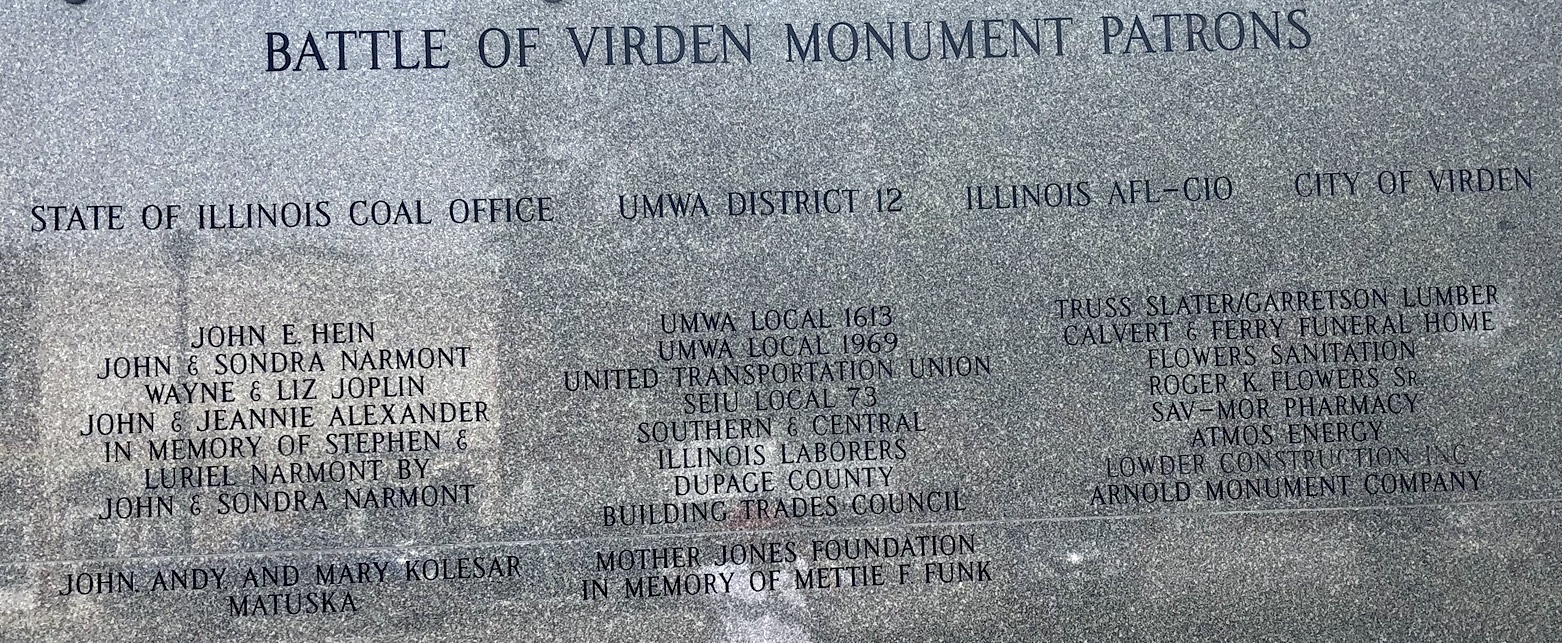

BATTLE OF VIRDEN MEMORIAL IN THE TOWN SQUARE

The Battle of Virden Monument, erected on the town square in 2006, lists the eight dead miners: One of the most interesting aspects of any memorial is where to put it, who decides, and, of course, who designs it. The “space of memory” is often contested. It has to be won in what are often acrimonious discussions. Even the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C. honoring the heroic dead in what is overwhelmingly regarded as a necessary war and “a good war” faced a lengthy battle of its own to achieve a place on the National Mall. Thus, it is very interesting to consider that the World War I Memorial has pride of place in Virden and only belatedly was the Virden Memorial able to obtain approval and funding.  Back of the monument. Left column: local individuals. Middle column: organized labor. Right column: local businesses In addition to this major sponsorship, further contributions were received from those individuals whose names appear on the bricks of the pavement surrounding the monument. Some merely have the name of the donor. Some say they are in memory of family member. Sometimes a commemorated family member had a connection with mining. Some identify as community organizations or shops. And a few make overtly activist statements: “Lest we never forge those gave so much”; “An injury to one is an injury to all”.

Back of the monument. Left column: local individuals. Middle column: organized labor. Right column: local businesses In addition to this major sponsorship, further contributions were received from those individuals whose names appear on the bricks of the pavement surrounding the monument. Some merely have the name of the donor. Some say they are in memory of family member. Sometimes a commemorated family member had a connection with mining. Some identify as community organizations or shops. And a few make overtly activist statements: “Lest we never forge those gave so much”; “An injury to one is an injury to all”.

IRONIC AFTERMATH In downstate Illinois, many towns or private sponsors in them have commissioned the painting of murals on the sides of their red brick buildings. Virden is one such town as we see in the banner image of this webpage. The mural (19′ x 50′) is on the side of the Sav-Mor Pharmacy building. The mural was completed on August 12, 2018. Interestingly, the most significant event in Virden’s history – in our opinion – is not represented on the mural: the Battle of Virden. Rather, the mural emphasizes other, pleasant aspects of Virden’s history. The mural can be closely examined at this website: https://www.virdenmural.com/mural-sketch.html The mural was a citizen initiative and it shows that group’s vision of Virden’s past, a past with no negative history. (A further note about the brick mural: a fuil-length rendering of Sarah Newby Hall appears in the center. She was born a slave and lived through Emancipation till her death in 1936. Virden honors her, explaining on the mural’s website that she was the town’s baby sitter and was respected by all. Research is needed.)

THE ISSUE OF SCABS FROM ALABAMA IS PLAYING OUT TODAY (April 2021) !

REFERENCES Feurer, Rosemary. “Remember Virden. The Coal Mine Wars of 1898-1900.” Online resource: https://www.lib.niu.edu/2006/iht1320610.html

Markwell, David. “A Turning Point: The Lasting Impact of the Virden Mine Riot,” Illinois State Historical Society (Fall 1986/Winter 1987)

Sangamon Link: “The Battle of Virden, 1898”, published November 13, 2016

https://sangamoncountyhistory.org/wp/?p=9094 Quoted and paraphrased. Used with permission.