On August 4, 2023 Governor J. G. Pritzker signed a law requiring Illinois public schools to teach Native American history. As explained by UIUC Department of History’s Professor Rosalyn LaPier, the new law will help students learn about the Indigenous people who originally occupied this land as well as recognizing that there are contemporary Native American communities in the state. Read the article about this law here: https://news.illinois.edu/view/6367/1925176613

The University of Illinois is aware that it sits on what was once native land, occupied by multiple Indigenous peoples including the Peoria, Kaskaskia, Peankashaw, Wea, Miami, Mascoutin, Odawa, Sauk, Mesquaki, Kickapoo, Ojibwe, Chickasaw and Potawatomi. Some of these names – such as Peoria and Kaskaskia – still exist on the landscape of the state of Illinois.

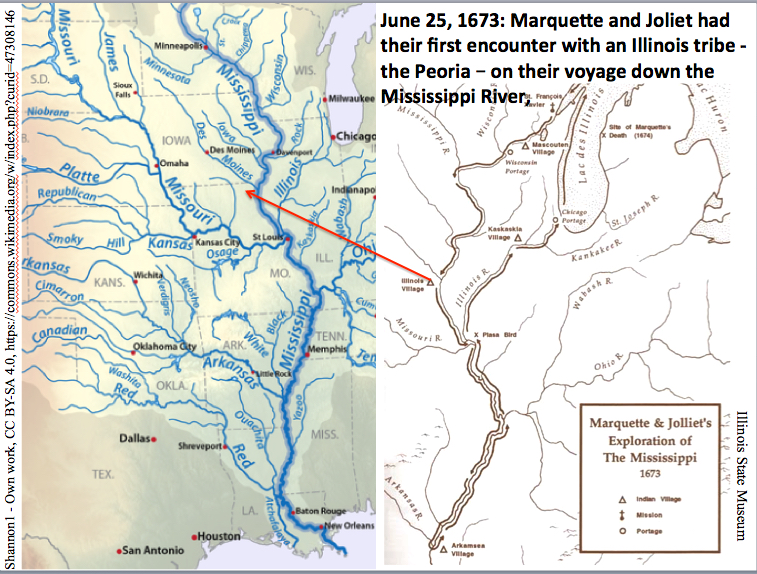

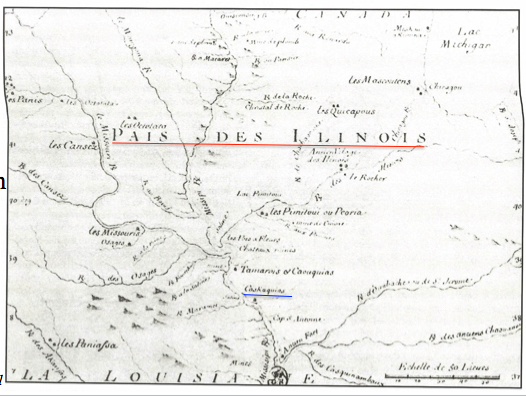

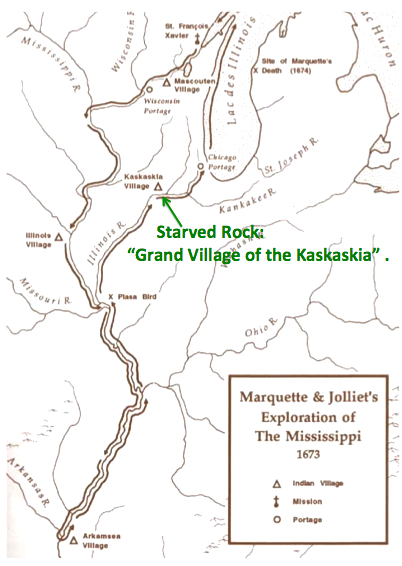

The native people encountered by the French, who were the first Europeans to have contact with them, were about a dozen tribes who spoke an Algonquian language. They called themselves Illinois as the French heard them, starting with Marquette and Joliet in their exploration of the Pays des Illinois in 1673-1674.

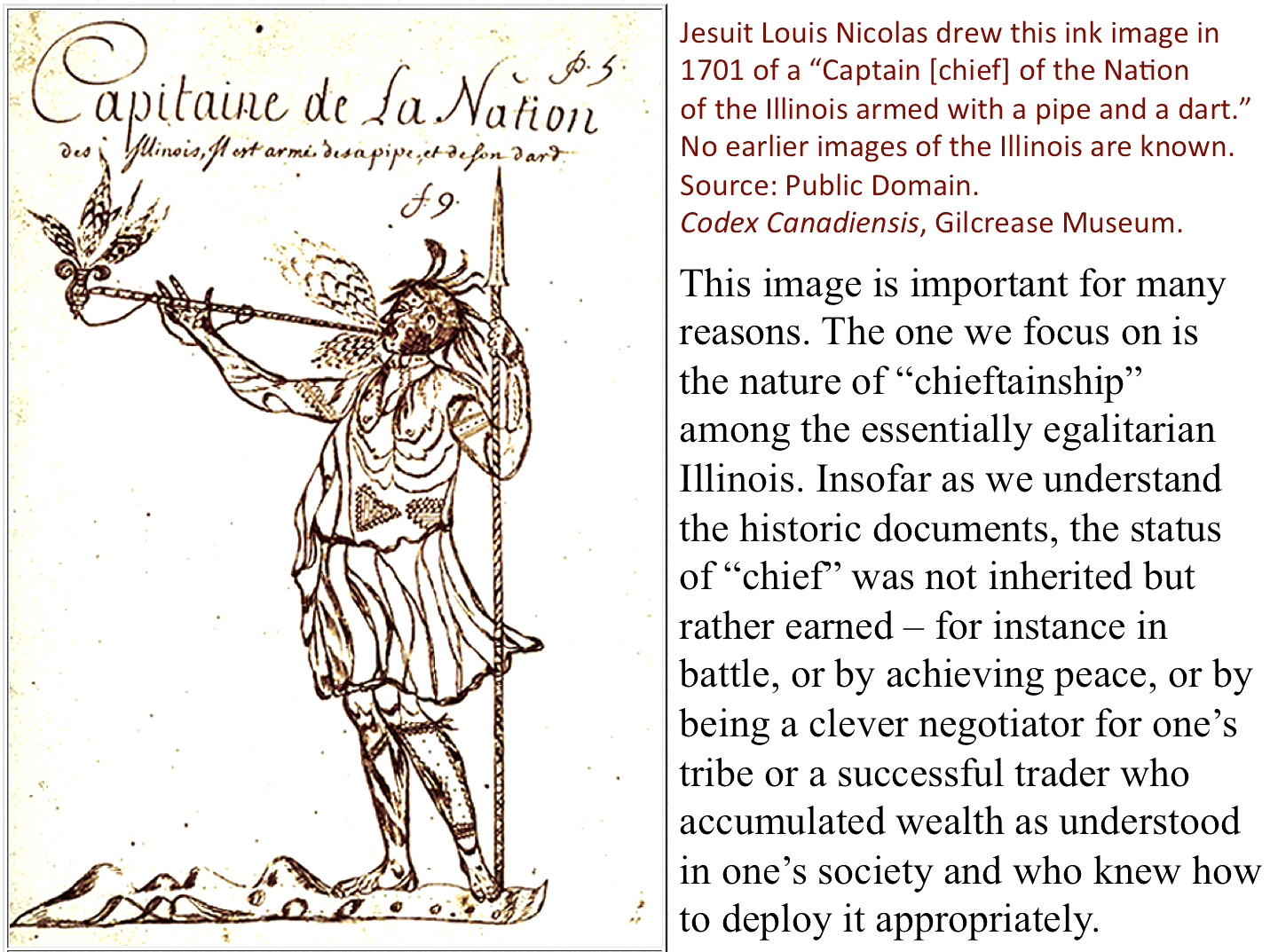

French traders were moving around the native landscape before the Jesuits arrived, but they didn’t keep records. By the time the Jesuits were making first contact, the Illinois were already involved in trade networks that brought them European glass beads – a status item as an exotic good – and they were interested in obtaining useful metal hatchets, knives, firearms and other implements from the French.

Most of the literature refers to these tribes as having been a “confederacy”.  At contact these Illinois people may have numbered between 10,000-15,000. They lived between other Indian groups, such as the Sioux to the west and the Iroquois to the east. The Iroquois of New York were extremely aggressive. In the 1650s they began a campaign of terror around the Algonquian Great Lakes, prompted in part by their need for beaver pelts for the fur trade with Europe. They attacked the Illinois as well, who counter-attacked and then the Illinois attacked the Sauk and Fox in the 1660s as they and other tribes fled from the Iroquois and entered Illinois land. The history of the Illinois is one of attacked-attack and attack-attacked. And that history is imbricated in the global politics of European colonialism in “the New World” with the Dutch and British supporting the Iroquois and the French supporting the Algonquian tribes.

At contact these Illinois people may have numbered between 10,000-15,000. They lived between other Indian groups, such as the Sioux to the west and the Iroquois to the east. The Iroquois of New York were extremely aggressive. In the 1650s they began a campaign of terror around the Algonquian Great Lakes, prompted in part by their need for beaver pelts for the fur trade with Europe. They attacked the Illinois as well, who counter-attacked and then the Illinois attacked the Sauk and Fox in the 1660s as they and other tribes fled from the Iroquois and entered Illinois land. The history of the Illinois is one of attacked-attack and attack-attacked. And that history is imbricated in the global politics of European colonialism in “the New World” with the Dutch and British supporting the Iroquois and the French supporting the Algonquian tribes.

France began its North American enterprise in 1534 with Jacques Cartier’s explorations, sponsored by King François I. But his attempts to create colonies and those of subsequent French who sought to install themselves on the native landscape quickly failed. However, at the start of the 17th century and throughout the 1600s, French prior experience, persistence, cultural diplomacy with the Indians and shared interests succeeded in creating a vast French territory from Quebec, across the Great Lakes and down the Mississippi to New Orleans.

France began its North American enterprise in 1534 with Jacques Cartier’s explorations, sponsored by King François I. But his attempts to create colonies and those of subsequent French who sought to install themselves on the native landscape quickly failed. However, at the start of the 17th century and throughout the 1600s, French prior experience, persistence, cultural diplomacy with the Indians and shared interests succeeded in creating a vast French territory from Quebec, across the Great Lakes and down the Mississippi to New Orleans.

The Illinois people were mobile with home villages and seasonal camps, particularly for the bison hunt. The various Illinois tribes aggregated and disaggregated on the landscape as required by their livelihood as well as intra- and inter-group dynamics.

Having traversed much of the Mississippi River southwards, on their return trip, Marquette and Joliet left the Mississippi River and ascended the Illinois River. They found a “grand village” of Kaskaskia Indians living in “74 cabins” (which we should understand as long houses). Marquette returned to the great settlement on Easter, 1675, to establish the Immaculate Conception mission. Soon after the village grew in size to “more than 350 cabins.” In 1677 it was observed to be multi-tribal and in 1678 it was estimated to have “400 or 500 cabins, each with 5 or 6 families” (see Temple, reference below). European trade goods were in circulation here and in other villages.

In 1947 archaeologists identified the site of Grand Village of the Kaskaskia! In the academic archaeological literature that site is known as the Zimmerman Site. For an introduction to the exciting excavations and their results see: http://www.museum.state.il.us/muslink/nat_amer/post/htmls/arch_zim.html

In 1947 archaeologists identified the site of Grand Village of the Kaskaskia! In the academic archaeological literature that site is known as the Zimmerman Site. For an introduction to the exciting excavations and their results see: http://www.museum.state.il.us/muslink/nat_amer/post/htmls/arch_zim.html

Marquette reported that the Kaskaskia were receptive to Catholicism. Indeed, they were the most readily converted of all the Illinois tribes for which there is historical information. In the late 1600s (ca. 1681-1700) with the Indigenous landscape having been especially disturbed by the Iroquois, some (number unknown but appears to have been significant) Kaskaskia moved to today’s Peoria area (Pimitéoui) with their Jesuit priests and established themselves where the French already had built forts and other (non-competing) tribes were living and there was plentiful game.

Historians concur that the Kaskaskia did not stay long there, nor did they stay long at their next stop: Des Peres (today this would be the south side of Saint Louis at the mouth of the Des Peres River where it enters the Mississippi River) . However, historians differ as to why the Kaskaskia left Pimitéoui although they agree that the other Illinois tribes (Moingwena, Peoria) at Pimitéoui did not accompany them. In 1703 the Kaskaskia and their French priests and the French trappers who had taken Indian wives established themselves on what was a peninsula of land between the Kaskaskia River and the Mississippi River. That settlement became the historic town of Kaskaskia. Again – the Kaskaskia have left their imprint on the toponymy of the state.

WATCH PROFESSOR ROBERT MORRISSEY (Department of History) DISCUSS HIS RESEARCH ON THE INDIANS OF THE ILLINOIS TALL GRASS PRAIRIE: https://mediaspace.illinois.edu/media/t/1_ohf3pdyx?st=0

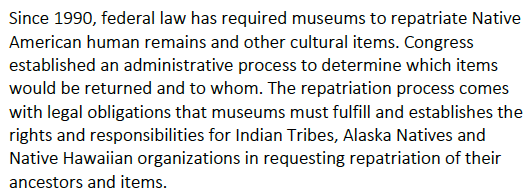

Flash forward to the second half of the twentieth century. In the 1960s in tandem with the civil rights movements among African Americans and the gay population, Native Americans began insisting on their civil rights across several domains. One was unique: they began to complain that the human remains of their ancestors were being improperly and disrespectfully treated in museums and by archaeologists in the field. The outcome of some three decades of protests as well as a significant change in the ethical platform of the Society for American Archaeology was the 1990 Congressional passage of NAGPRA, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

We are pleased to present this interview with the NAGPRA officer of the University of Illinois: Krystiana Krupa.

We are pleased to present this interview with the NAGPRA officer of the University of Illinois: Krystiana Krupa.

Please click on this link to watch the interview: https://mediaspace.illinois.edu/media/t/1_1t3k8ibk

A critical NAGPRA issue in the State of Illinois are the tens of thousands of human remains and sensitive cultural objects of tribal people who were removed from the state in the 19th century. The University of Illinois is working diligently to comply with the letter and spirit of NAGPRA. National Park Service image of boxed human remains illustrates serious ethical dimension of NAGPRA.

National Park Service image of boxed human remains illustrates serious ethical dimension of NAGPRA.

OF TREMENDOUS IMPORTANCE OVERALL:

2007

2007

The preceding discussion was about the Native American history of Illinois, efforts by Native people to claim dignity, and the laudable role of NAGPRA in enhancing Native American rights. We move on to the work of one of Illinois’ premier and most influential archaeologists, Dr. Michael Wiant, the former Director of Dickson Mounds Museums and a previous Interim Director of the Illinois State Museum in Springfield.

Below, you will see the link to one of the three interviews with Dr. Wiant, conducted by the Oral History team of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library on October 19, 2020: HSP-A-L-2020-062. In this interview Dr. Wiant comments on changes in archaeology and future of archaeology in Illinois. https://multimedia.illinois.gov/alplm/Oral_History/Historians_Speak/Wiant_Mic/Wiant_Mic_03.mp3

Below, you will see the link to one of the three interviews with Dr. Wiant, conducted by the Oral History team of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library on October 19, 2020: HSP-A-L-2020-062. In this interview Dr. Wiant comments on changes in archaeology and future of archaeology in Illinois. https://multimedia.illinois.gov/alplm/Oral_History/Historians_Speak/Wiant_Mic/Wiant_Mic_03.mp3