Public history seeks to engage and inform “the public”, from a local community all the way to the nation. Rather than academic history, which is produced by and consumed by scholars, public history has a far broader audience. This is not to say that public history lacks veracity, only that public historians deploy their rigorous training in a more inclusive manner. Some public history projects are designed for a small public from the beginning. Other public history may reach thousands, tens of thousands, even millions of people. Some of the museums comprising the Smithsonian Institution have that reach. And some of the great outdoor historic sites of our country, such as the Gettysburg Battlefield with its interpretation program, has immense numbers of visitors.

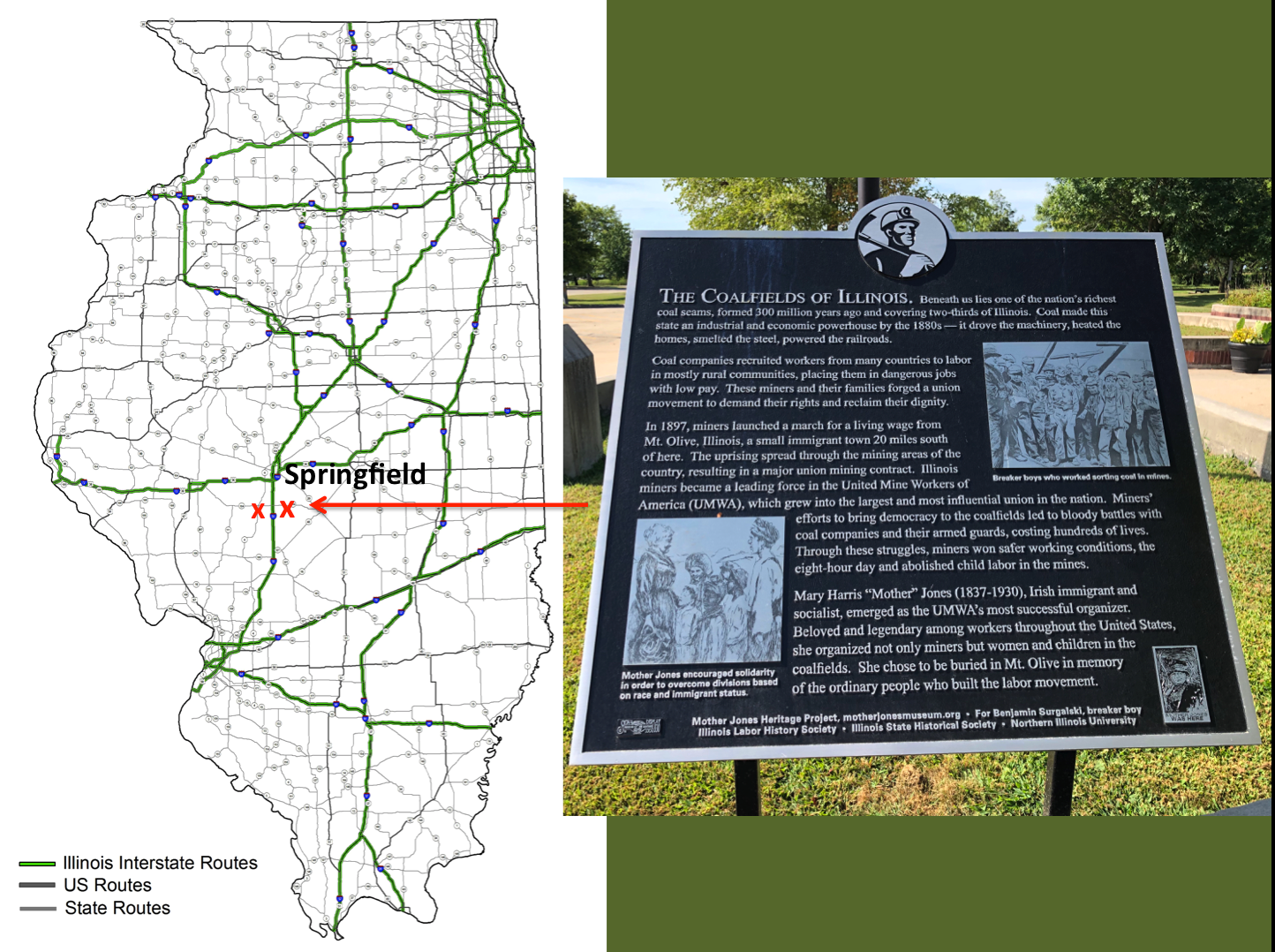

A tremendously innovative public history program is found at a highway rest stop 25 miles south of Springfield on I-55. IDOT (Illinois Department of Transportation). It is the result of the initiative of several educational and professional agencies/institutions. The rest stop is named “Coalfield Rest Area”. Southbound, the rest stop features an explanatory historical marker about the coalfield (below). Northbound, there is a similar sign, that one for Mother Jones. Moreover, inside the rest stop (north and south) there are several didactic panels that expand on the information outside. The potential of the outdoor signs, in particular, to be read by extraordinary numbers of travelers (in-state, out-of=state, foreign) is incalculable. This is public history at its best!

Here we transcribe the information on the “The Coafields of Illinois” sign (above): “Beneath us lies one of the nation’s richest coal seams, formed 300 million years ago and covering two-thirds of Illinois. Coal made this state an industrial and economic powerhouse by the 1880’s – it drove the machines, heated the homes, smelted the steel, powered the railroads. / Coal companies recruited workers from many countries, placing them in dangerous jobs with low pay. These miners and their families forged a union movement to demand their rights and reclaim their dignity. / In 1897, miners launched a march for a living wage from Mt. Olive, Illinois, a small immigrant town 20 miles south of here. The uprising spread through the mining areas of the country, resulting in a major union mining contract. Illinois miners became a leading force in the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), which grew into the largest and most influential union in the nation. Miners’ efforts to bring democracy to the coalfields led to bloody battles with coal companies and their armed guards, costing hundreds of lives. Through these struggles, miners won safer working conditions, the eight-hour day and abolished child labor in the mines. / Mary Harris ‘Mother’ Jones (1837-1930), Irish immigrant and socialist, emerged as the UMWA’s most successful organizer. Beloved and legendary among workers throughout the United States, she organized not only miners but women and children in the coalfields. She chose to be buried in Mt. Olive in memory of the ordinary people who built the labor movement.”

Mother Jones explicitly chose to be buried in Mt. Olive so as to be next to “her boys” – the miners who fought and those who died in the Battle of Virden and who are buried in the Union Miners Cemetery. See our relevant webpages, hyperlinked in blue.