What are memorials? Why are they erected? By whom? Where are they placed? These are some of the key questions that scholars investigate about this widespread phenomenon. And these are questions of tremendous public concern and political and social partisanship in America today.

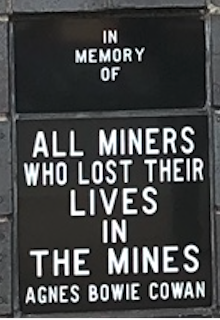

Coal mining was a tremendously dangerous activity and just in terms of our project’s geographical focus, there is no lack of memorials commemorating the lives lost in underground disasters and/or honoring the bravery of all miners. There also are memorials that remember miners who died in violent struggles waged around labor issues.

On this web page we present coal mining memorials downstate. They are listed alphabetically. Starting in Springfield, they can be visited in a one-day loop, though an overnight stay is merited so as to spend the necessary time looking at these sites and considering them.

HERRIN (100 N. 14th Street)

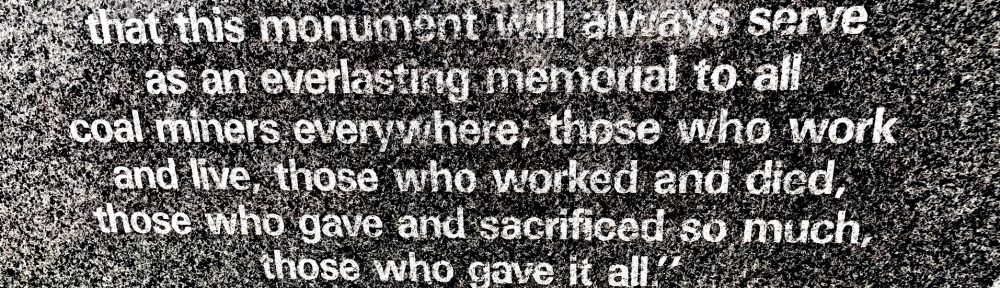

The text of the memorial says: Coal Miners Memorial. In memory of coal miners, who gave so much that future generations may benefit with a better life… They labored, served their country, sacrificed for their families and some lost their lives … We honor and salute them so that they will never be forgotten. Dedicated October 14, 2000

The memorial shows a miner talking affectionately to his little son. The miner appears to be ready to go on his shift, possibly saying goodbye to the boy. Alternatively, he may have returned home.

The plaques on the wall of this memorial are fascinating for what they tell us about Herrin’s mining past in the words of its patrons/donors.

The plaques on the wall of this memorial are fascinating for what they tell us about Herrin’s mining past in the words of its patrons/donors.

We learn that miners had a strong sense of identity based on the mines in which they worked.

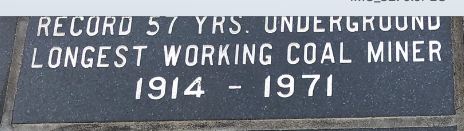

Prof. Silverman unfortunately cut off the name on this plaque when she took this photo, but we see that this man was intensely proud of holding a record for the most years (57) worked underground as a miner.

Prof. Silverman unfortunately cut off the name on this plaque when she took this photo, but we see that this man was intensely proud of holding a record for the most years (57) worked underground as a miner.

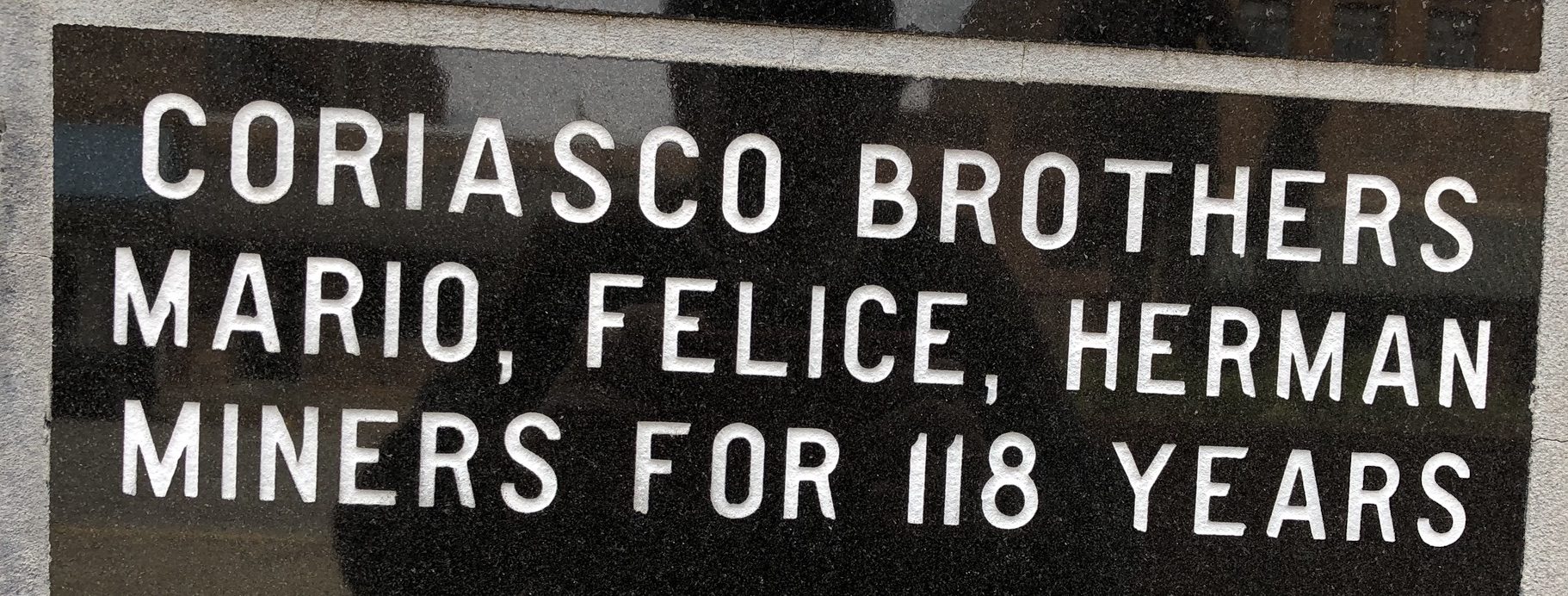

Indeed, many miners or their families (in the case of death) indicate with pride the years worked in the mines. There are many plaques for which generations of family miners are indicated. In this case – three brothers are of Italian origin or ancestry. Reading surnames is like an immigration census.

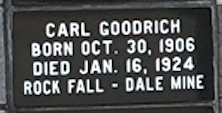

Some plaques refer to specific deaths in mining accidents or commemorate all lives lost.

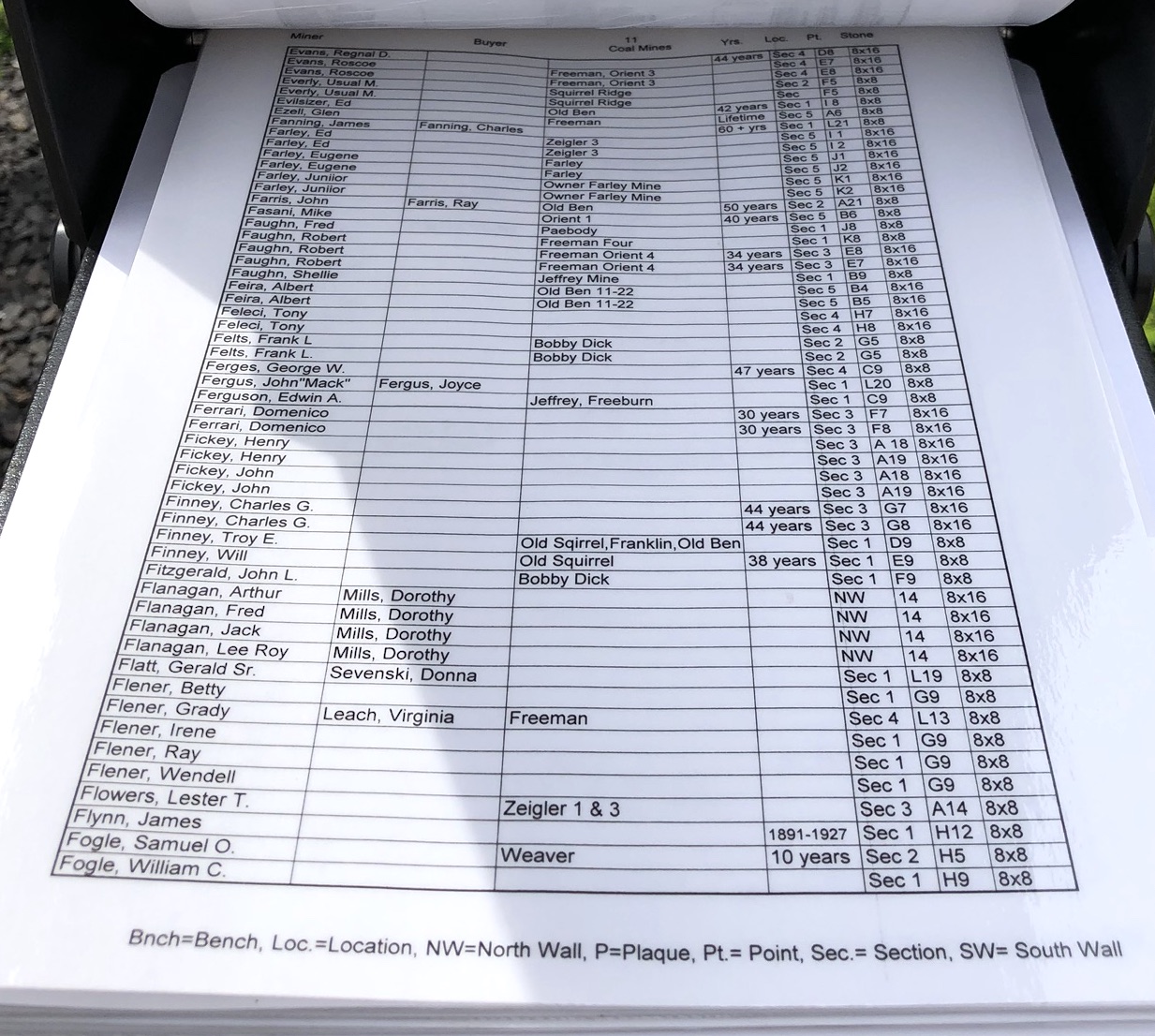

So important are the wall plaques to its patrons and the town that there is directory indicating the location of each plaque by donor/subject and, when known, the relevant mine. The directory is contained in what looks like a mailbox with a pull-down door. This memorial praising the heroism, identity and fortitude of miners in Herrin contrasts greatly with Herrin’s other memorial, below.

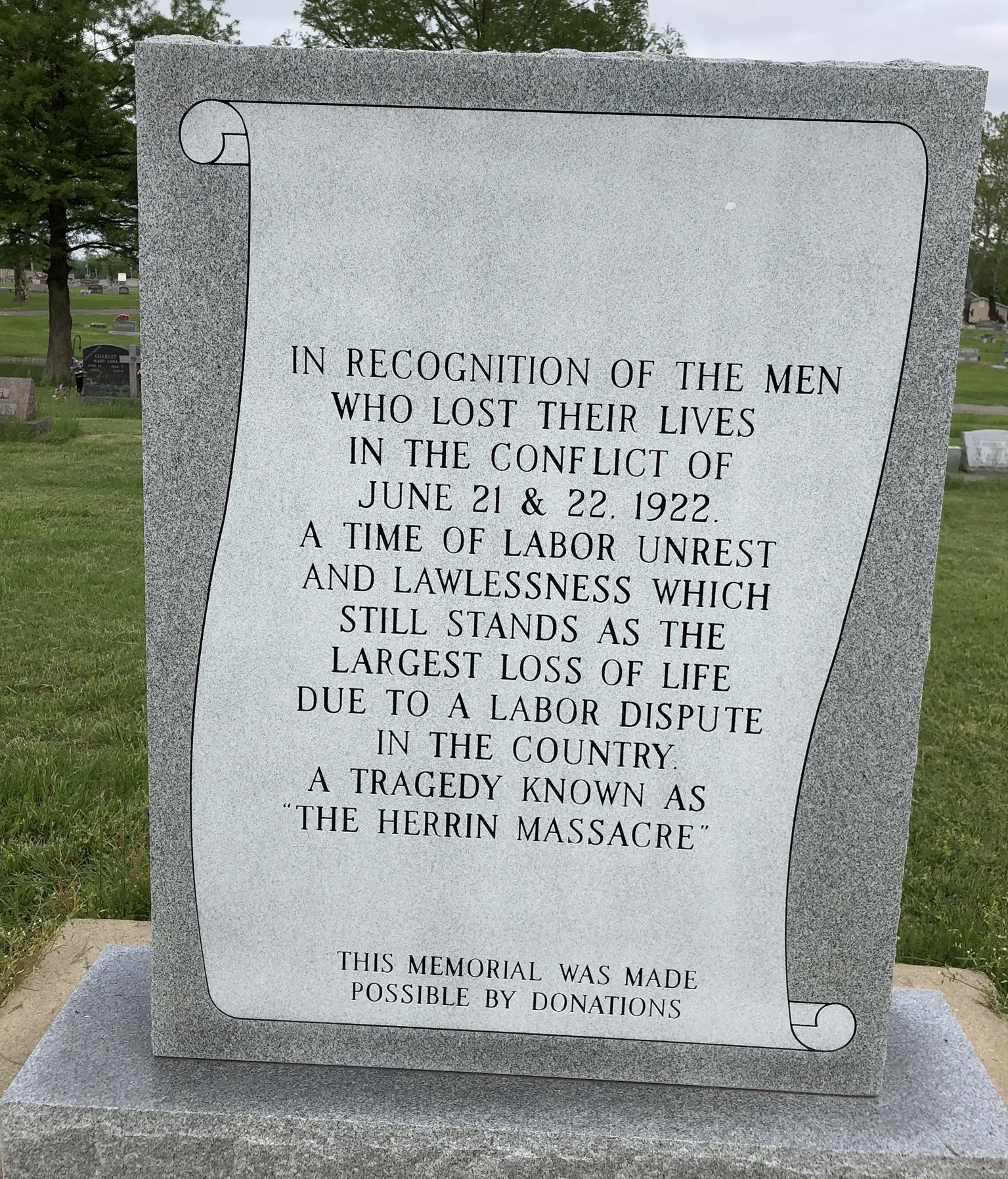

HERRIN MASSACRE MEMORIAL (Herrin City Cemetery)

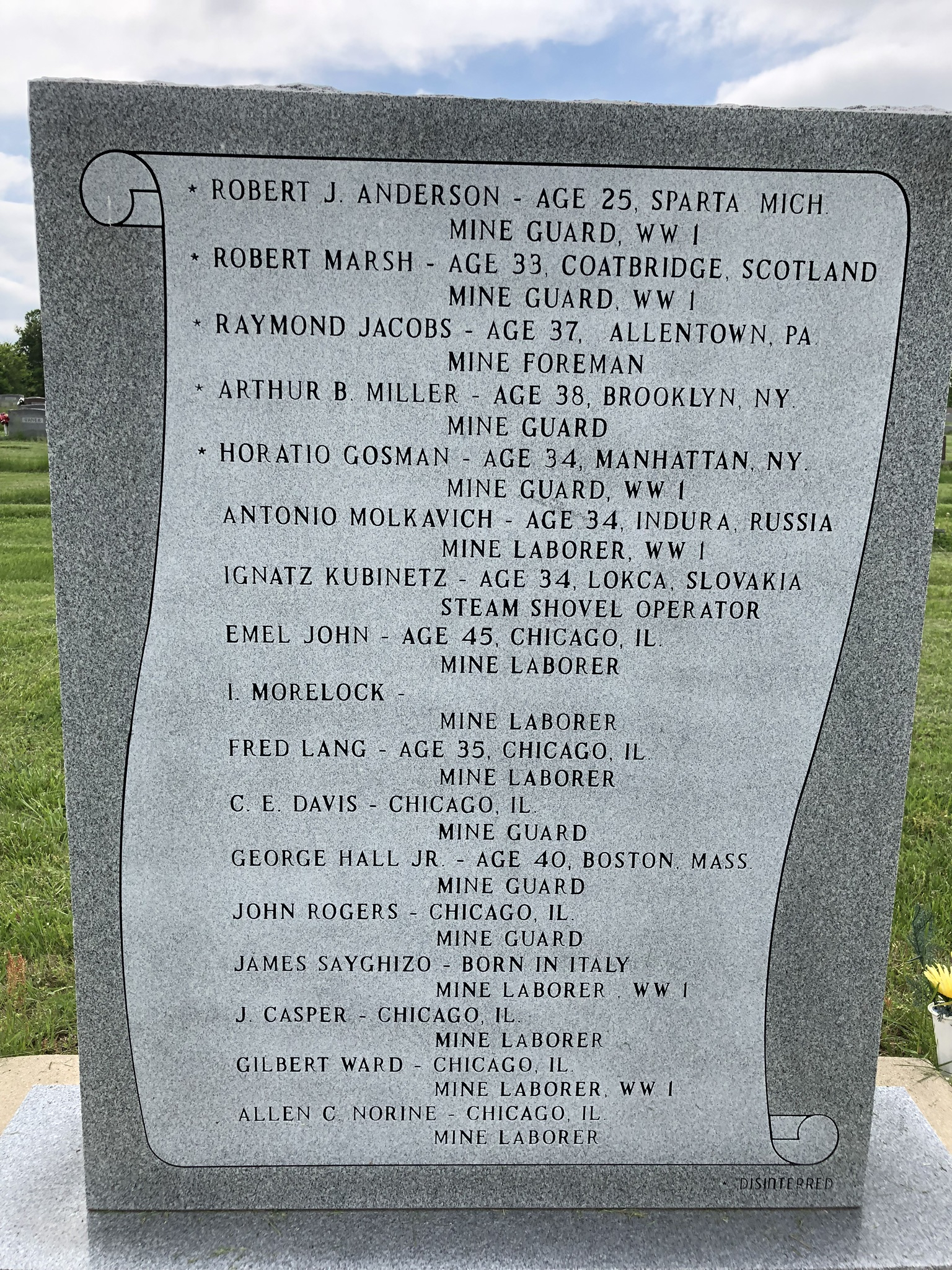

On June 21, 1922 a dispute broke out at the strip mine outside Herrin. The next day United Mine Workers members massacred unarmed miners who had been brought in from Chicago by the company to load coal on the waiting railroad cars. As soon as the unwitting scabs realized the explosive nature of their situation, they ceased working and hoped for safe passage out of the area. But the Herrin miners were intent on executing them. Some were able to escape but at least twenty were killed.

In 2013-2015 a multi-disciplinary research team from Eastern Illinois University and Southern Illinois University in collaboration with several local participants were able to find the unclaimed bodies of the murdered men in unmarked graves in the Herrin City Cemetery. They had been “deliberately lost” as the location became a potters field with poor people buried on top of the massacred dead. Several historical photos of the massacre event as well as photos of the excavation to discover the bodies are available on this website of the Chicago Tribune, which includes informative captions: https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/chi-herrin-massacre-cemetery-photos-20140819-photogallery.html

Herrin’s municipal government has erected a memorial gravestone at the cemetery to recognize these dead of the Herrin Massacre.

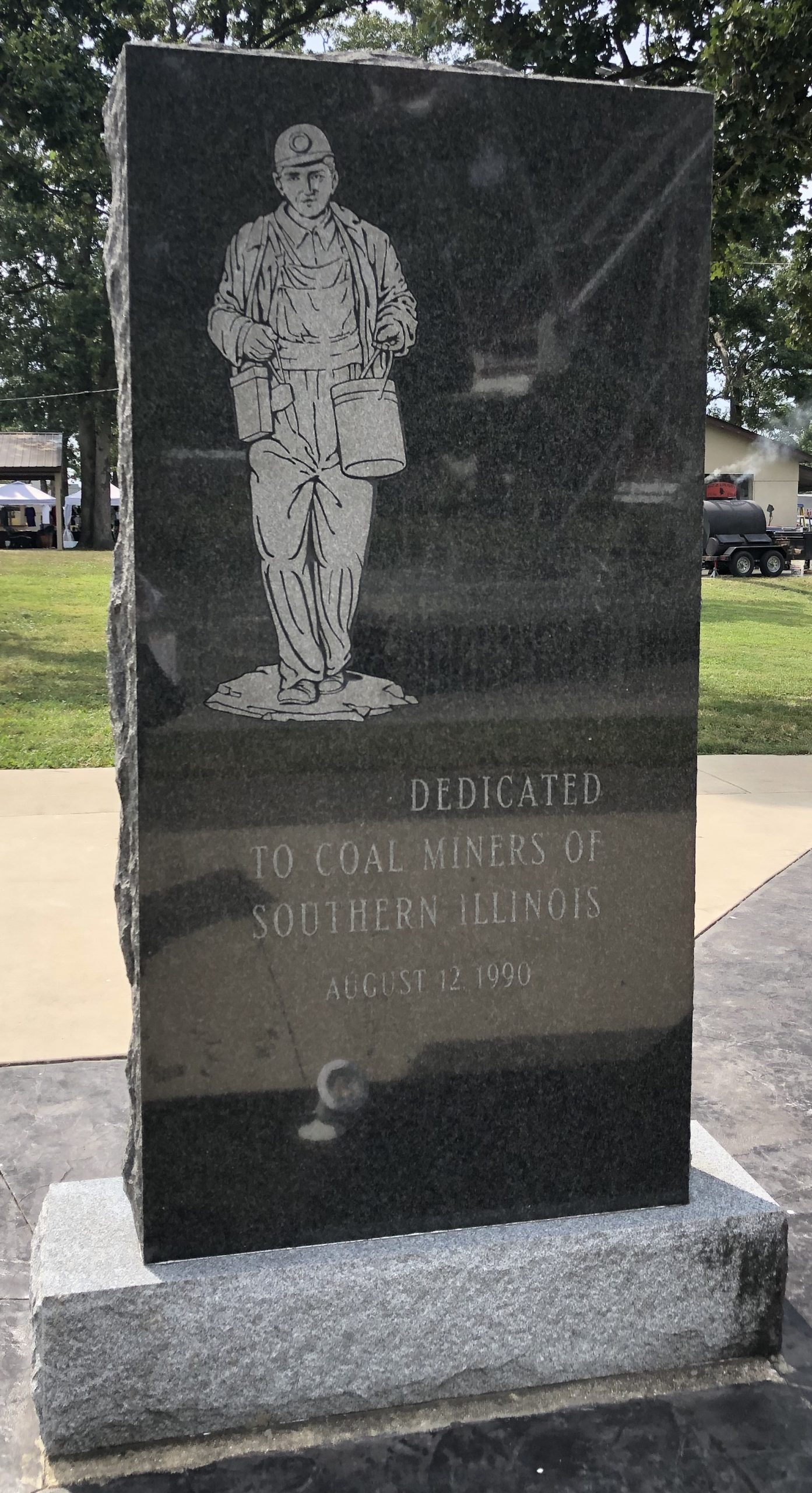

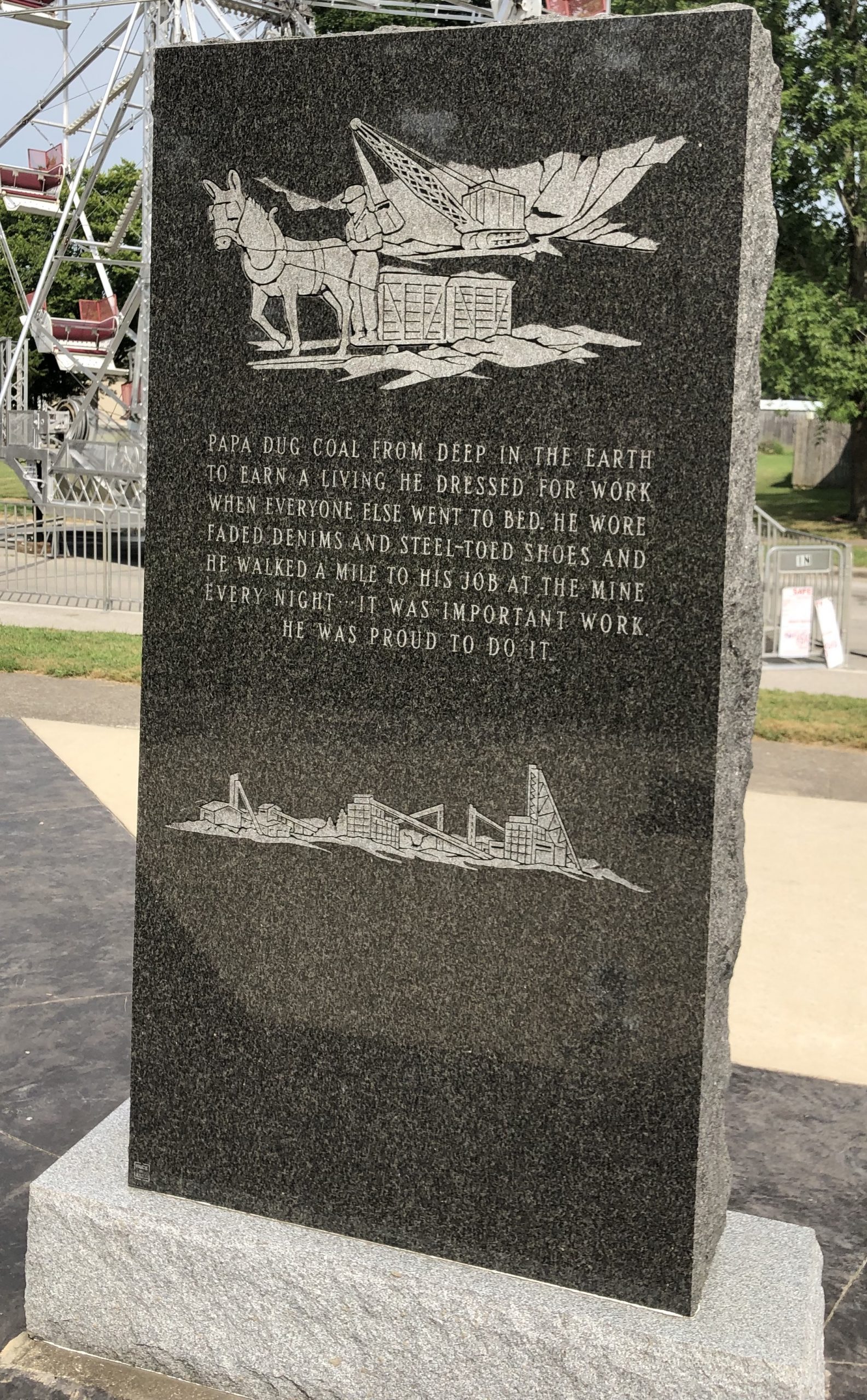

MARISSA (City Park)

This black granite slab bears the image of a coal miner on the front side and an inscription on the back side. The memorial was erected in 1990. Its front says it is “dedicated to coal miners of southern Illinois.” The text on the back says: “Papa dug coal from deep in the earth to earn a living. He dressed for work when everyone else went to bed. He wore faded denims and steel-toed shoes and he walked a mile to his job at the mine every night. It was important work. He was proud to do it.” The May-June 2013 issue of Illinois Heritage states that “a stone slab with a figure of a coal miner was set in Village Park on South Main Street in August 1921.” Information about this earlier monument is needed.

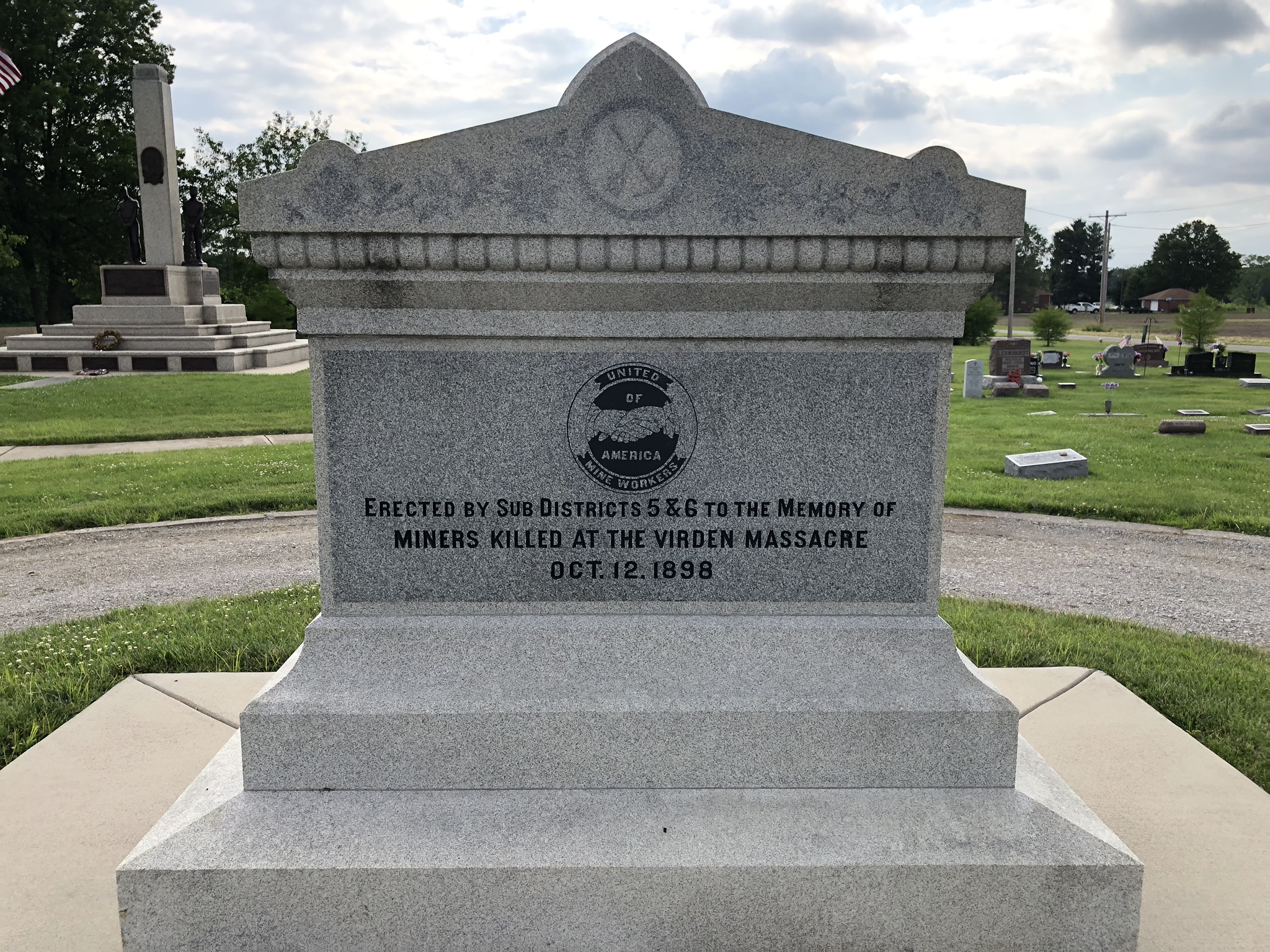

MT OLIVE UNION MINERS CEMETERY

The monumental memorial to Mother Jones in the Union Miners Cemetery in Mt Olive is also a tribute to the martyrs of the Battle of Virden and to the heroes of labor solidarity in the southern Illinois coalfields, such as General Alexander Bradley and the subsequently formed Progressive Miners of America. As well, one can walk among the graves and note the number of them that make reference to union membership. In recognition of the importance of this cemetery, the Mythic Mississippi Project funded the official ISHS marker that stands at the entrance to this hallowed place.

In the image below we see the actual grave site of Mother Jones (foreground), which was incorporated into the Progressive Miners of America Monument in 1936.

A few feet away from the monument is the Virden Massacre memorial marker (below). An interesting article is available at this website: http://genealogytrails.com/ill/macoupin/cem_unionminers.html

Virden Massacre Memorial in the Union Miners Cemetery (Mother Jones Burial and Progressives Monument is seen in left background)

Virden Massacre Memorial in the Union Miners Cemetery (Mother Jones Burial and Progressives Monument is seen in left background)

Tombstone of General Alexander Bradley.

Mt. Olive’s Mother Jones Museum created a magnificent banner honoring the cemetery.

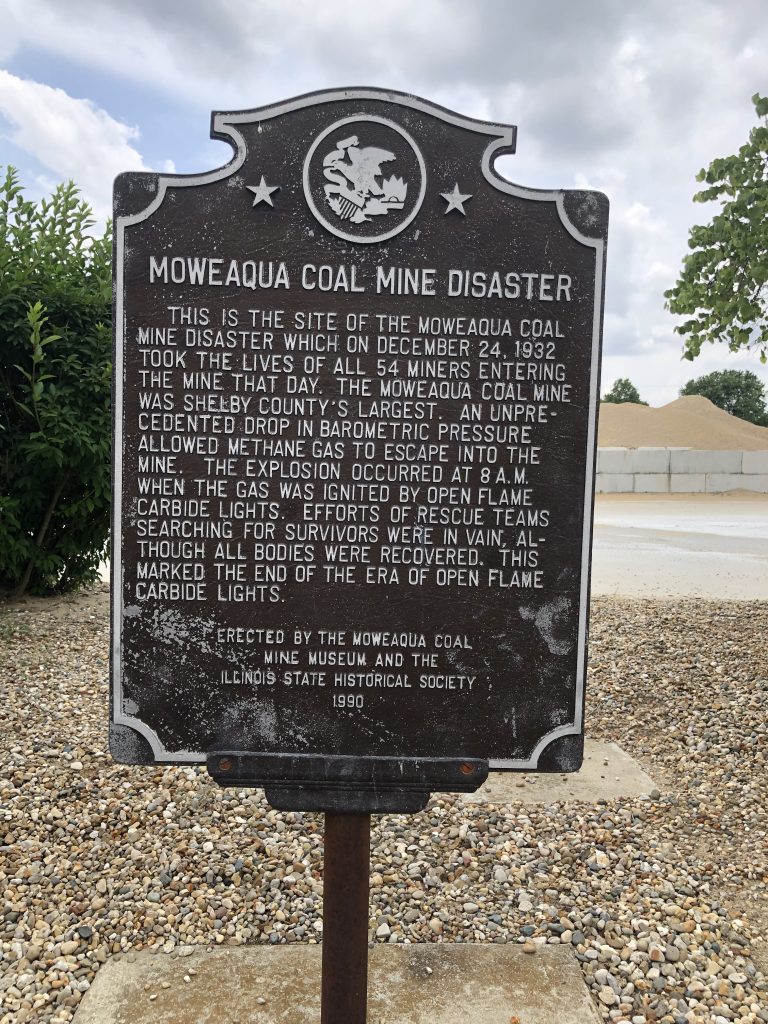

MOWEAQUA

The town of Moweaqua created a memorial on the site of the 1932 coal mine disaster. In addition to its inscribed granite monument in a memorial arrangement, the site is marked by a historical plaque reading:

“This is the site of the Moweaqua Coal Mine Disaster which on December 24, 1932 took the lives of all 54 miners entering the mine that day. The Moweaqua Coal Mine was Shelby County’s largest. An unprecedented drop in barometric pressure allowed methane gas to escape into the mine. The explosion occurred at 8 a.m. when the gas was ignited by open flame carbide lights. Efforts of rescue teams searching for survivors were in vain, although all bodies were recovered. This marked the end of the era of open flame carbide lights.”

PANAMA (Union Cemetery)

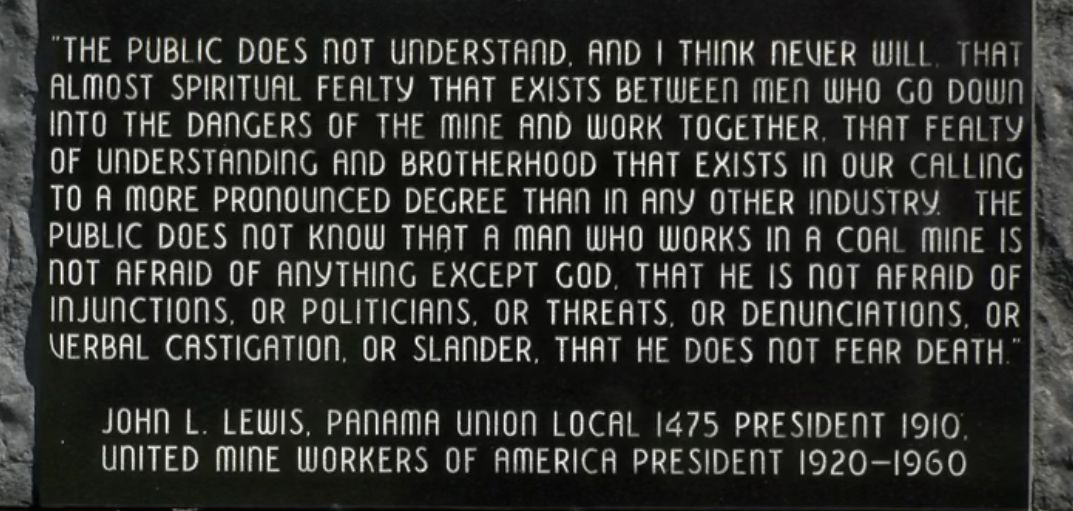

John L. Lewis was President of Local 1475 of the United Mine Workers in Panama where he lived and worked as a coal miner. Only ten years later he had been elected President of the national union. He held that position for forty years with attendant controversy. The ten-foot-tall monument in Panama’s cemetery, however, is not a memorial to Lewis nor is he buried here (he is buried in Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield in a modest plot). The monument was erected in 2003 and it commemorates the terrible April 5, 1915 explosion at the Shoal Creek Coal Co. Panama No. 1 mine in which 11 men died. It is that mine disaster that gives meaning to the words of Lewis inscribed at the base of the memorial. Of significant interest here as with other coal mining memorials is the significant gap in time between a death/labor incident and erection of the monument – each time long after the demise of the local coal industry. Note: we do not know if this is a union cemetery as is the one in Mt. Olive.

SPRINGFIELD (grounds of the State Capitol)

The caption on the pedestal plaque reads: THE COAL MINER”/

TRUE — HE PLAYS NO GRANDSTAND ROLE IN LIFE/BUT HIS IMPORTANCE IS VITAL, GREAT AND JUST:/FOR WITHOUT HIS TOIL IN EARTH CAVERNS DEEP,/ CIVILIZATION WOULD SOON CRUMBLE INTO DUST/ A.D. 1964 FROM HIS POEM- VACHEL DAVIS/ THIS STATUE WAS DEDICATED/ON OCTOBER 16, 1964/ THE SCULPTOR WAS JOHN SZATON OF TINLEY PARK, ILLINOIS

TAYLORVILLE (Oak Hill Cemetery)

The tombstone George Franklin Bilyeu is included here because he was one of the Virden martyrs. His monument in the cemetery is so large and so deliberately scripted as a memorial not just to him but to a cause that it should be interpreted as such. Atop a tall column stands the life-sized image of a miner wearing a miners helmet with light and carrying a pickaxe and shovel in either hand. On the pedestal appears the United Mine Workers logo celebrating the achievement of an 8-hour shift in 1898 (a result of the Virden event) and below are the biographical information (George Franklin Belyeu BORN January 6, 1854 DIED October 12, 1898) and the epitaph: “Lost his life fighting for industrial liberty at Virden, Illinois October 12, 1898. See the images here:

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/116091029/george-franklin-bilyeu#view-photo=87324334

VIRDEN (town square)

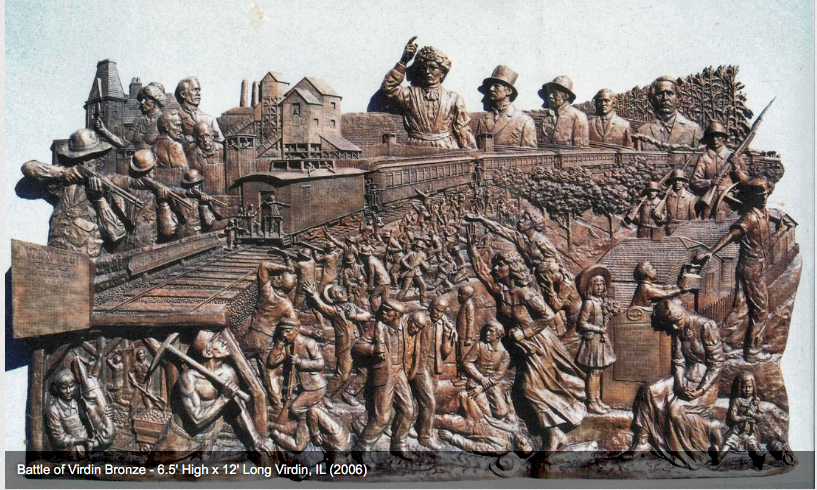

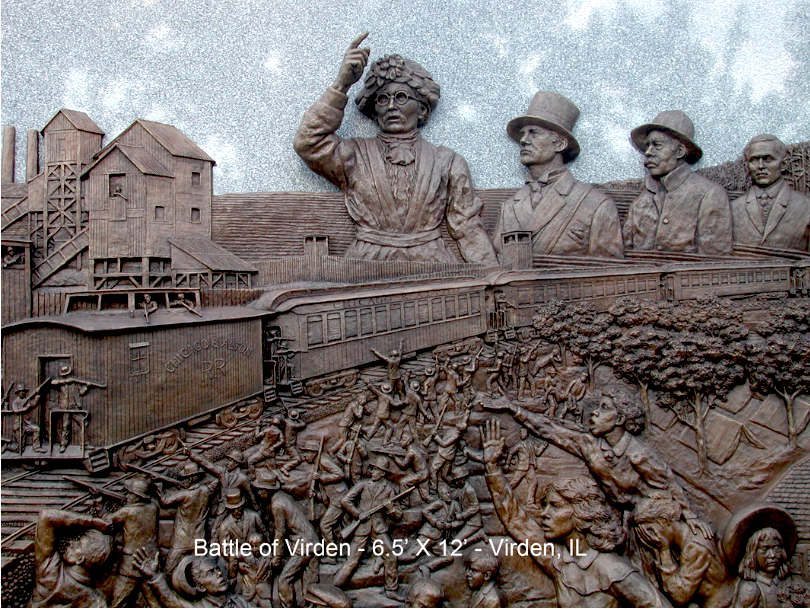

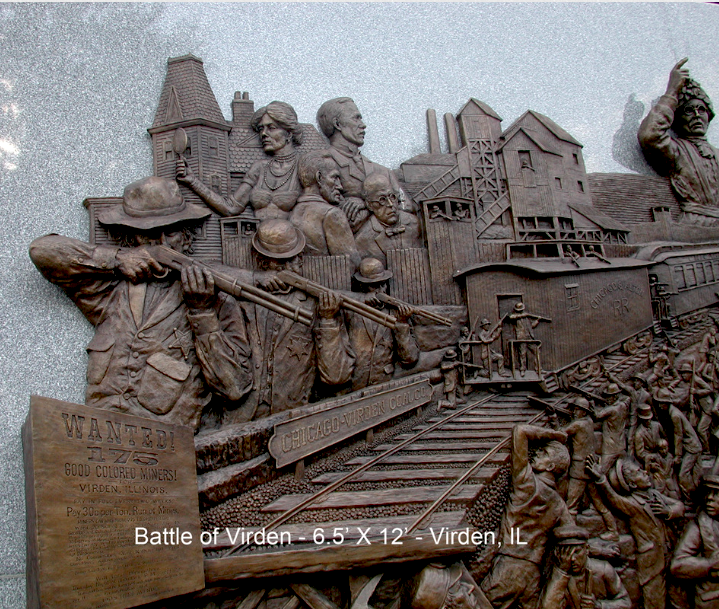

Although Virden did not permit the dead miners in the 1898 labor battle to be buried in the town cemetery, more than one hundred years later a coalition of major patrons (State of Illinois Coal Office, UMWA District 12, Illinois AFL-CIO, City of Virden, principal individual donors) and small donors raised the funds with which to commission a memorial representing the event that took place here. It is a magnificent, evocative bronze bas-relief measuring 6.5’ x 12’ that was created by artist David Seagraves of Elizabeth, IL. It was unveiled in the Virden town square in October 2006.

The detail on this beautiful monument is extraordinary. We show its elements below in images generously provided by Mr. Seagraves.

WEST FRANKFORT (100 E. Main)

Coal Miners Memorial Park honors the 119 miners killed in the Orient Mine No 2 disaster on December 21,1951. Because of the date of the explosion, there are many older residents who remember it and many “baby boomer” adults who grew up hearing about it. The Southern Illinoisan website has published the heartbreaking front page of its first issue after the explosion, before the full scale of the tragedy was known. A memorial service is regularly held to commemorate the event.