Cahokia Mounds is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1982 on the basis of two criteria of outstanding universal value: “it bears a unique [and] exceptional testimony to … a civilization which … has disappeared” (iii) and it is “an outstanding example of a type of building, architectur[e] [and] landscape which illustrates [a] significant stage in human history” (iv). As it does for most of the archaeological sites on the World Heritage List, UNESCO has sponsored this brief video introduction: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3vN4S1jFUp0

See World Heritage designation plaque in upper right.

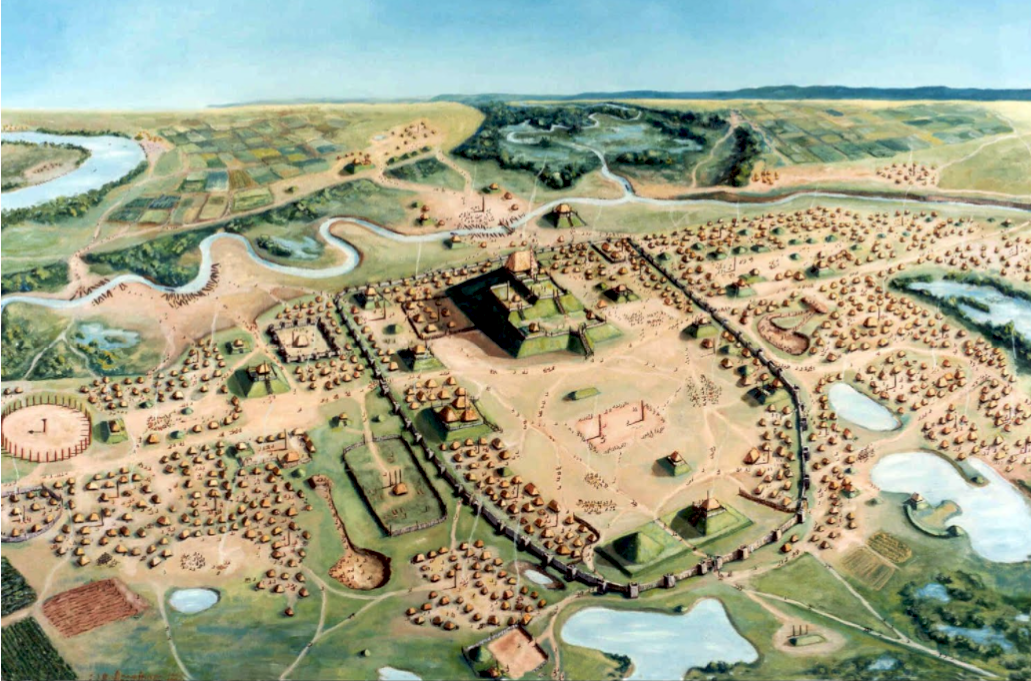

Cahokia Mounds was the largest settlement in prehispanic America north of the Basin of Mexico. It covered 3,200 acres. There were residential neighborhoods, plazas, temples, astronomical observatories and the great Monks Mound.

Cahokia was a bustling city that erupted onto the Middle Mississippi Valley landscape ca. 1050 AD through dramatic social and political events. Cahokia Mounds was a planned site that significantly altered the native cultural patterns that preceded it. Not only did it attract tens of thousands of people to dwell there, it was a pilgrimage center as well with a religion that archaeologists are reconstructing, a religion that spread out from Cahokia across the Midwest, down the Mississippi River and west. With this large geographical area there was exuberant trade in many different kinds of goods. Cahokia’s rapid expansion has been called “a great civilizing social movement” by Timothy Pauketat, a major Cahokia scholar and current director of the Illinois Archaeological Survey. But this “big bang” did not last. Only one hundred years the waning of Cahokia began.

When Cahokia and the Mississipian world collapsed ca. 1200 AD, the great earthen mounds remained on the landscape. Thus, when early Anglo settlers began moving into the lands of the descendant native peoples, they promulgated a “myth of the moundbuilders”, arguing that the “simple” tribes they saw could not possibly have built the mound-marked landscape. Eventually, that fiction was overturned by indisputable evidence that the (then) contemporary Indians were related. The remarkable archaeological survey of Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis published in their Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley (Smithsonian Institution, 1848 — this was the first publication of the Smithsonian!) gives us an idea of what the Europeans first saw, before they erased so much of the Indigenous past from the surface. 48 maps. 207 engravings. Although Ohio’s earthworks dominate the volume, Cahokia is mentioned with the indication of other smaller mounds nearby and across the river at St Louis. The book can be read online though the Gutenberg Project: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/49668/49668-h/49668-h.htm

Today most of Cahokia’s mounds are gone – although Monks Mound still towers. Unlike sites elsewhere such as Machu Picchu, Teotihuacan and Petra, a mind-boggling visual “wow” is missing, notwithstanding what archaeologists have determined was there. Thus, the interpretive center at Cahokia Mounds plays an especially important role.

It is {“type”:”block”,”srcClientIds”:[“4f5ca1bb-6907-4688-803f-55c46a787d5f”],”srcRootClientId”:””}a superb museum with compelling dioramas, artifact exhibitions, maquettes, maps and other illustrations that truly help the visitor appreciate the significance of the site.

And coming in 2023-24 is an Augmented Reality app for the site itself, so that visitors will be able to “see” how the mounds and open spaces (as perceived today) were really used and what they really looked like a thousand years ago.

Watch this interview with Site Superintendent Lori Belknap to understand the challenges and accomplishments involved in managing this great site.

Long time site archaeologist, William Iseminger, offers his insight into the archaeological history of Cahokia in this first interview. (SEE below for his second presentation) And read his article about five decades of public interpretation at Cahokia.

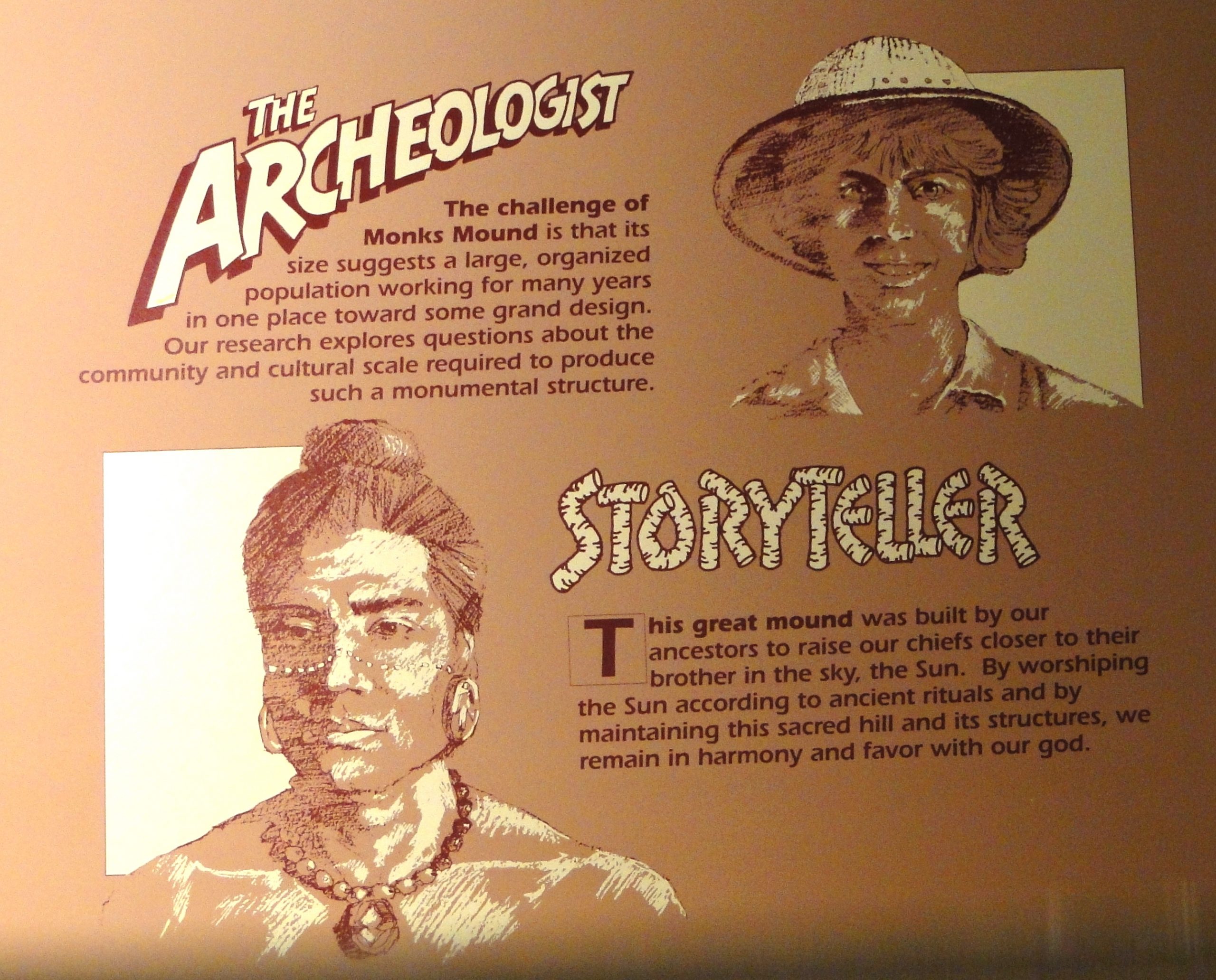

One of the most interesting museological aspects of the interpretive center is its representation of the work of archaeologists and the museum’s contraposition of the professional philosophy of archaeologists in contrast to the cosmology of native peoples, leading to two very different interpretations of Cahokia.

Also interesting is how the museum negotiates the NAGPRA prohibition about the display of Native American human remains. The maquette of Cahokia’s most famous burial appears to finesse the issue.

A major initiative is underway to expand the significance of Cahokia Mounds by having it become a unit of the U.S. National Park Service. This effort is being led by Heartlands Conservancy (see below) in coordination with Illinois political leaders such as Governor JB Pritzker, Senator Dick Durbin, Senator Tammy Duckworth, Congressman Mike Bost, among others, community advocacy associations and Native American tribal groups. If approved, the site would be managed as a partnership between the NPS and the local groups that have enthusiastically pushed for this designation. An important issue to follow is not the obvious improved protection of the site, with expanded boundaries, but also the economic and social development that NPS-inspired tourism could and should bring to Collinsville (where it is located) and the entire adjacent Illinois Metro-East area. Or will Saint Louis remain the primary beneficiary? Listen to two segments of the US/ICOMOS webinar (May 26, 2022) that discussed some of these issues

: presented by Bill Iseminger

presented by Bill Iseminger

https://uofi.box.com/s/4k1k4azdtvvbw806khoydnboe74gp6xa AND:

https://uofi.box.com/s/wjtht67xfwrgzu4kpexshzlvxg5l3xjq

Also watch this interview with political scientist, Dr. Robert Pahre, about National Parks and the Cahokia site: https://mediaspace.illinois.edu/media/t/1_sipqc7nf

Other important Mississippian civilization archaeological sites in Illinois have been excavated by archaeologists over the years. One of the most interesting of those sites is Emerald Mounds near Lebanon:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iwAjxvL6Y4c

Although there is little to see on the surface, it would be very exciting to visit if there were a state-of-the-art interpretive center.

Among the tragedies that befell the Indian peoples of Illinois was their final expulsion in 1830 under President Andrew Jackson. This was the culminating blow in a process of forced attrition that had been happening for many decades. The government’s Indian Removal Act lumped all tribes east of the Mississippi together and sent them across the river, mostly to Oklahoma. Various contemporary Native American tribes are intensely interested in Cahokia Mounds, drawing a historical connection between themselves and the Mississippian people who built the massive site. The Chickasaw, Peoria and Osage among them trace their ancestry to the Mississippian people who created Cahokia and its extraordinary native world. (Read these articles: https://www.stltoday.com/suburban-journals/illinois/osage-people-claim-link-to-sugarloaf-mound/article_92735709-aef6-5c18-b03d-c09aa3be9b48.html AND https://news.stlpublicradio.org/arts/2019-10-01/native-american-tribes-support-national-park-status-for-cahokia-mounds)

Finally, in 2015 the Champaign-Urbana symphony orchestra performed an original piece by composer Brain Baxter entitled “Cahokia”, which chronicles the rise and fall of the ancient prehistoric metropolis in southern Illinois: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WmiXGu8LjfE

KEY REFERENCES

Cahokia Mounds Museum Society. Cahokia. City of the Sun. (1992) – popular

Emerson, Thomas E. Cahokia and the Archaeology of Power. (University of Alabama Press, 1997) – academic

Pauketat, Timothy R. and Thomas E. Emerson. Cahokia. Domination and Ideology in the Mississippian World. (University of Nebraska Press, 1997) – academic

Chappell, Sally A. Kitt. Cahokia. Mirror of the Cosmos. (University of Chicago Press, 2002) – popular

Pauketat, Timothy R. Ancient Cahokia and the Mississippians. (Cambridge University Press, 2004) – academic