Early Alton: Origins and Commerce

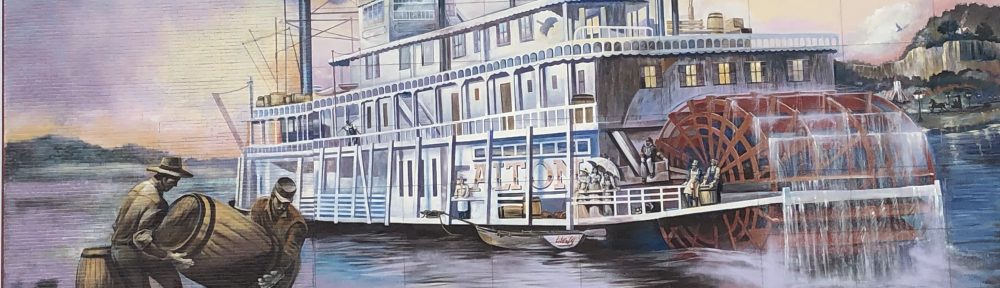

Alton originated as a river town in 1817-18 and, predictably, was a commercial center because of its location on the Mississippi River at the confluence of the Illinois and Missouri Rivers. Moreover, it is effectively at the geographic center of the Mississippi River, between the Minnesota headwaters and the mouth near New Orleans.

It takes little imagination to envision commercial shipping on the river in Alton’s heyday. Indeed, in the 1830s Alton was the largest city in Illinois. In addition to freight, steamboats carried passengers. One easily recalls Mark Twain’s Life on the Mississippi and Edna Ferber’s Showboat.

Alton was overtaken by St. Louis. Nevertheless, Alton prospered as hundreds of steamboats traveled the Mississippi. For decades rivers were faster and more efficient than railroads for bulk cargo (and for soldiers during the Civil War). But in the latter part of the 19thcentury railroads surpassed the steamers. These railroads further supported Alton’s industrialization. Over the later 19thcentury and into the 20thcentury Alton’s commerce included grain storage and transport, brick production, steel manufacturing, glass bottling and cardboard box manufacture. Evidence of some of this vibrant economy can still be seen in the many brick-paved streets of Alton and the gigantic Ardent Mills grain silos along the waterfront, which are the most iconic landmark of the city. (That relationship to the Mississippi River was severely challenged during the June 2019 flood, one of many such dramatic events). Moreover, Alton’s vibrant commercial economy created immense wealth for many inhabitants, as seen in the beautiful Federal, Italianate, Queen Anne and Victorian homes on steep streets that rise up from the river.

Moreover, Alton’s vibrant commercial economy created immense wealth for many inhabitants, as seen in the beautiful Federal, Italianate, Queen Anne and Victorian homes on steep streets that rise up from the river.

In terms of our project’s interest in cultural heritage and its deployment for economic development through tourism, Alton is exceptional. A walk through Alton is a journey through some of America’s most important history.

Abolitionists

Alton’s dramatic history of engagement with the abolitionist movement is its enduring signature. Illinois was a free state across the river from the slave state of Missouri. Although some members of Alton society were pro-slavery, there was a group of dedicated individuals against that institution.

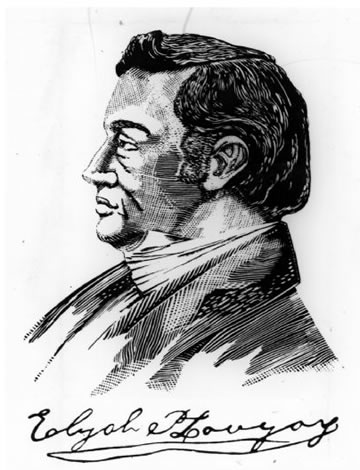

Elijah Lovejoy is one of the most famed abolitionists in the Alton area for his persistent, but ultimately fatal, efforts in the anti-slavery movement. Lovejoy was publishing anti-slavery treatises in St. Louis but was forced across the river in 1836 because of his abolitionist work. He re-settled in Alton to set up his newspaper, the Alton Observer. His printing press was almost immediately thrown into the river by a pro-slavery mob, as were his second and third presses.

Lovejoy persisted. But on the night of November 7, 1837 a pro-slavery mob descended on the warehouse where Lovejoy and his supporters were protecting the fourth press. Lovejoy was fatally shot by one of them and the mob threw the press into the Mississippi. Lovejoy is widely regarded as the first martyr of the abolition movement. He is simultaneously a hero of the concept of a free press.

Lovejoy’s printing press was discovered in and recovered from the Mississippi River in 1915 by personnel from the Sparks Milling Company, now the site of Ardent Mills. It had pride of place in the offices of the Alton Telegraph for eighty years before being donated to the Hayner Public Library in 2018 where it stands today inside the entrance (401 State Street). Please watch this video that includes an actor portraying Elijah Lovejoy:

https://m.riverbender.com/video/details.cfm?id=3439

In 1897 a grand monument to Elijah Lovejoy was erected at the top of a hill (Fifth Street and Monument Avenue – today, the summit of the Alton National Cemetery), with a commanding view of the Mississippi River. It is comprised of a 93-ft tall column surmounted by a 17-ft tall winged Figure of Victory.  Three statements made by Lovejoy were placed as inscriptions at the base of the column and express Lovejoy’s understanding of his action:

Three statements made by Lovejoy were placed as inscriptions at the base of the column and express Lovejoy’s understanding of his action:

freedom of speech:

But, gentlemen, as long as I am an American citizen, and as long as American blood runs in these veins, I shall hold myself at liberty to speak, to write, to publish whatever I please on any subject–being amenable to the laws of my country for the same.

religious justification for his opposition to slavery:

I have sworn eternal opposition to slavery, and by the blessing of God, I will never go back.

steadfastness in the face of perceived lethal danger:

If the laws of my country fail to protect me I appeal to God, and with him I cheerfully rest my cause. I can die at my post but I cannot desert it.

Elijah’s brother, Owen Lovejoy, was also a fierce abolitionist and lived on to fight against the institution of slavery at home and in the halls of Congress. The Owen Lovejoy homestead in Princeton, IL is now a National Historic Landmark, in recognition of the significant activities carried out by the Lovejoy brothers, and the site’s importance as a safe haven.

Watch our interview with Lacy McDonald in which she explains the history and significance of Elijah Lovejoy and moves up in time to consider the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debate at Alton and Alton’s Civil War history:

https://mediaspace.illinois.edu/media/t/1_gweuiofm

See the announcement of a new book about Elijah Lovejoy on our “Sites of Conscience” webpage: https://mythicmississippi.illinois.edu/sites-of-conscience/

See the announcement of a new book about Elijah Lovejoy on our “Sites of Conscience” webpage: https://mythicmississippi.illinois.edu/sites-of-conscience/

Evidence of the Underground Railroad

Some abolitionists created tunnels under their homes that became stops on the Underground Railroad, aiding escaping slaves to get to freedom further north.

The Enos Apartments (325 E. 3rdStreet) were a stop (a safe house) on the Underground Railroad. An additional eight Underground Railroad sites are in the Alton area (see discussion on the Alton section of the African American Heritage page: https://mythicmississippi.illinois.edu/african-american-heritage/ugrr/ugrr-alton/

Ryder Building: when Lincoln was an attorney

Lincoln the lawyer was peripatetic, traveling widely across the state. In Alton he visited clients many times. The Ryder Building (which today houses the wonderful restaurant called My Just Desserts) was the courthouse where Lincoln practiced. We know that he delivered a speech there in support of the Whig Party candidate, William Henry Harrison. And the Ryder Building may have been the site of the Lovejoy murder trial (which did not result in any conviction). 31 East Broadway. The Franklin House –> Lincoln Hotel –> Lincoln Lofts

The Franklin House –> Lincoln Hotel –> Lincoln Lofts

Abraham Lincoln ate and stayed overnight (October 14, 1858) here before his debate with Stephen Douglas the next day. At the time, the Franklin House was one of the largest and finest hotels in Alton. 208 State Street.

The Seventh (Final) Lincoln-Douglas Debate: Lincoln-Douglas Square

A sculptural ensemble stands on this spot where, on October 15, 1858, Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas engaged in the last of their debates before the Illinois election for the U.S. Senate. Spectators to the debate arrived by steamboat and train from all over Illinois as well as from slave-holding Missouri to witness the event. The bronze statues of a declamatory Douglas and pensive Lincoln were unveiled in 1995. They are accompanied by a series of explanatory placards around the square. Distinguished Lincoln historian, Professor Graham Peck at UIS has produced (with Nathan Peck) a unique and provocative film about the debates in their era, called “Lincoln and Douglas: Touring Illinois in Turbulent Times” (2021). It is embedded his website and is highly recommended: https://www.civilwarprof.com/films

A sculptural ensemble stands on this spot where, on October 15, 1858, Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas engaged in the last of their debates before the Illinois election for the U.S. Senate. Spectators to the debate arrived by steamboat and train from all over Illinois as well as from slave-holding Missouri to witness the event. The bronze statues of a declamatory Douglas and pensive Lincoln were unveiled in 1995. They are accompanied by a series of explanatory placards around the square. Distinguished Lincoln historian, Professor Graham Peck at UIS has produced (with Nathan Peck) a unique and provocative film about the debates in their era, called “Lincoln and Douglas: Touring Illinois in Turbulent Times” (2021). It is embedded his website and is highly recommended: https://www.civilwarprof.com/films

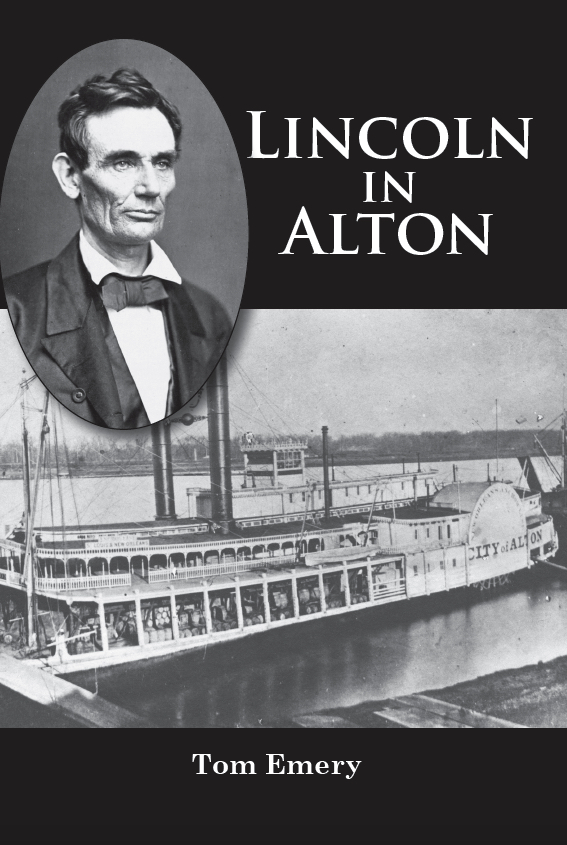

A fascinating new book about Lincoln in Alton has just been published by author Tom Emery (2021).

History in Print, 337 E. Second South, Carlinville, IL 62626

History in Print, 337 E. Second South, Carlinville, IL 62626

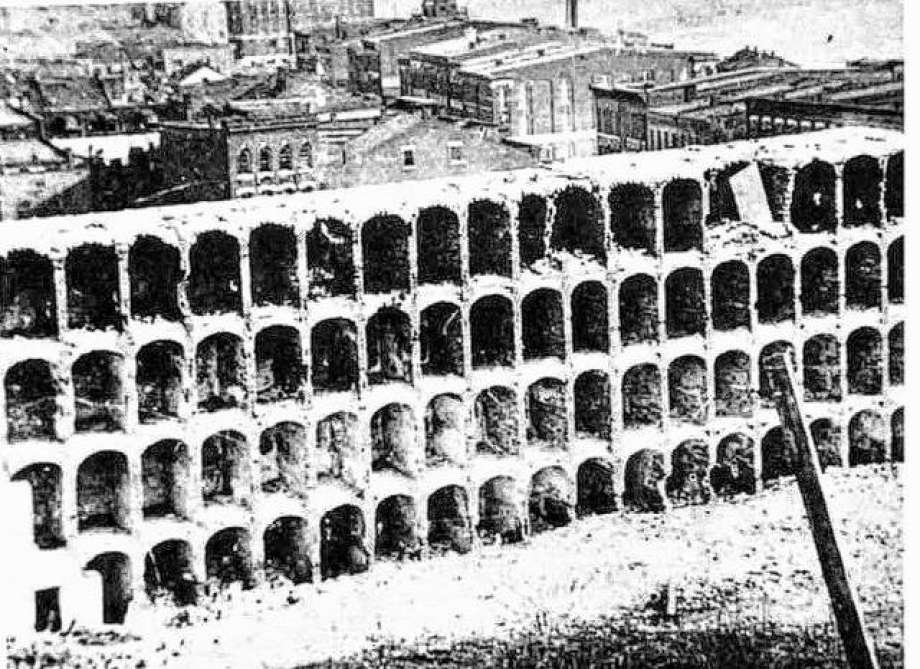

Remaining physical evidence of the Civil War

1) Corner wall of the military prison. This is the only wall section that remains of the first penitentiary built in Illinois, 1833. Located on the 200 block of William Street, by 1857 there were 256 cells for inmates. Conditions even at that time were considered so deplorable that prisoners were moved to Joliet. But in 1862, during the Civil War, the jail re-opened to hold Confederate soldiers and thus it became a military prison. The corner portion (RIGHT)  of an original cell block (BELOW) is on the National Register of Historic Places.

of an original cell block (BELOW) is on the National Register of Historic Places.

(1870 photo in The Alton Telegraph)

Watch this little video produced by Great Rivers & Routes (on Facebook) about the Confederate Prison: https://www.facebook.com/274980350323/videos/10153730416545324/?__so__=channel_tab&__rv__=all_videos_card

2) Alton National Cemetery. The cemetery was started to accommodate the Union dead. It is one of 14 Civil War military burial grounds that were authorized in 1862 as the death toll mounted. At the end of the civil war there were 151 marked graves here, and 12 for the unknown. As is ubiquitous at all military cemeteries, this one is characterized by row upon row of evenly ordered, identically sized markers. The cemetery was inscribed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2011. It is located at 600 Pearl Steet.

3) North Alton Confederate Cemetery. A Confederate mass grave was created on the north side of Alton. It holds the dead soldiers from the military prison. Conditions were deplorable, worsened by a smallpox epidemic. 1,354 Confederate soldiers died (some sources say 1,364 dead). Although the dead rest unmarked below the rolling lawn, a 57-ft tall stone obelisk, completed in 1909, has bronze plaques on all four sides on which the names and units of the deceased are recorded. It is located in a quiet neighborhood on Rozier Street.

The Lyman Trumbull House

Lyman Trumbull was an Illinois Secretary of State and an Illinois Supreme Court Justice. But it is his service as a U.S. Senator, beginning in 1855, and his close association with Abraham Lincoln and support for the Union cause that adumbrate his heroic achievement. As Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Trumbull was the co-author of 13thAmendment of the United States Constitution, which permanently abolished slavery. He further co-authored the 14thand 15th Amendments (citizenry and voting rights, applied to African Americans) and the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

(photo: ScottinAlton, wikimedia commons)

(photo: ScottinAlton, wikimedia commons)

Trumbull’s home is a National Historic Landmark, which is the most prestigious designation a building can receive in the United States. While the house is lovely, it is the exceptional achievement of its owner that justified the honor.

1105 Henry Street.

Scott Bibb Historic Marker (located at the Scott Bibb Center of Lewis & Clark Community College. 1004 E. 5th St.)

A historic marker unveiled on June 19, 2017 reads:

“SCOTT BIBB (1855-1909). Scott Bibb was the plaintiff in the Alton School Case, a series of lawsuits that sought to retain Alton’s desegregated schools, which had existed in Alton from 1872 to 1897, a short-lived outcome of the Reconstruction Era. When Alton city officials re-established segregated schools in the fall of 1897, the African–American community resisted en masse. Bibb brought suit in The People of the State of Illinois, ex-rel. Scott Bibb vs. The Mayor and Common Council of the City of Alton. Over the next 11 years the lawsuit was appealed to the Illinois Supreme Court 5 times. In 1908 the Illinois Supreme Court ruled in favor of Bibb, but Alton failed to implement the orders of the court, denying African-American students access to white schools. It would take another 50 years before the education system in that city would be desegregated again.” The Mythic Mississippi Project considers the Scott Bibb case further in the lesson plan developed for high school students that deals with critically reading historical texts (see – https://mythicmississippi.illinois.edu/lesson-plans/historical-documents-as-rhetorical-texts/ ) SEE ALSO: “History on Trial: The Alton School Cases”, a fascinating dramatic play that enacts the trials and appeals from 1897-1908. The play was performed at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum on April 21, 2015. It can be watched on-line: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=57_Nlg2tI_c

The Wedge Building and the Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

The United States has a tragic history of political assassination. 1968 was a particularly grim year with the murders of Senator Robert F. Kennedy, brother of the assassinated president, John F. Kennedy (in 1963), and of the great civil rights leader, Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr.

Alton has a connection to the assassination of Dr. King. The official government investigation of the MLK assassination concluded that some money from the heist at the Alton Banking and Trust Co. on July 13, 1967 was used by its perpetrator James Earl Ray to finance his travel across country to murder Dr. King on April 4, 1968. An unofficial website furthermore states that some of the bank money was specifically used to purchase the fatal 30.06 Remington Gamemaster hunting rifle that killed King.  The bank is popularly known as “The Wedge” because of the shape of building. It is long abandoned. There has been a discussion among civic leaders in Alton to rehab it and transform it into a multi-purpose cultural center for Alton residents. On architectural grounds, we very much hope this building can be saved. And as a cultural center it could have a cafe, permanent and temporary exhibition space, a performance stage, and an area for educational activities. This kind of careful scripting would mitigate the possibility of turning The Wedge into a “dark tourism” venue and, instead, further goals of racial reconciliation and social equity in Alton.

The bank is popularly known as “The Wedge” because of the shape of building. It is long abandoned. There has been a discussion among civic leaders in Alton to rehab it and transform it into a multi-purpose cultural center for Alton residents. On architectural grounds, we very much hope this building can be saved. And as a cultural center it could have a cafe, permanent and temporary exhibition space, a performance stage, and an area for educational activities. This kind of careful scripting would mitigate the possibility of turning The Wedge into a “dark tourism” venue and, instead, further goals of racial reconciliation and social equity in Alton.

The National Register of Historic Places

Alton has 3 NRHP districts with a fourth one is under consideration. This is remarkable in a small city of only 28,000 inhabitants.

Hayner Public Library (https://www.haynerlibrary.org/)

The library has an excellent local history and genealogy reference room as well as a series of expertly curated museum display cases containing historic artifacts, documents and photographs about Alton’s history.

An extraordinary resource for all things Alton is the multi-segment podcast of Stephanie Young (Principia College, Elsah), cleverly called All Town, USA. Please listen to the episodes at this link, including the “Special Edition” dealing with the racial disparity evident in the January 6, 2021 insurrection. This will be followed by Episode 8 about African American heritage in Alton. https://alltownusa.org

We are pleased to work in Alton through our collaboration with Alton Works, Great Rivers & Routes DMO, Alton Main Street and the Hayner Public Library.