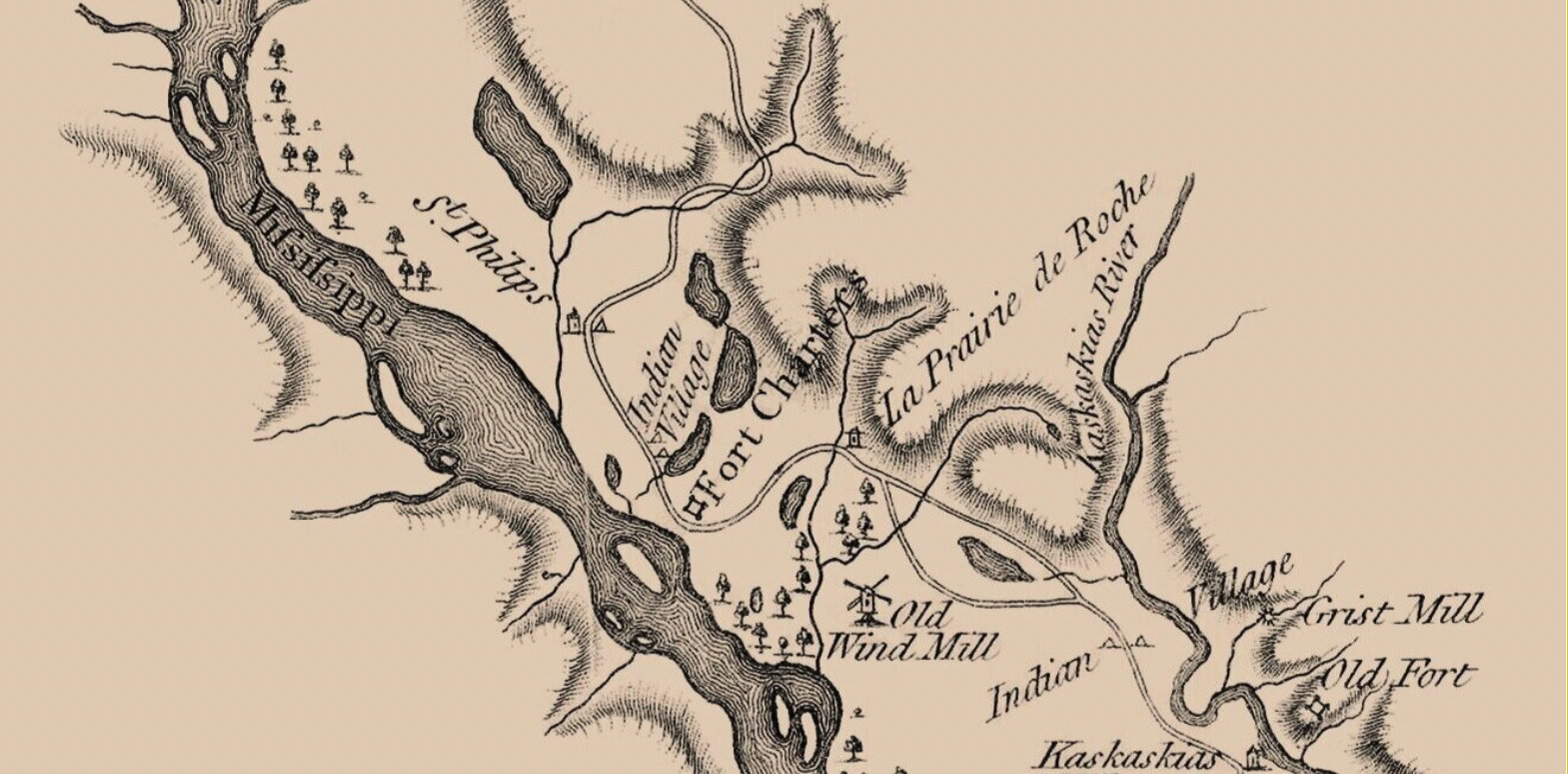

Prairie du Rocher was settled in 1722. Its farming population was protected by nearby Fort de Chartres. Unlike Kaskaskia, the fur trade was not important here. Half of the population was composed of African or Indian slaves, which contrasts significantly with the far fewer number of slaves in the other French towns. The explanation given is that farm labor was needed.

Prairie du Rocher was settled in 1722. Its farming population was protected by nearby Fort de Chartres. Unlike Kaskaskia, the fur trade was not important here. Half of the population was composed of African or Indian slaves, which contrasts significantly with the far fewer number of slaves in the other French towns. The explanation given is that farm labor was needed.

The town has remained continuously occupied, but little of the original French colonial built environment of Prairie du Rocher remains, the most notable example being the Creole House (below), which is on the National Register of Historic Places (1973). The house is appropriately called “creole” because of its French and American elements. Built ca. 1800 it exhibits both the Medieval (and thus French) style of half-timber as well as the American practice of studs set into the ground (poteaux-sur-sol).

Above the town is St Joseph’s Catholic Cemetery, which is fascinating for the number of French surnames on its gravestones – and descendants of many of those families still live in Prairie du Rocher. Of particular importance is the memorial tombstone (below) whose inscription explicitly commemorates the Michigamea Indians, early French adventurers, Black slaves, victims of wars and massacres and others who were buried here.

Prairie du Rocher has revived its French heritage in a performances that animates the town’s current apparent zeal for the historic past. The Rendezvous was invented in 1970 as the U.S. bicentennial approached. It is celebrated at nearby Fort de Chartres and features “frontier life” with pretend soldiers on dress parade in colorful uniforms, traditional craft demonstrations, period music and dancing, black powder shooting events and cannon firings. Visitors can buy hand-made crafts, learn about French kitchen gardens, and watch swordsmen duel, and do food tastings. The annual event is presented by Les Coureurs des Bois de Fort de Chartres and sponsored by Les Amis du Fort de Chartres.

Also as the United States was turning 200 years old in 1776, Prairie du Rocher residents took pride in celebrating the 250th (!) anniversary of their town in 1972. It was on this anniversary that the memorial tombstone and cross (illustrated above) were placed in St Joseph’s Cemetery. In 1976 the town raised money to build a new town hall in the French traditional style.

The other performance of French heritage, however, is authentic in the sense of being a tradition: La Guiannée. It appears to have been celebrated in Prairie du Rocher since its founding. On New Year’s Eve townfolk (originally just men) dress up in old-style clothes, sing French holiday carols and dance – going from house to house, sometimes being invited in. A full explanation is provided by Margaret Kimball Brown in her book, History As They Live It. A Social History of Prairie du Rocher, Illinois (Southern Illinois University Press, 2005) – pp. 275-278.

Other embodied French traditions have disappeared. But La Guiannée is the ritual glue, so to speak, of community identity. Its longevity, particularly in the absence of a tourism prompt, speaks to its importance. And where the visitor to Prairie du Rocher sees a dearth of supporting physical stimuli for a French identity – unlike Ste Genevieve across the river – in Prairie du Rocher it is the families, the family names, the street names and the familiar home styles (though not “screaming” “post-on sill” or Menard-like colonial) and the Catholic Church that together enable a cohesive town identity as well as an identification with the French past – including in the absence of the language. But Prairie du Rocher is not a French town. It is a small, rural American town. Now in the years ending the second decade of the 2000’s, Prairie du Rocher sees a tourism (i.e., economic development) value in its French past.

The Prairie du Rocher Chamber of Commerce has excellent webpages on the history of the town: http://www.visitprairiedurocher.com/historical-information/