Originally called Commerce – a name indicating the town’s aspirations – following the financial panic of 1837 the town of Commerce was greatly diminished. Land was cheap, therefore, in 1839 when Joseph Smith decided it was time to leave Quincy after the many months of shelter the Mormons had received from that generous community. Smith chose Commerce as the new home of the Saints. He renamed Commerce as Nauvoo, which in Hebrew means “beautiful place.” Smith and the Mormon leaders platted the town with blocks within which were homes, each one having a garden and space for necessary domesticated animals. Soon it was one of the fastest growing towns in the U.S. It was briefly the largest city in Illinois. In 1840 Nauvoo was legally registered. By 1844 Nauvoo had more than 12,000 residents, some of whom were converts from England. Nauvoo had a larger population than Chicago at the time and it was the largest city in Illinois.

Notwithstanding the prosperity inside Nauvoo, all was not well outside. Once again relations between the Mormons and their non-Mormon neighbors grew strained, to the point of violence. The city charter was drafted by Smith in such a way as to not separate church and state and not make Nauvoo subject to Illinois civil law. Basically, a non-Mormon could not arrest a Mormon for an offense. And the charter enabled Nauvoo to have a militia. Smith, as mayor, had control of what elsewhere were separate branches of government and society.

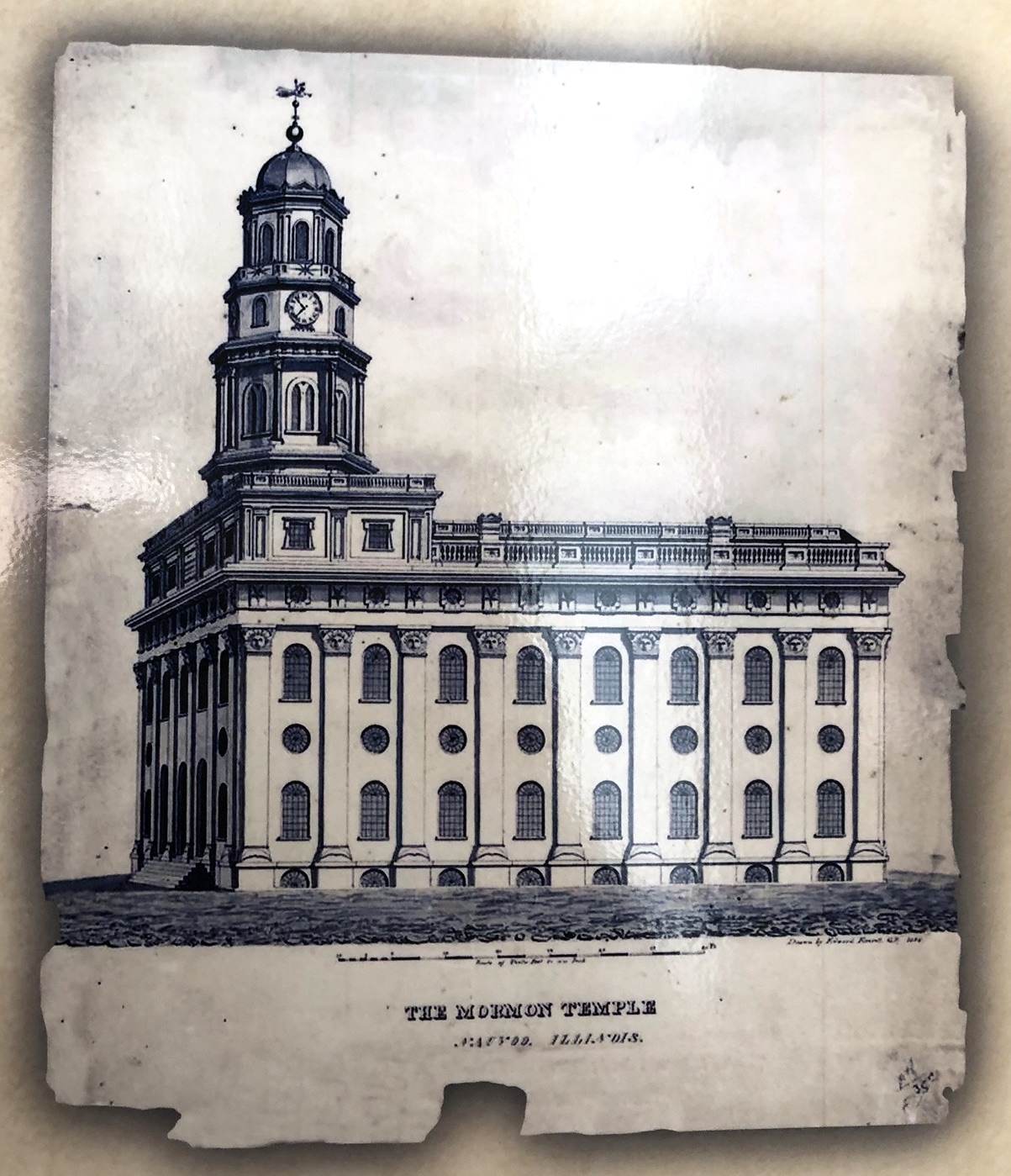

With Nauvoo established, in 1841 Joseph Smith undertook construction of a temple with the physical labor of all able-bodied men in the Mormon community. The Mormon temple was, in its time, the largest structure north of St. Louis and west of Cincinnati. Anyone traveling on the Mississippi River could not have missed seeing the temple, which stood on an elevation in Nauvoo.

In 1844 Charles Lambert, a talented stone cutter from England and convert to Mormonism, designed and carved thirty decorative pilasters for the temple, each with a stone sun face on the capitals to convey a celestial kingdom. Only three sun stones survive.

But the Mormons were being attacked by a newspaper outside Nauvoo, the Warsaw Signal.

In Nauvoo itself a group of dissenting Mormons set up a newspaper, the Nauvoo Expositor, and published a scathing criticism of Smith’s many abuses, inconsistencies and hypocrisies. The Nauvoo police and two hundred other armed men also loyal to Joseph Smith, acting on his orders, smashed and burned the printing press. Smith’s abrogation of freedom of the press (think of Elijah Lovejoy only a few years earlier in Alton, 1837) was the proximal (and final) reason for Illinois Governor Thomas Ford’s demand that Joseph Smith stand trial in Carthage. The other most significant charge against Joseph Smith was treason.

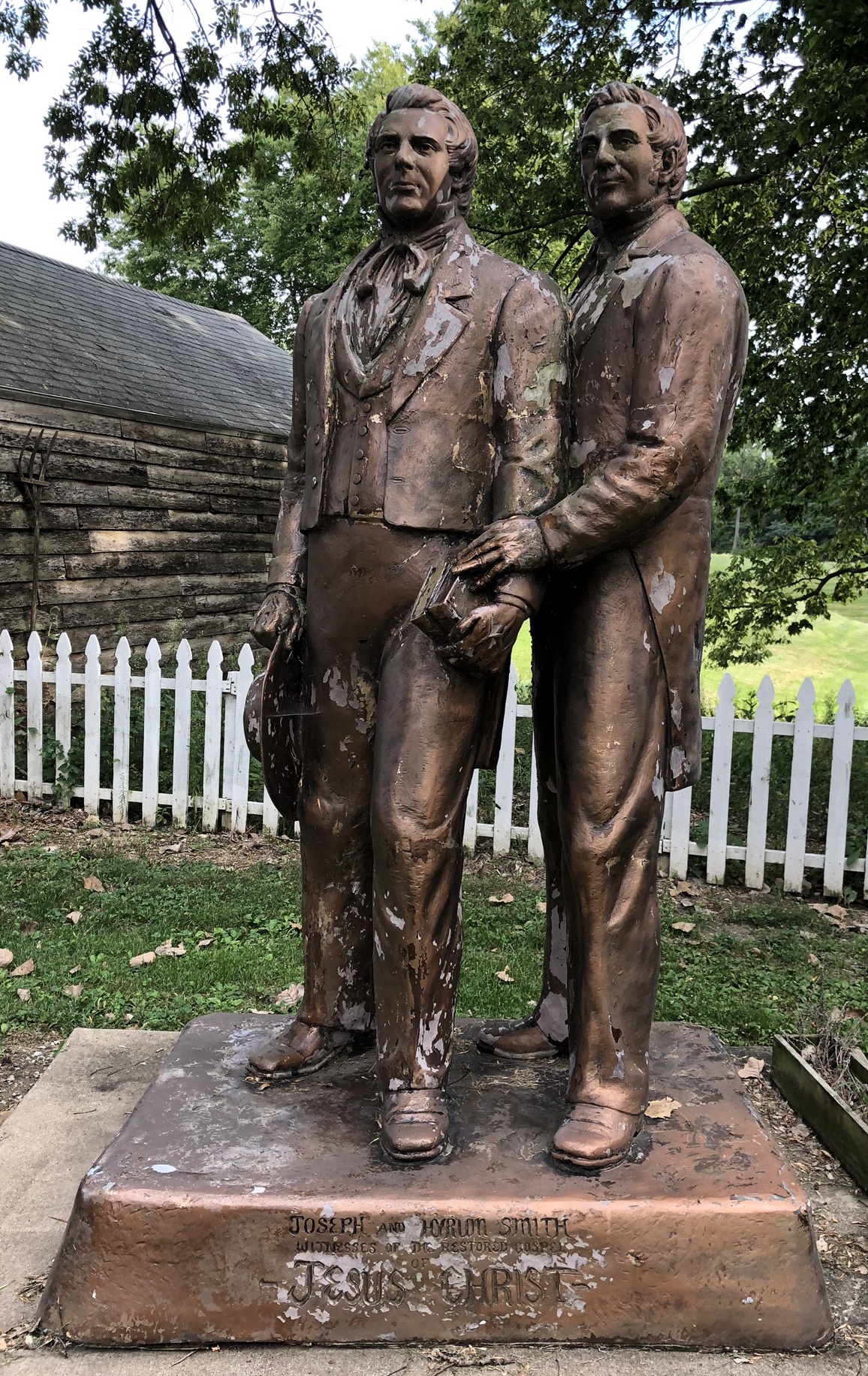

Convinced that that the legal system would again be distorted to support Joseph Smith, a mob from Warsaw amassed outside the Carthage jail on June 27, 1844 and then dozens made their way upstairs to where Joseph Smith, his brother Hyrum and two other Mormon leaders were. In the ensuing gunfight the Smith brothers were killed.

The extrajudicial killing climaxed Mormon fears in Nauvoo of impending destruction of their community. Facing violent hostility from nearby locals because of their growing political power and controversial religious practices, in the winter of 1846 most Mormons in Nauvoo fled back across the Mississippi River – from whence they had escaped Missouri – to undertake a dramatic trek across the western United States, ultimately arriving in Utah and founding Salt Lake City.

After several months in which succession to Joseph Smith’s leadership role was contested, Brigham Young emerged victorious and, still confronting a hostile Illinois neighborhood, decided to lead an exodus of the Mormon inhabitants of Nauvoo to a western territory where the Saints could live as they wished. There may have been as many as 15,000 to 20,000 residents in Nauvoo at the time. In February 1846 the Mormons began crossing the Mississippi River – for the last time. Their great trek west is today recognized by the National Park Service’s Mormon Pioneer Trail, for they were as much American pioneers as the countless other wagon trains so familiar to us from literature and Hollywood movies.

Two years later arsonists burned the temple and a tornado in 1850 completely demolished it. Most Mormons left Nauvoo.

By 1848, just two years after the Mormon exodus, German immigrants (especially) began moving into Nauvoo.

Like the Mormons before them, other people sought their own “paradise on earth” at Nauvoo. The Icarians – a utopian communal society – saw an opportunity to purchase land cheaply in Nauvoo from the fleeing Mormons. In 1849-1850 Icarians migrated up the Mississippi River from their first and failed attempted settlement in Texas along with the French founder of their community, Etienne Cabet. The Icarians hoped to develop a socialist, communal colony along their own ideological lines and without fear of persecution from others. But by 1856 their internal feuding led to the dispersal of that group. When Icaria flourished, there were more than 500 community members in Nauvoo. But by 1856 Icaria started to succumb to internal dissent and various Icarians left to found their own Icarian communities elsewhere.

Nauvoo became a multicultural town – albeit much smaller – composed of Mormons who had not fled, some Icarians (two of whom started a winery still functioning today), and others.

At the start of the twentieth century Mormons from Utah began to think about their place of origin, Nauvoo. The reason for this revival of interest in Nauvoo is uncertain. But in 1905 nearly one hundred congregants of the Latter Day Saints arrived in Nauvoo for a two-day conference. By then the once glorious temple was long a ruin, destroyed first by a fire in 1848 and then a tornado in 1850. It was rubble and the once prosperous town was house foundations and dilapidation. But the assembly had the idea of bringing Nauvoo back to life.

That goal was further advanced when the Mormons became aware of John D. Rockefeller’s investment in Colonial Williamsburg, starting in 1926, and they could watch the reconstruction and rebirth of that town. A Mormon initiative to rebuild Nauvoo, strongly tinged with their religion’s zeal, led to the purchase of the destroyed temple site in 1937 so as to eventually rebuild the temple as well as the town. A major Mormon leader and author, Bryant S. Hinckley, said in 1938 that Nauvoo should rise again so as to “bring into relief one of the most heroic, dramatic and fascinating pioneer achievements ever enacted upon American soil” (quoted in Susan Eastman Black’s beautifully illustrated monograph, The Nauvoo Temple, Millennial Press, 2002). Indeed, too often the role of the Mormons in American frontier history gets lost in the Mormon religion story. Nauvoo is an important part of the history of the United States.

In 1966 excavations began in Nauvoo to recover and restore the original Mormon settlement, leading to the emergence of the academic field of historical archaeology in the United States. Non-Mormon archaeologists realized that Nauvoo needed to be interpreted as a frontier town, just as the Mormon community saw it as a religious center.

In 1961 Nauvoo became one of America’s first National Historic Landmark sites, a major designation from the National Park Service. That designation intersected the Mormon’s Latter Day Saints Church acquisition of property in town and the restoration, over time, of many of the homes of the original settlers. Almost immediately Nauvoo became a tourist attraction.

Today Nauvoo is restored and reconstructed. One sees the town as it is believed to have been when Joseph Smith and the early Mormons lived there. A new temple (consecrated in 2002) replicates the original one. Understandably, Nauvoo is the epicenter of Mormon pilgrimage. Nauvoo’s Mormon community has created its own comprehensive script in a large visitor center.

The town of Nauvoo itself is pleasant with many shops, restaurants and B&B’s attending both Mormon and non-Mormon visitors. Its contemporary dual occupation is truly fascinating.

REFERENCES

Cuerden, Glenn. Image of America. Nauvoo. (Arcadia, 2006) – popular

Esplin, Scott C. Return to the City of Joseph. Modern Mormonism’s Contest for the Soul of Nauvoo. (University of Illinois Press, 2018) – academic

Park, Benjamin E. Kingdom of Nauvoo. The Rise and Fall of a Religion’s Empire on the American Frontier. (Liveright, 2020) – popular

Pykles, Bejamin C. Excavating Nauvoo. The Mormons and the Rise of Historical Archaeology in America. (University of Nebraska Press, 2010) – academic