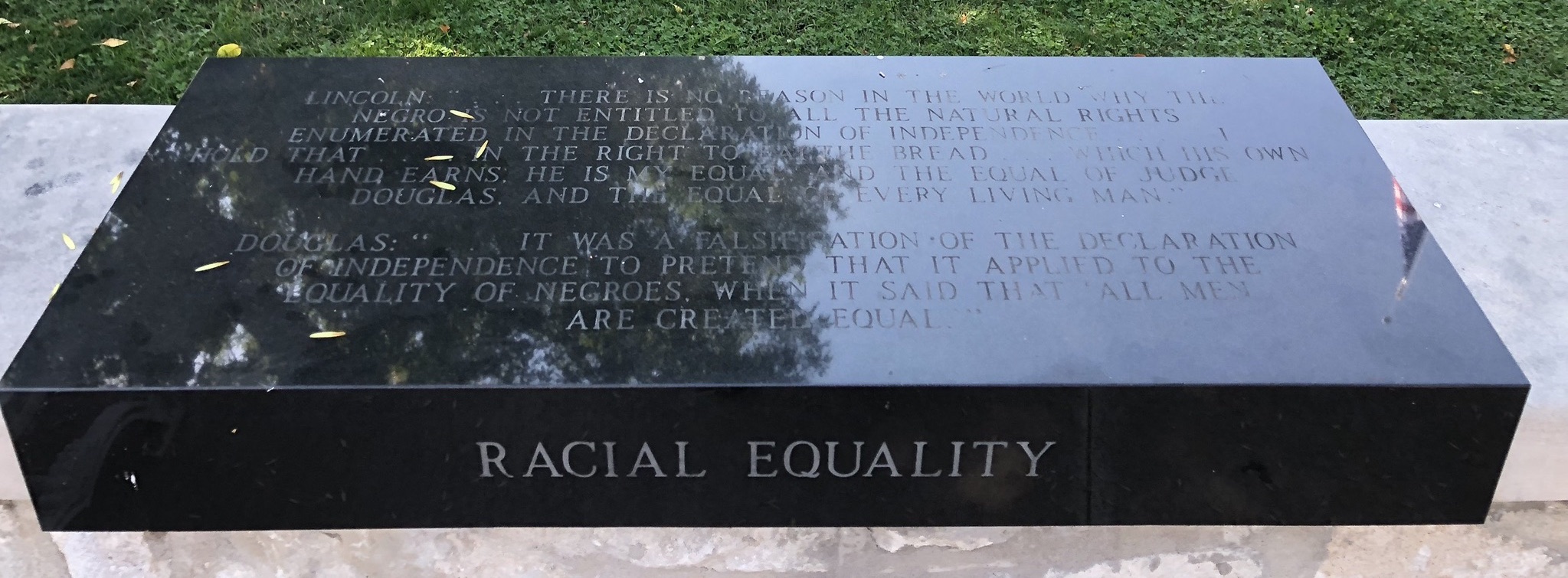

Quincy sits on a dramatic bluff overlooking the Mississippi River. It is one of the most historically important cities of Illinois. It is significant for the charity it showed the Mormons in the winter of 1838-39 (“Quincy-City of Mormon Refuge“). It is significant as the location of the sixth Lincoln-Douglas debate. It is significant as a city with a very strong connection to the German immigration story of Illinois (indeed, one of the historic districts is the German Historic District). And it is significant because it has 3,600 buildings on the National Register of Historic Places with four National Historic Districts and three local historic districts.

Having dealt with Quincy’s Mormon story elsewhere on this website, here we introduce the other three themes – and we note that these do not exhaust Quincy’s interest.

Quincy: African American Heritage

Reference to the sixth Lincoln-Douglas debate in Quincy necessarily invokes our project’s “African American Heritage” theme because this debate, held in the town square (Washington Park) on the afternoon of October 13, 1858, was almost entirely devoted to the issue of slavery. An extraordinary enactment of the almost three-hour debate was performed for C-SPAN on October 9, 1994. The video is available here: https://www.c-span.org/video/?59825-1/lincoln-douglas-quincy-debate

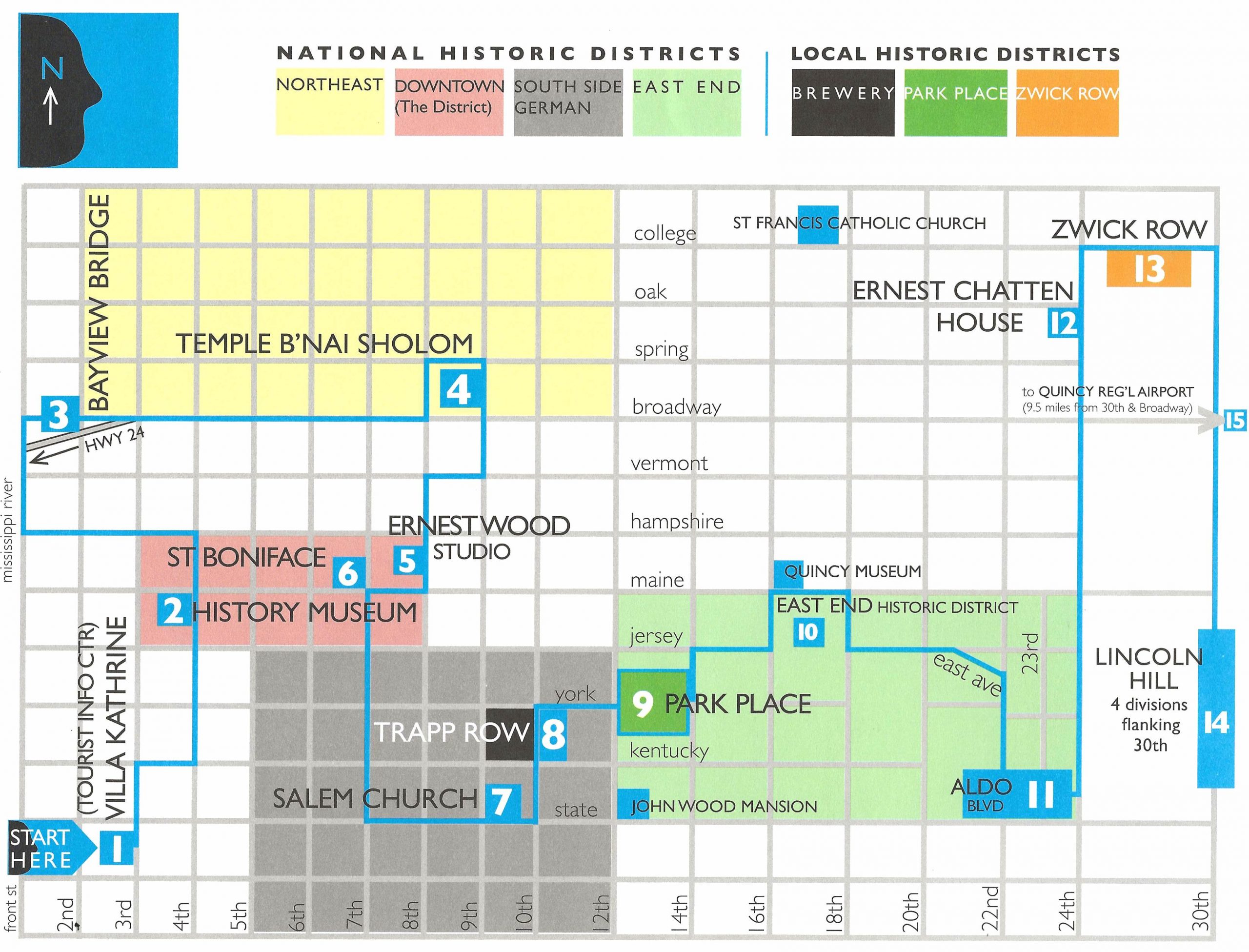

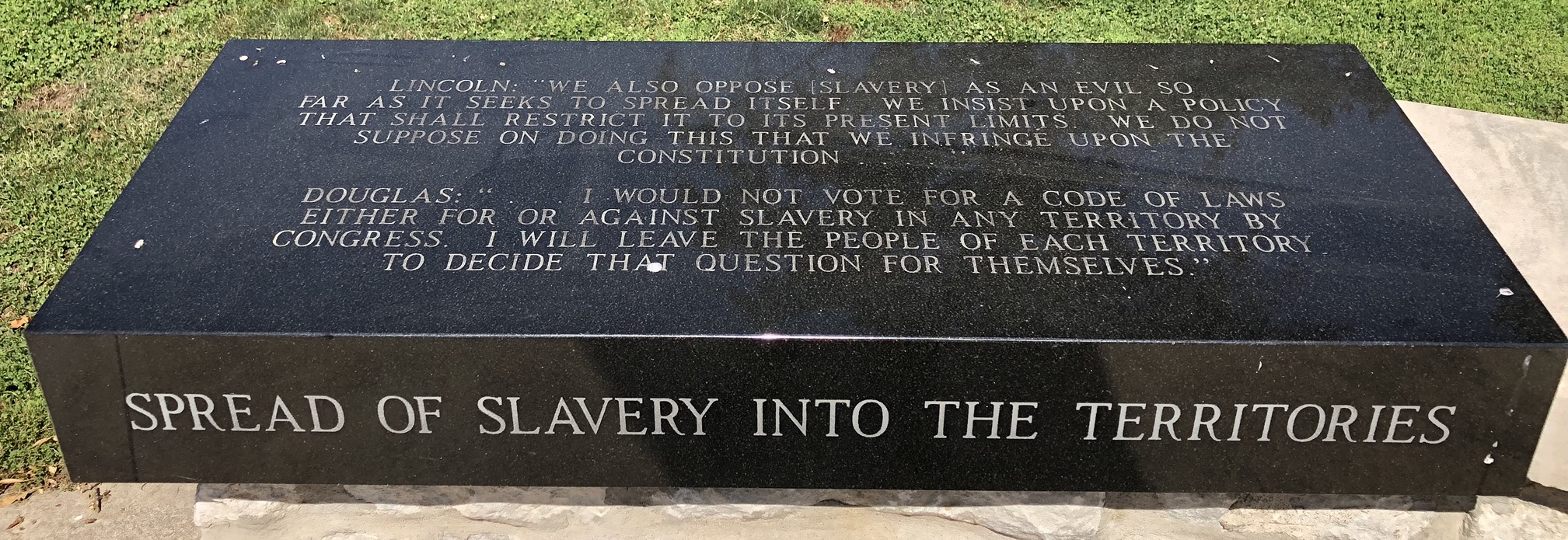

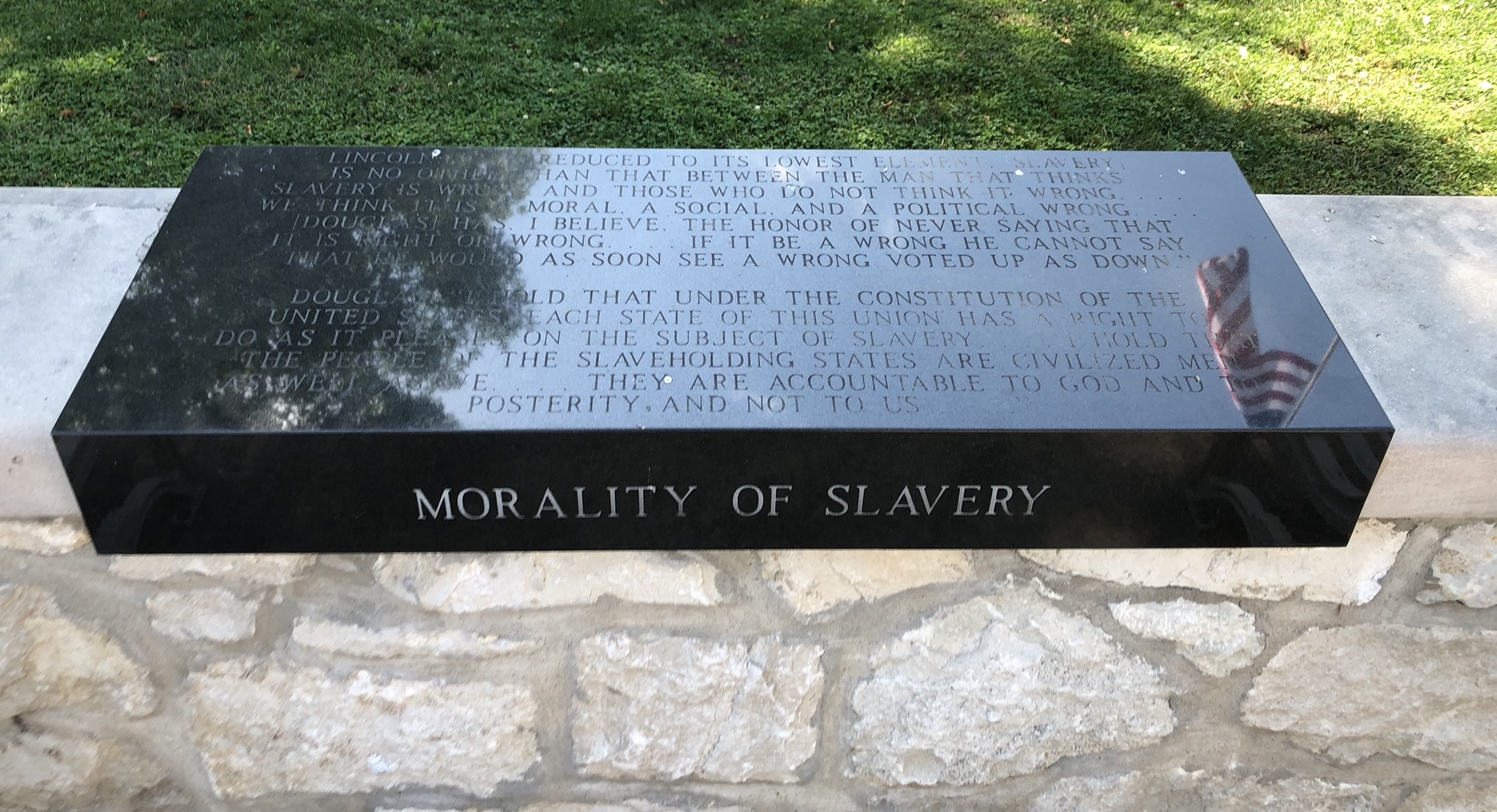

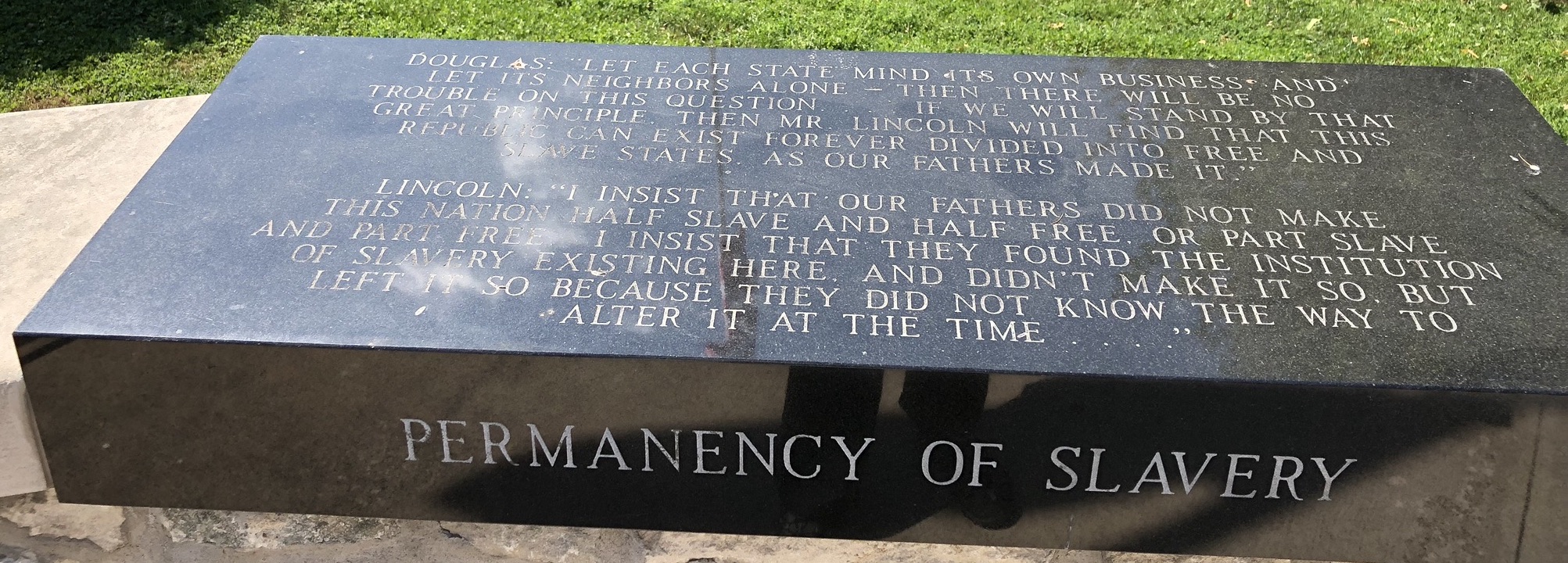

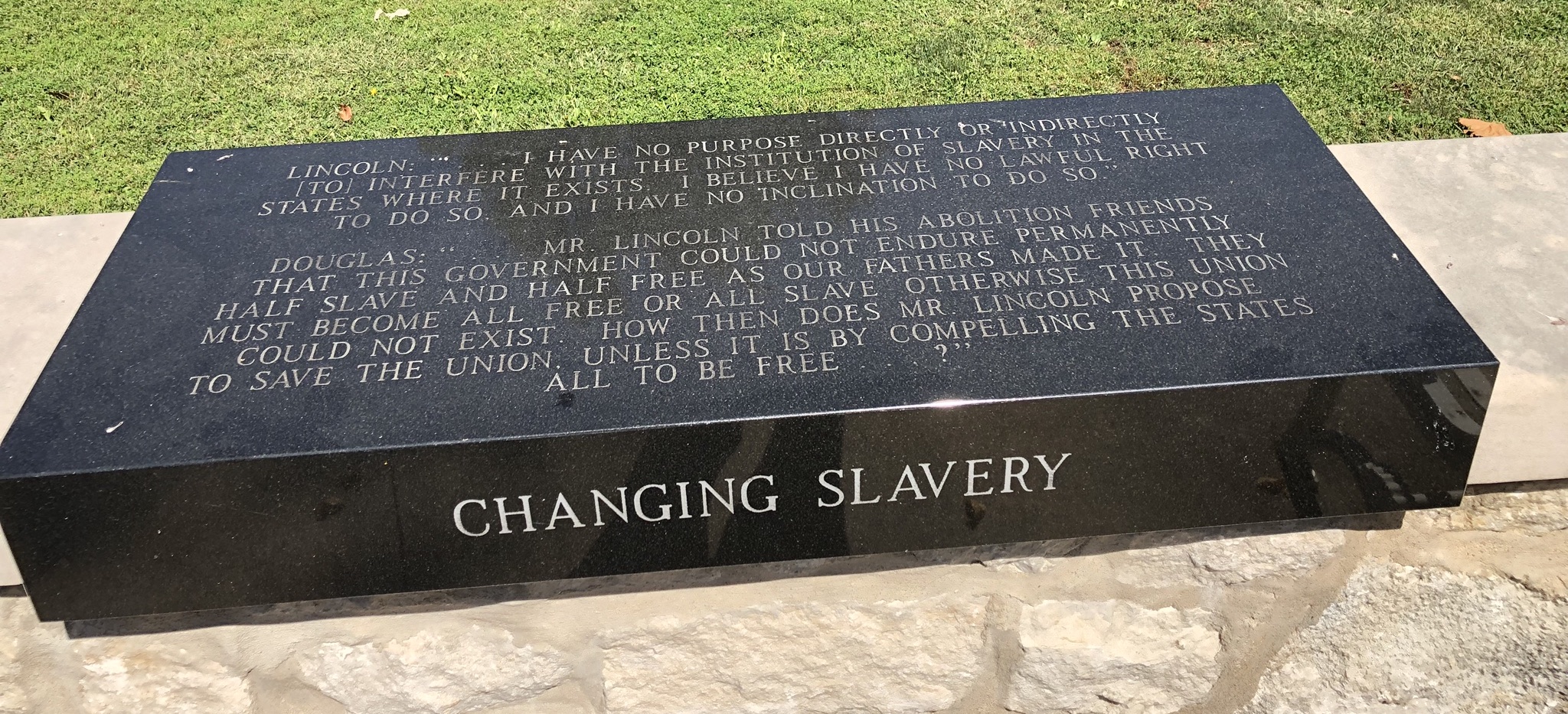

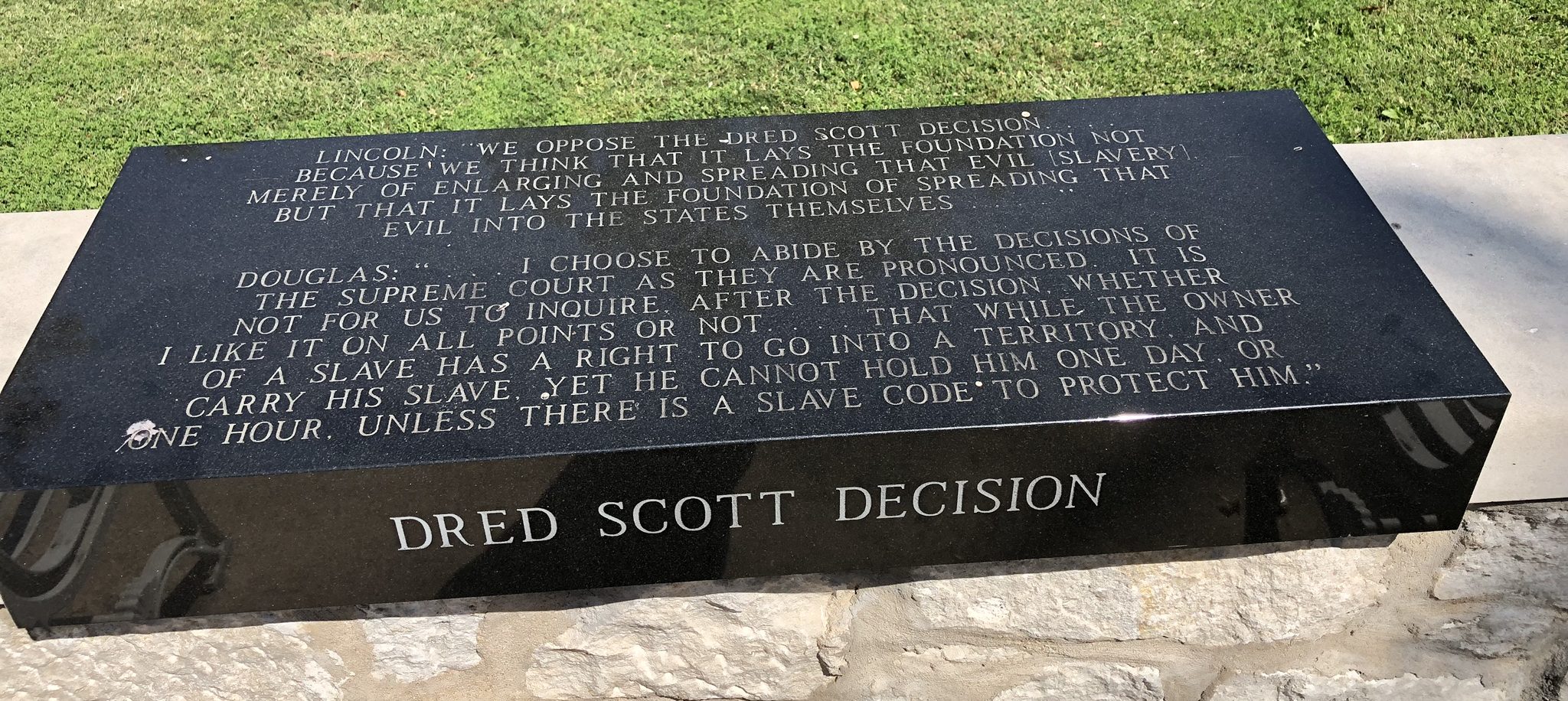

A breathtaking monument commemorating that debate was erected in Quincy’s town square. It is our project’s belief that this monument ranks with many of the greatest public works of conscience in our country and we contend it has not received the attention it deserves. The monument is an outdoor history lesson to be contemplated by residents as well as visitors. The impact of the words from that day, engraved in shining black granite, cannot be overstated.

Interestingly, the impact we refer to above is the result of a 2008 addition to the original memorial sculpture, created by Lorado Taft in 1936 (his last work). Today the tall (7’10” X 12′ X 12′) pictorial plaque stands in the center of a semi-circle of low limestone walls. Originally this free-standing relief panel was solitary. And put tritely, it was a perfectly appropriate homage to Lincoln. Lincoln stands in the center with his right hand resting on a podium. Stephen Douglas sits crosslegged. Mary Todd Lincoln is in profile, watching her husband.

It is the supplementary arrangement of six pairs of point-counterpoint quotes about slavery from the debate, engraved on sloping black granite blocks draped over the low wall of the two halves of the semi-circle, that give the original memorial its extraordinary character.

Within the semi-circle is a map of the United States as it was in 1858.

The Looking for Lincoln program placed two storyboards to provide larger historical contest. Historians agree that this was the debate that propelled Lincoln onto the national stage.

A new article examining Stephen Douglas’ words and practice in life was published in Illinois Heritage (September-October 2020): “Illinois’ Stephen A. Douglas, Statues and Slavery” by Reg Ankrom.

Distinguished Lincoln historian, Professor Graham Peck at UIS, has produced (with Nathan Peck) a unique and provocative film about the debates in their era, called “Lincoln and Douglas: Touring Illinois in Turbulent Times” (2021). It is embedded his website and is highly recommended: https://www.civilwarprof.com/films

In addition, Quincy was an important stop on the Underground Railroad. The Mission Institute #1 (founded by Rev. Dr. David Nelson) (north of today’s Madison Park) was founded in 1836 and harbored slaves. Abolitionist Dr. Richard Eells’ home also was a stop on the Underground Railroad, en route to Chicago. Indeed, in 1843 Dr. Eells was convicted of sheltering a slave – the judge was Stephen Douglas.

Quincy: German immigration

The story of German immigration to Quincy repeats the German story elsewhere in the state: mostly migrants leaving Germany in the 1840s as a result of political issues there (although the first German immigrant arrived in 1829; the first family arrived in 1833). The Germans who arrived in Quincy mostly settled near each other in the southern part of the city (grey area in map above). They influenced Quincy’s architecture and their neighborhood today is called the South Side German Historic District (in its time it was called “Calftown” because so many residents had cows in the yards). Especially characteristic are sturdy brick cottages and ornate fixtures. Quincy had German restaurants, three German-language newspapers, German churches, German schools and numerous German-owned businesses. As would be expected, the German community established breweries. More than half of Quincy’s population has German ancestry. Intangible heritage is kept alive, for instance, with Oktoberfest and Germanfest.

Quincy: exceptional architectural heritage

As one of Illinois’ oldest cities, Quincy has a rich array of historic American architecture. (For an excellent discussion and illustration, see Historic Quincy Architecture, by Richard Payne. Herring Press, 1996) In 2007, the Illinois state chapter of the American Institute of Architects recognized the John Wood Mansion as one of the state’s most important buildings during its sesquicentennial celebration. With its colossal tetrastyle portico, it is a masterpiece of Greek Revival architecture.

There are many early 19th century buildings throughout Quincy. Large Italianate houses can be found all along the neighborhoods adjoining the downtown.

After the Civil War, several notable Richardson Romanesque style buildings were built in its main square, most notably the State Savings and Loan Building and the Quincy Library, now the Adams County Historical Society.